The Laskari dialect was profoundly eclectic in its influences, as befits a language that was used by such a richly varied assortment of people. Consider the names for its ranks: ‘serang’, the seniormost, is thought to be derived from Malay; the next, ‘tindal’ from Malayalam;

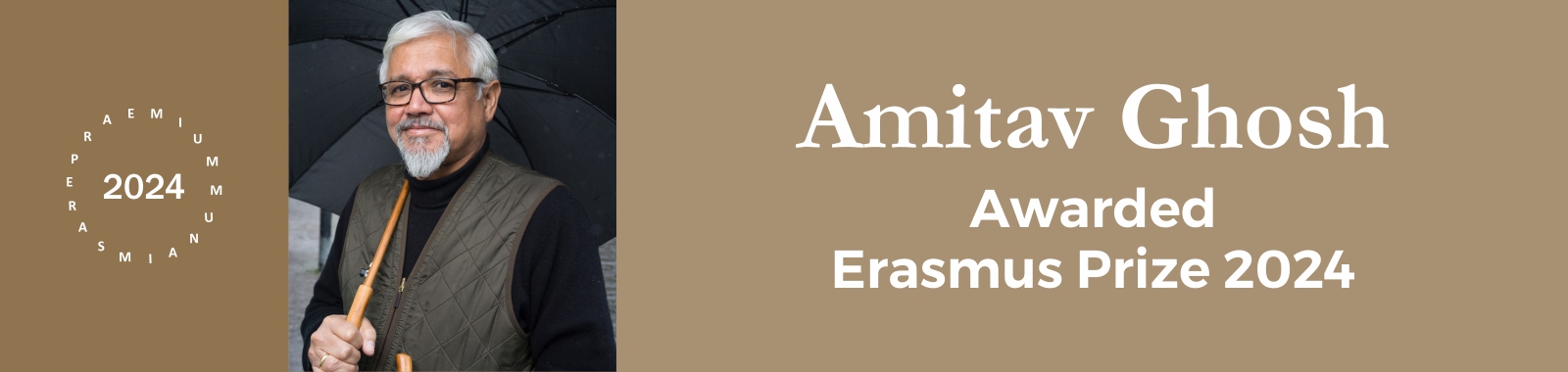

British India Steam Navigation Co Lted (http://www.merchantnavyofficers.com/peterR.html)

the word for helmsman, ‘sukkânî’ (rendered in English as ‘seacunny’) comes from the Arabic for rudder (sukkân);

the word for steward, ‘ishtor’, was an obvious adaptation of the English; ‘kussab’, a lower rank, may have come from Persian; and no one seems to know the derivation of the word for ‘sweeper’ – ‘topas/topaz’. One of the most interesting of these words does not actually find a place in Roebuck’s dictionary: it is the word ‘arkati’ meaning ‘pilot’, which is thought to be derived from the state of Arcot, near Madras, the Nawab of which once had in his employ all the pilots in the Bay of Bengal.[i] The Laskari word for ‘Mate’ – and officers generally – is ‘Malum’, from the Arabic ‘Mu’allim’, or ‘knowledgeable’. But how were the First and Second Mates distinguished from each other: were they Burra and Chhota, or Pehla and Doosra? Roebuck provides us with no clue.

Directional words are possibly the most frequently terms on a ship, and the most basic of these are ‘for’ard’ and ‘aft’. The Laskari equivalents of these, according to Roebuck, were ‘âgil’ and ‘pîchhil’. To anyone familiar with Hindi/Urdu these would appear to be mishearings of the words ‘âgey’ and ‘pîchhey’. But no: Roebuck assures us that this is how the words were pronounced by Lascars and he was certainly in a position to know. Two other directional terms, starboard and larboard, became in Laskari, ‘jamnâ burdu’ and ‘dâwâ burdu’ or, simply ‘jamna’ and ‘dawa’.

Anyone who has spent any time with sailors and boatmen in Asia, will know that they do not conceive of their vessels as inanimate objects: from Roebuck’s dictionary it would seem lascars, similarly, figured their vessels as living things. The most striking example of this is the Laskari word for the kamra known as the fo’c’sle. The English word comes, as the spelling indicates, from ‘fore-castle’ and dates back to a time when there was indeed a castellated fortification at the head of every ship. But in time the word came to refer to the farthest forward of all the vessel’s kamras, which consisted of a shallow, curved space between the bows. Being right above the taliyamar, this was the dampest, most uncomfortable part of the ship, and so naturally it was where the lowliest seamen were lodged. To be a fo’c’sleman, in English, meant much the same thing as shipping out ‘before the mast’ – it was to be a scrub, a Jack, a Tar, a Lascar. But the Laskari language, through an odd conceit, lends this crowded, cramped, foul-smelling kamra a small touch of poetry. The lascars’ word for it was ‘faná’, or hood, as in the flared head of a cobra – and of course, if a ship were to be thought of as a creature of the sea, then this would be exactly the part of its anatomy to which the location of the faná would correspond.

(http://www.aseanindia.com/crews-blog/2012/09/17/super-16-who-climbed-the-mast-during-flag-off)

Similarly, the word for the yard – the spar from which a sail hangs – is ‘purwan’. Roebuck writes of this: “Purwan, I think is compounded of Pur a wing, or feather, and Wan, a ship, which last word is much used by the lascars from Durat (properly Soorut) etc. so that Purwan, the yards of the ship, might also be translated the wings upon which the ship flies”.

[i] Cf. Albert Barrère, & Charles Leland: Dictionary of Slang , Jargon & Cant, Ballantyne Press, 1889.