This month I am participating in an event called Incroci di Civiltà in Venice, along with many other writers including Adonis, Bi Feiyu, Stephen Greenblatt, Gabriella Kuruvilla, Edmund de Waal, Yasemin Amdereli, Michael Ondaatje and Linda Spalding.

Pia Masiero is the Director of the event, which is supported by Venice’s Università Ca’Foscari.

Shaul Bassi, who is a professor in the Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultures in the Università Ca’Foscari, is on the committee that runs Incroci di Civiltà. This is how he describes the event: Incroci di Civiltà is a literary festival promoted by the City of Venice and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice since 2008. Like crossing, the Italian word incrocio means simultaneously intersection, crossroads and crossbreeding. Venice has been for centuries a city where different civilizations come into contact and a place where people and cultures transform each other, offering a model of cosmopolitan coexistence. This event is the felicitous intersection between a university where over forty languages are taught, and a municipality committed the highest international standards in culture and hospitality. Filling a gap left in a city where all the major arts had an internationally renowned event except literature, Incroci has proven itself as a place for the study and comparison of different languages and cultures, attracting over 100 writers from all continents so far.

My event, which is scheduled for April 13, will be an on-stage interview with Anna Nadotti, who has been my Italian translator for twenty-five years.

This is a picture of Anna Nadotti (right) with her friend Marina Forti, who has covered the Indian subcontinent for decades as a journalist. Marina’s book Il cuore di tenebra dell’India: inferno sotto il miracolo (India’s Heart of Darkness: the Inferno behind the Miracle) has just been published in Italy. I am told that it is about mining in central and eastern India, and the economic, political and ecological problems that have resulted from it. I hope it will soon be translated and published in India.

Recently Anna received a letter from a readers’ group in Venice called Circolo ARCI Franca Trentin Baratto. The members of the group are all women and for the last few weeks they have been ‘traveling between Egypt and India’ by reading Lo schiavo del manoscritto (In an Antique Land). They read 50 pages each week and hold weekly meetings to discuss the issues in the book.

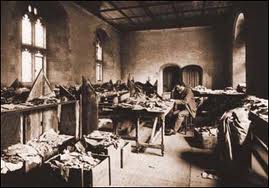

Marina Scalori, a member of the group, sent Anna a beautiful photograph of (I think) Solomon Schecter working on the Geniza archive; and this note, which Anna was kind enough to translate for me.

«Lo schiavo del manoscritto is a rich and gripping travel» we read on The Times. But our first thought, beginning our trip, was, What an impressive amount of notes! What kind of book is it? An anthropological essay or a novel? The notes seemed at the beginning an insourmountable problem. What were we supposed to do? reading note after note according to the indications in the pages? reading them all at the end of each chapter? Not reading them…?

But almost immediately it was the accuracy of the notes themselves that gave us the certitude of the soundness of the sources of Ghosh’s book. A look is enough to realize they provide details and descriptions indispensable for our trip.

See n.8 of the Prologue: we learned merchants exchanged any kind of informations and were the explorers of the world. An explanation as a brush stroke giving us a precious insight on Abrahan Ben Yiju, who lived in Mangalore around 1150 (half XIIth century).

See n.10 of the chapter Lataifa: brick and straw as a deep link between human beings, everywhere in the world – ancient Egypt or Latin America – houses and villages and towns were built with adobe, from the arabic al-tub. In the old times and still today. Adobe as a link of many stories, small and great, private and collective stories.

It’s behind adobe walls that we find the Geniza of Cairo synagogue, where 1000 years old documents were kept, as it was forbidden to destroy even a small fragment of paper where God’s name was written. Thanks to that forbiddance the writer could find and investigate, and we can read Ben Yiju’s and his slave’s story.

Just fragments, a window on everyday life. «Due vasi di zucchero, un vaso di mandorle e due di uvetta, in tutto cinque vasi» or when the misadventures of an old iron pan are narrated. Then our slave appears, to receive «moltissimi ringraziamenti». Just a thank and a name, but from an age where only artists and men of power seemed to have a right to existence, a right to find a place in history. The slave wasn’t parte of such a company, «nel suo caso fu un puro accidente se si sono conservate le tracce appena distinguibili che lascia la gente comune. E’ un vero miracolo che ci sia rimasto qualcosa di lui».

So we go on reading with great pleasure, taken by the narration rhythm, where words really are «musica di fondo»: «Partii dal Cairo in una giornata gelida, dal cielo intessuto di nubi pendevano veli sottili di pioggia».

Then hints to crucial events, when in the XIXth the Cairo Geniza with its heritage of stories, «fili intrecciati lungo i bordi di un gigantesco arazzo», was pillaged and scattered in private and public collections. It was a removing, a clearing away of the multeplicity of history. Something that was going to be repeated.

And simultaneously we are in Lataifa and Nashawy, two Egyptian villages, early 1980s. Fellaheen’s daily life, and we readers as witnesses of the very beginning of vicissitudes bound to become a burden for the present days, for us all.

Here we are, readers/travellers indulging in the pure pleasure of narration. Next meeting, we’ll try to discover the deep ties between past and present, and to go on in the unveiling of our slave and Ben Yiju.

The Italian title of In An Antique Land – Lo schiavo del manoscritto (literally ‘The Slave of the Manuscript‘) – has a special resonance in Venice, for this city has played an important part in the etymological history of the word ‘slave’ (schiavo in Italian; esclave in French). All these words derive from the Latin Sclavus, the original meaning of which is ‘Slav’ as in ‘the Slavic peoples’. The derivation of the word is thought to date back to the reign of Otto the Great (912-973 C.E.), the founder of the Holy Roman Empire, during whose reign great numbers of Slavs were taken captive.

The Venetian Empire played an important part in the circulation of slaves in the Middle Ages. Its fleets transported thousands of Slavic captives from the ports of the Black Sea to Venice. From there they were sent on, not just to Europe, but also to Africa and the Middle East.

This history is commemorated in the name of one of the most celebrated landmarks in Venice, the Riva degli Schiavoni (‘Quay of the Slavs/Slaves’) – depicted here in a famous painting by Canaletto:

And in this photograph taken a couple of days ago.

And in Veneto region, words deriving from schiavo are quite common surname, I have always felt a little shy of asking the details of such surnames, feeling that may be the families were in slave trade. But like you point out, it could mean that families were of slavic origin!

I hope that I can come to listen to you on 13th, just need to juggle an appointment! 🙂

Amitav: We’ve lost touch. It’s lovely to see you about to go to Incroci in Venezia, hosted by my dear friend Shaul Bassi. I hope we can cross paths soon again.

All best,

Louise

Thanks Louise – I too hope that we will meet soon.

best

Amitav

I wish they had put your part in this event earlier in the day. Last train from Venice for Bologna is around 7.45 PM, and coming to Venice by car is such a hassel.

If by chance you pass through Bologna, I will be happy to be your guide and show you my favourite places in the city! 🙂