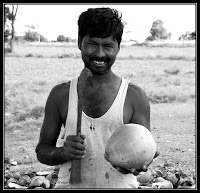

No garment lies closer to the heart of the Indian male than the banyan.¶ Yet, despite its hundreds of millions of adherents, the ubiquitous undervestment of the subcontinent gets little attention and even less respect:

designers scorn it; dudes despise it; its mere outline, were it to be glimpsed, would bring ruin upon an aspiring male model.

I confess that I, like most Indian men, am deeply attached to the humble banyan: like many of my fellow-devotees, I have never been able to rid myself of the illusion, fostered in earliest childhood, that my banyan provides a necessary layer of insulation without which my shirt would not be dry and my chest would be defenceless against all the germs, viruses and malign humours that seek to invade it.

But reason alone cannot explain the addict’s attachment to this garment. For a true devotee the banyan is much more than a mere article of clothing: at the deepest level it is a marker of identity, a link with the past.

This is why it annoys me when marketers attempt to rebrand the banyan as a ‘sleeveless undershirt’, ‘singlet’ or ‘vest’. To call it anything other than a banyan is to demean and disparage a garment that has every right to be proud of its distinctive name and lineage.

The destiny of a word can sometimes hinge on a tiny shift of emphasis. Notice how the word banyan, when it refers to a humble article of clothing, is pronounced with the stress on the last syllable – banyán. Move the emphasis to the first syllable – bányan (as in banyan-tree) – and we have a word that is infused with spiritualism and freighted with overtones of ecological benevolence: a word so eminently fashionable in fact, that hundreds of thousands of products, from soaps to spas and restaurants, have incorporated it into their brand-names.

Indeed it may well be one of the most popular brand-names in existence – a brief googling produces over four million entries.

The words bányan and banyán may appear to be as unlike in their fortunes as prince and pauper, but they are actually twins and share exactly the same parentage: both are derived from the name of a caste – the ‘vania’ or ‘bania’ merchant community.

The transition from ‘bania’ to ‘banyan’ began some eight or nine hundred years ago, the process being set in motion by Arab and Persian travelers and scholars, some of whom used the word baniyân as a generic term for Hindu merchants (the final consonant ‘n’ was probably added to indicate a collective noun).

While writing In An Antique Land I frequently came across the word baniyân in Arabic geographical texts. Abraham Ben Yiju, the 12th century merchant from North Africa whose letters provide much of the material for the book, had close connections with the merchant communities of the Malabar coast. He refers on at least one occasion to the ‘baniyân Manjalûr’ (‘banias of Mangalore’). §

When Europeans arrived in the Indian Ocean, they adopted the Perso-Arabic usage, and ‘banyan’ became a general term for things associated with India: the banyan-tree is thus merely the ‘Indian tree’. In matters of costume similarly, the word ‘banyan’ probably once referred to an item of clothing that was distinctive of India. This may have been an ancestor of a vest like those that Mahatma Gandhi used to wear – but it is hard to know for sure, because nothing could be more unlike the Mahatma’s simple angarkho than the earliest surviving examples of the garment that went by the name ‘banyan’.

Several of these, dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries, are on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London:

they are sumptuous, heavily-embroidered ankle-length robes that look like ornate dressing-gowns. They were typically worn by nabobs – that is to say, Britons who had made their fortunes in India.

These two (from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Website) are described as having been made on the Coromandel Coast, India, between 1750-177.

The accompanying legend says: ‘The loosely cut style of this banyan (a man’s informal robe) is based on that of the Japanese kimono, although the word itself is derived from the Indian word, banya, for a merchant or trader. Robes like this became popular in England and Holland from the mid-17th century, and were often made up of imported Indian chintz fabric, as in this case. Banyans could also be made of Chinese, or sometimes French, silk. Their generically ‘oriental’ air was part of a wider taste for exotic designs that formed part of the Chinoiserie style.’

The fabric was painted and dyed cotton chintz

and the garment was lined with block printed cotton.

__________________________________________________

¶ A version of this was published in 2009 by Vogue India under the title: ‘Confessions of a Banyan Addict

§ Taylor-Schechter Manuscripts, Cambridge University Library, N.S. J 1, verso, line 14.

Interesting post as usual. Any idea about the word “Ganjee” as the Baniyan is (still) called in Bengal and interiors of Hindi heartland as well?