I met Layli Uddin in London, in the British Library.

She is of Bangladeshi origin and grew up in England. She has an MPhil in Modern South Asian Studies from Oxford and has also studied at the London School of Economics and Harvard. She is now a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London. The title of her thesis is: Mobilising Muslim Subalterns: Bhashani and the political mobilisation of peasantry and lower urban classes, c.1947-71.

Layli will soon be traveling to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh in search of new sources and information on Maulana Bhashani.

This is how she describes her work:

Thus far, much of the academic work on East Pakistan and events leading up to the war of 1971 reflects an elite bias, with its overwhelming focus on the role of Dhaka and the urban intelligentsia. My work argues though that it is the active and forceful participation of the ‘subaltern’ i.e., the peasantry and lower urban classes in various protests, starting from the language protest in the 1950s through to the industrial and rural ‘gherao’ protests in the 1960s and the freedom movement of the 1970s which transformed the nature and dynamism of these resistances and presented a real threat to the a governing authority in West Pakistan. It therefore thrusts, and rather deliberately too, the neglected and marginalised subaltern in the limelight and looks at how they envisaged this ‘land of eternal Eid’ and why that rather Arcadian paradise soon disintegrated into a land stalked by angry and disenchanted peasants and lower urban classes. I look at the different forms and practices of subaltern resistance and attempt to excavate the consciousness of the peasant through the official records as well as other mediums such as folk songs, rhymes, ballads, anecdotes and literature of that period.

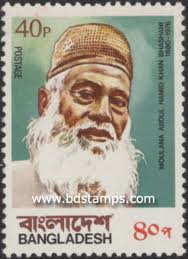

Maulana Bhashani plays a central figure in my work on restoring the creative agency of the ‘subaltern’ in the making and unmaking of Pakistan between 1947-71. Maulana Bhashani, who had made his mark as an unusually powerful pir, radical peasant leader and politician in colonial Assam went onto become one of the main dissenting figures to the rule of West Pakistan authority. American officials described him as ‘East Pakistan rabble rouser par excellence’, the Jamaat-e-Islami as ‘kaafir’ and the East Bengalis as ‘Majlum Jononeta’ (leader of the oppressed). My work seeks to understand the charismatic authority of Maulana Bhashani and his relationship with the peasantry and lower urban classes in East Pakistan. It is a charisma that befuddled many; the US Consul General, Archer Blood, when paying a visit to Bhashani was left bemused by the popularity of the bare-footed 88 year-old man, clad in a dirty undershirt and lungi who greeted him. My work looks at Bhashani’s network and spheres of influence, ideas on Islamic socialism and his strategies of political mobilisation.

It is difficult to summarise the enigma that is Maulana Bhashani and what a complex and exciting figure he presents for research – how did this Deobandi-trained maulana come to defend Tagore’s music and become the leader of Marxist revolutionaries in East Pakistan? Why did the founding father, Mujib, fear being upstaged by the septaguenarian Bhashani? How did Bhashani’s Islamic socialism ‘fit’ with the radical demands made by peasantry and lower urban classes in East Pakistan? My work has already thrown up some fascinating and tantalising information, which I hope to explore as research progresses – Bhashani’s relationship with radical ‘ulama in colonial India; his meetings and encounters with the grandees of the political left in Europe such as Attlee, Bevan, Bertrand Russell, Neruda, Hikmet and Ehrenburg in Europe and his other trips to Egypt, Cuba and China in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Admittedly, as a first year PhD student, this is all striking me as rather too ambitious, with perhaps all the pretensions of a Howard Zinn impostor, but nonetheless exciting, foray into a rather neglected yet critical part of Bangladeshi history.

My conversation with Layli got off to a good start because it so happens that I have actually met Maulana Bhashani. It happened when I was very young and I have no memory of the meeting: I know of it only because my father liked to tell the story. Apparently, when I was a little boy, the Maulana saw me at a gathering, somewhere in Dhaka, and hoisted me on his shoulder.

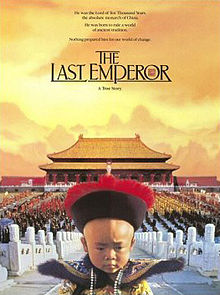

When I recounted this to Layli she was not at all surprised. Maulana Bhashani had many unlikely encounters, she said – including one with Pu Yi, the last Emperor of China.

My mouth fell open.

The Last Emperor and Maulana Bhashani? Had they really met? How could she possibly know?

Through the Maulana’s account of it, said Layli.

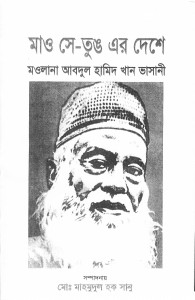

He had written about the encounter in his book, Mao-Tse Tung-er Deshe (In Mao Tse-tung’s Country, by Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani).

Quite apart from the inherent interest of a meeting between the last incumbent of the Qing dynasty and this leftist-Deobandi Maulana, I was also taken by the sudden shrinkage in the degrees of separation between myself and the last Emperor of China. I asked Layli if I could read the chapter and she was kind enough to provide me with a copy.

I was not disappointed: the Maulana’s account of the meeting is strangely compelling, and since it has never been published in English I decided to translate a few excerpts myself. These will appear on this site as a multi-part series.

From Mao-Tse Tung-er Deshe by Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, p. 42

I am on my way to meet the last monarch of the mighty Manchu empire: the last emperor of the Qing dynasty, Pu Yi. For 250 years the Qing dynasty ruled and misruled China; it was they who opened China’s doors for foreign looters …

Pu Yi conspired against the people of China with Japanese and Western imperialists. And now the same Pu Yi has committed himself to the building of a socialist society. What sort of man is this Pu Yi?

…At one time Pu Yi was training to be a curator in a Chinese botanical garden. But in 1961 a commission was specially created to write a new history of China and he was transferred to an office of the People’s Consultative Conference to help with the research. That was where I met Pu Yi. He is a slim, inoffensive-looking man of middling stature. I couldn’t find any resemblance between him and the Pu Yi of my imagination. His bright, smiling face and his shining eyes betrayed no signs of the sly conspirator. I was amazed – could this be the same Pu Yi who helped the Japanese against Chinese revolutionaries? Who wanted to keep China prone while he floated high on the froth of luxury? I could not quite believe it. How old could he be? Thirty, or at the most thirty-five? But Pu Yi corrected me himself, saying that he was actually 57 years old. He looked very young for his age.

I entered his office at four in the afternoon and when I left it was eight thirty.

[to be continued…]

It is seems that there are so many hidden worlds, waiting to be explored. So I am looking forward to reading more about Maulana Bhashani and Pu Yi.

While reading about Maulana, I was thinking that all history books limit themselves to a few persons, usually the few literate and articulate leaders who come from upper classes. However, all revolutions need Maulana like figures to mobilise peasants and masses. Usually history books ignore these figures, except for some exceptions when their power over the masses becomes huge and can’t be ignored – for example, Gandhi ji. What do you think?

You are right. Many very important figures are neglected by history, especially in South Asia. Maulana Bhashani is one of them.

amitav

Fascinating connection; and for me continues your wonderful Ibis trilogy.

Amitava, you have done a great service by bringing the fact that someone is working on Maulana Bhashani. In fact when I had been swayed by the Students’ unrest in world in 1965-67, Maulana Bhashani, the charismatic leader of peasantry in the East Pakistan used to be frequently discussed among friends. One commentator is correct in observing that not much has been done on the leaders in the Bengal. One such character was Suharawardi of the Muslim League who played an all important role in the creation of Pakistan. I wish someone writes on him. When this omission was brought to the information of Ramchand Guha who has written a wonderful book ” India after Gandhi”, he was dismissive but the historical fact was that it was the Unionist Party not Muslim League which was in power in Lahore. On the other hand, the Direct Action Day call of Suharawardi expedited the creation of Pakistan.

Very interesting. Thank you.

Amitav

MR. AMITAV GOSH,

I FOUND YOUR WEB-SITE VERY INTERESTING AND INFORMATIVE. FRANKLY SPEAKING, I ALSO FOUND YOUR ITEMS VERY THOUGHTFUL. I HAVE WRITTEN ON MAULANA ABDUL HAMID KHAN BHASHANI: I SIMPLY THOUGHT LET ME POST IT IN YOUR WEBSITE. IF YOU ARE INTERESTED I CAN POST MORE ARTICLES ON MAULANA BHASHANI.

Since Layli Uddin’s Ph.D.dissertation topic is titled “Mobilising Muslim Subalterns: Bhashani and the Political Mobilisation of Peasantry and Lower Urban Classes, c.1947-71, several of my articles on Bhashani and references may be relevant to her research. A general reader also finds interest in articles or items on Maulana Bhashani. I am wishing the very best in your acedemic pursuits.

With the deepest regards,

M. Waheeduzzaman (Manik)

P.S. Why on Bhashani only? There are other unsung heroes of Bengali nationalism. I am sending you separately one of my article on DHIRENDRANATH DATTA for perusal. W. Zaman Manik

(Reprinted from the FORUM of THE DAILY STAR, January 2012)

MAULANA BHASHANI: THE MAJLOOM JONONETA

by M. Waheeduzzaman Manik

(M. WAHEEDUZZAMAN MANIK provides glimpses of the formative phase of the life and struggle of Maulana Bhashani)

Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani was aptly called “Majloom Jononeta” (leader of the oppressed) because of his uncompromising commitment to the needs of the poor, landless, peasants, workers, sharecroppers, abandoned, exploited and repressed people of the society. By any measure, his long political struggle was characterised by his selfless dedication for championing the causes of the most underprivileged segments of our society. Throughout almost six decades of a struggling political life, Maulana Bhashani was both a demanding spirit and a fearless voice for emancipation of the humblest, exploited, terrorised, and oppressed citizens against the overwhelming powers of the governmental machinery and the overweening grip of the ruling elite of the society. Indeed, he had to his credit an unblemished and impeccable record of life-long relentless struggle for the downtrodden, the poor, the vulnerable, the neglected, the deserted and the disinherited. Yet his dignified comportment throughout his eventful political struggle had displayed a quintessential bravery, relentlessness and dauntlessness

However, Maulana Bhashani was more than a defender of the peasantry and working class. He was responsible for building up an epoch-making resistance movement against the infamous Line system and the brutish Bangal Kheda movement in colonial Assam. He was both the maker and shaker of political events during the most turbulent years of the then East Pakistan. The seed of politics of opposition and agitation was carefully planted by Maulana Bhashani in the formative years of Pakistan in an era when the overwhelming majority of Muslim population of the then East Bengal was not yet ready to be disillusioned with the euphoria of Pakistan movement. He had played a defining role in the difficult task of building up East Pakistan Awami Muslim League, a viable opposition party in the then Pakistan. Doubtless, his was the fearless dissenting voice in the formative years of Pakistan. He was an active leader of the Bengali language movement. He was one of the chief organisers of the United Front, an electoral alliance that routed the ruling Muslim League party in the 1954 elections. He was not only the authentic founder of the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League (EPAML) but he was also the founder of the National Awami Party (NAP). Therefore, the appearance of Maulana Bhashani in the regressive political scenario of the then East Bengal as the most dauntless dissenting voice and an effective organiser of a sustainable opposition party that was capable of building-up a viable resistance movement against the Punjabi-Mohajir dominated Karachi-anchored Pakistani ruling elite was nothing short of a miracle.

It is part of Bangladesh’s robust political history that it was Maulana Bhashani who had organised the historic anti-Ayub movement which took place in late 1968 and early 1969 that prompted and hastened the withdrawal of the infamous Agartala Conspiracy case and the unconditional release of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman from captivity. It is widely acknowledged that he had orchestrated a series of ‘gherao’ (a form of non-violent sit-in strikes designed to ‘encircle’ the governmental official against whom a protest was directed) immediately before and during the 1969 student-mass movement eventually led to the shameful downfall of the dictatorial regime of Ayub Khan. Maulana Bhashani’s legendary name is also integral part and parcel of Bangladesh’s struggle for freedom and independence.

Although Maulana Bhashani was intimately associated with all of the progressive movements during the Pakistan era from 1947 to 1971, no attempt has been made to provide any analysis or chronological details of any of those movements within the limited scope of this article. No effort has been made to discuss his fearless role in building-up the EPAML as a viable opposition political party in the then East Pakistan. Rather, the main purpose of this piece is to reflect on the formative phase of Maulana Bhashani’s life and political struggle with specific reference to his struggling life up to late 1920s and early 1930s when he made Assam’s Brahmaputra valley his place of residence and political struggle. However, a detailed discussion of strategies and tactics of his anti-Line system and anti-Bangal Kheda movement is not possible within the size of this paper.

Gleanings from his early life

Maulana Bhashani was born in 1885 (circa 1884) at a village named Dhangora within the jurisdiction of Sirajganj subdivision (at present Sirajganj is a district) of the then Pabna district. He was the second son of Alhaj Mohammad Sharafat Ali Khan and Mosammat Majiran Bibi. His father was neither a Zamindar nor a Talukder. Nor was he a Jotedar (intermediary between landlord and peasant) of any kind. Mohammad Sharafat Ali Khan owned a small grocery shop. He also owned a couple of acres of cultivable land. Although he was at best a middle-range farmer when Maulana Bhashani was born, his family status was quite respectable in his village by economic standards of that time. It is believed that he was a religious man who had performed Haj at an early age. According to some accounts, he performed Haj at the age of 35, and it is believed that he had walked from Mecca to Medina barefoot through the desert. The Haji title in those days added prestige not only to the performer of Haj but also added a new status to the family of a Haji.

Alhaj Mohammad Sharafat Ali Khan had named his second son Abdul Hamid Khan. However, Maulana Bhashani was known as Chega Mia during the early phase of his life. From whatever is known about his father and mother, it is plausible to suggest that his father and mother were caring parents. Unfortunately, Chega Mia lost both of his parents when he needed them most. He was hardly five or six years old when his father died at an early age in 1889 leaving behind his wife and young children (three sons and a daughter). Chega Mia (Maulana Bhashani) also lost his grandparents, mother, two brothers, and a sister in an epidemic (cholera) in mid-1890s (most probably in 1894 or in 1895) when he was barely 10 years old. Since he lost both of his parents and his grandfather at a very early phase of his life, he had to journey through a chequered boyhood. Given the fact that his father’s untimely demise preceded his grandfather’s death, Maulana Bhashani was clearly deprived of his inheritance right to his father’s property. He was a student at a junior madrasa for several years but he could not continue his studies due to abject poverty and changed pecuniary circumstance. As a madrasa drop-out, he had no shelter even at his paternal house due to the betrayal of his close relatives. He came to know what hunger and starvation meant as a young boy because he had neither food nor lodge even though his father left behind homestead and cultivable land. So he had started wandering around for several years, and there was no profession left in which he did not try his luck in those trying days.

The orphan son of a mid-range Muslim farmer cum petty grocer and a grandson of a humble peasant, Maulana Bhashani had little reason to anticipate, in those trying times, a dedicated and selfless life of an ardent defender of the oppressed and downtrodden people. As a young disciple of Pir Syed Nasiruddin Shah Baghdadi, he had visited and stayed in Assam in the early years of 1900s (his first visit to Assam is believed to be in 1904). Although his main task in those days was to take care of various household chores of Pir Nasiruddin Baghdadi, Maulana Bhashani had received his basic Islamic education including his skills in the rudiments of Arabic from his association with Pir Syed Nasiruddin Shah Baghdadi. At the behest of this Pir, he had also the rare opportunity to pursue more formal religious education at Deobond Madrasa for almost two years. During his stay at Deobond in 1907-09, he was deeply influenced by Maulana Mahmudul Hasan who was popularly known as ‘Shaikhul Hind’. It is being conjectured by most of the biographers of Maulana Bhashani that the progressive Islamic thinkers at Deobond and the liberal traditions of Sufi Islamic preachers might have immensely inspired him to become a fearless fighter against all types of oppression and exploitation including his steep opposition to the perpetuation of British imperialism.

After his return from Deobond, most probably at the end of 1909, Maulana Bhashani started teaching in a primary school which was located at village Kagmari near Tangail town at a monthly remuneration of no more than three rupees. He also taught in a madrasa at village Kala near Haluaghat in Mymensingh district after he had quit his primary school job. Since he used to earn a monthly pittance in both of these places, his pecuniary circumstance had remained sluggish in those days. However, it is fair to suggest that wherever he went to work or live in those almost forgotten years he had demonstrated a knack for getting himself involved with the problems of the common people of that area. For instance, he used to deal with the problems of the poor, the poorest of the poor, the neglected, the hungry, the malnourished and the downtrodden. Maulana Bhashani had a strong desire for motivating and organising the marginal peasants and vulnerable villagers to resist all forms of injustices.

There is little wonder why the targets of his grass root level resistance and protest movements in those days were the Zamindars, Talukders, Jotedars, and Mahajans (money lenders). In fact, the juxtaposition of precarious conditions of the vulnerable tenants vis-à-vis the powerful landed class piqued his interest in the difficult task of defending the peasants, sharecroppers and landless agricultural laborers. If there was a conflict between a tenant (a ‘Proja’) and a feudal landlord, Maulana Bhashani was always on the side of the tenant. He was not only an ardent defender of the tenants’ rights but he was one of the most dedicated and effective organisers of the ‘Proja’ movement in early 1920s. (Details on the early phase of Maulana Bhashani’s life can be gleaned from Chapter I of Syed Abul Maqsud’s seminal work titled Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Bangla Academy, 1994, and Peter Custers’ “Maulana Bhashani and the Transition to Secular Politics in East Bengal,” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Vol. XLVII (47), No. 2, April-June, 2010).

Glimpses of the formative phase of his political struggle

Given the fact that the formative phase of Maulana Bhashani’s political struggle is a matter of distant past, it is difficult to ascertain the exact day or month or even the year when he got formally inducted into national or regional politics. He had developed both the compassion and organisational experience before he made his debut in national politics after joining the Indian National Congress in 1917. Although there is a paucity of authoritative details of the nature of his involvement in national politics of that time, there is no doubt that Maulana Bhashani actively participated in the Non-Cooperation and the Khilafat movement, and he was imprisoned for a brief period during that time. He was a great admirer of Ali Brothers (Maulana Mohammad Ali and Maulana Shawkat Ali) and Deshbandhu Chitta Ranjan Das. Maulana Bhashani had joined the Swarajya party with great a deal of enthusiasm being immensely impressed by Deshbandhu’s charismatic and compassionate leadership style. He worked hard as a grass-root level foot soldier of the short-lived Swarajya party being essentially moved by the magnitude of personal sacrifices of C.R. Das toward achieving sustainable unity between the Hindus and Muslims in Bengal. Like C.R. Das, Maulana Bhashani sincerely believed and worked very hard for forging Hindu-Muslim unity. He was greatly saddened due to the sad and sudden death of C.R. Das on June 25, 1925.

Although Maulana Bhashani got himself involved in national politics in early 1920s, he voluntarily remained chiefly involved in the difficult task of ventilating, articulating and defending the genuine rights of the most vulnerable peasants of the regions wherever he lived in those years. In other words, he preferred to work among the peasants even though he had emerged in national politics before, during and after the Non-Cooperation and Khilafat movements. Maulana Bhashani’s leadership experiences in the peasant movements in greater Mymensingh district and in other northern districts of Bengal had invariably played a role in his emergence as a charismatic peasant leader in Assam. Banned from the then greater Mymensingh district and eventually after being expelled from various northern districts of the then Bengal province, Maulana Bhashani settled in Char Bhasan (Gaghmari) of Assam in 1926 (according to some accounts, he took permanent residence in Assam in 1928).

As noted by Amalendu Guha, “After his first political experience reportedly as a Khilafatist and Non-cooperator, he (Maulana Bhashani) discovered that the real interests of the Muslim peasantry of Bengal lay in a consistent struggle against the zamindars and moneylenders, who were mostly Hindus. He did not hesitate to exploit the religious sentiment to organize and unite the oppressed Muslim peasantry, who constituted the overwhelming bulk of the Bengal peasantry. … The itinerant Maulana, with his simple and pious habits and great organizing abilities, was accepted by the rural folk not only as a political leader but also as a Pir (saint), believed to be possessed of occult power. Hounded out of Bengal by the zamindars and the police, he settled down on the wastelands of Ghagmari, a few miles from Dhubri in Assam, and also set up another establishment in Bhashanir-char (or Bhashan char), an island in the Brahmaputra (river). Both (places) were in Goalpara district where (Bengali) settlers already formed a fifth of the population. It was after the name of the latter place (Bhashan Char) that he was nick-named ‘the Maulana of Bhashani’ or simply ‘Bhashani’ in due course” (Amalendu Guha, “East Bengal Immigrants and Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani in Assam Politics, 1928-’47,” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Volume XIII, No. 4, 1976, p. 426)

Similar views about Maulana Bhashani’s intimacy with the peasant movement during the formative stage of his political struggle have been expressed in a recently published article by Peter Custers, a left leaning European scholar. As emphasised by Peter Custers, “Though Bhashani originally hailed from Shirajganj in East Bengal (now Bangladesh), he derived his appellation “Bhashani” from ‘char’ Bhashan, a low lying area of Assam. It was here, in late (19) twenties, having been forced by the British colonial authorities to seek refuge beyond the borders of Bengal, that Bhashani cleared the jungles to build his own bamboo hut. Already by this time, the fiery theologian had distinguished himself as an opponent of the feudal zamindari system which was the backbone of Britain’s rule over Bengal. The Bengal province in the 1920s had seen the emergence of a movement for tenants’ rights. The ‘proja’ movement, protesting unjust impositions by absentee landlords, was actively supported by many rural intellectuals, including lawyers and Islamic preachers. Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan, later to be known as ‘Bhashani’, was not only an advocate for, but also a key organizer of this movement. In fact, he convened several big peasant gatherings before being compelled to shift his habitation to Assam. In Assam, the Maulana re-emerged as an effective and popular peasant leader, ready to champion the cause of the downtrodden” (Custers, Peter.. “Maulana Bhashani and the Transition to Secular Politics in East Bengal,” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Vol. XLVII (47), No. 2, April-June, 2010, p. 232).

There is no doubt that Maulana Bhashani had become a legendary political figure in Assam in mid-1930s and 1940s. Yet it needs to be underscored that he had Assam connection long before he settled there in later part of 1920s. As a young disciple of Pir Syed Nasiruddin Boghdadi, as noted earlier, he had visited and stayed in Assam in the early years of 1900s. Maulana Bhashani had numerous disciples in Assam even before he permanently migrated there in late 1920s. It is believed that he was a frequent visitor to Brahmaputra valley of Assam in 1920s. He was intimately familiar with the devastating effects of the infamous Line system on the Bengali immigrant peasantry in Assam. He had first-hand knowledge about the deplorable plight of the Bengali Muslim immigrant settlers in Assam before he moved there to live. He also felt the acute need for effectively mobilising and organising the Bengali immigrant settlers throughout the Brahmaputra valley in Assam. In fact, he had realized quite early that his fight against the Line system needs to be backed up by public support and awareness, and his initial efforts were deliberately geared toward garnering such public support. For example, in 1924, Maulana Bhashani had organised a large public meeting of Bengali peasants at “Bhashan Char” (Bhashani Island) of Dubri district. The great success of this mammoth gathering of Bengali migrant settlers in Dubri area had inspired Maulana Bhashani to devote his undivided attention to the task of organising more peasant gatherings and rallies in far flung areas of vast char lands of Brahmaputra valley.

Soon after Maulana Bhashani settled in Assam, he observed that the hardworking Bengali settlers in lower districts of Assam were very vulnerable to all forms of discrimination and exploitation because they were not at all organised to protect their own legitimate rights. It was clear to him that those Bengali immigrant settlers in Assam were not in a position to build up any kind of resistance movement against the government-sponsored discrimination and violence. Although he had never hankered after power or authority, he decided to take that responsibility upon himself to organise and develop a sustainable resistance movement of the immigrant peasants against the overweening powers of the vested interests. Maulana Bhashani’s strategy at the initial stage of his struggle against the Line system was to prepare and mobilise the unorganised and vulnerable Bengali immigrant settlers in Assam. He was not willing to waste even a moment in building up a sustainable movement against the infamous Line system.

There was a total absence of any dedicated leadership committed to further the just causes of the migrant settlers in Assam even though some ‘Bhadralok’ Muslim leaders started showing sympathy for the Muslim immigrants. However, the seasonal or sporadic support or sympathy they had received from the Muslim leaders was at best political posturing before the general elections that were scheduled to be held in Assam in early 1937. Neither the upper class Muslim leaders nor the Bengali-speaking Hindu leaders were the trusted allies of the tormented Bengali Muslim settlers in the Brahmaputra valley. In fact, the educated middle class Bengali speaking people of Assam did not offer any form of tangible support for the legitimate grievances of the Bengali immigrant settlers in Assam. Being apparently disgusted, one Bengali scholar (Amalendu Guha) had characterised the lukewarm support of the Assamese Muslim leaders for the Bengali Muslim immigrant settlers in the Brahmaputra valley as “wordy” and “motivated.” However, neither the upper class Bengali speaking Muslim leaders and nor the Bengali Hindu leaders did hesitate to woo the support or sympathy from the Bengali Muslim settlers when the then Assam government made the unilateral determination in 1935 “to close down the Bengali classes” in the schools and “to encourage the setting up of new aided schools exclusively for Bengali children.”

Maulana Bhashani started holding numerous community meetings throughout Assam for the purpose of forming a viable resistance movement against the vested interests. It is evident that his intent of holding public gatherings was not only to garner mass support and the public opinions in favour of the disinherited Bengali peasantry in Assam but his initial mobilising efforts in Assam were also designed to convince the vulnerable Bengali immigrant settlers, the victims of the Line system, the paramount importance of binding together in self-defense. For instance, Maulana Bhashani organised a huge ‘Krishak Shommelon’ (Peasants’ Conference) at ‘Char Bhashan’ in 1929. The chief resolutions of this Conference were as follows: abolition of Line system, moratorium on the Bangal Kheda (Eviction of Bangalees) initiatives, the redress of the atrocities of Raja Probhat Kumar Barua (the Zamindar of Gouripur) over the Bengali Muslim migrants, and the introduction of uniform of weighing system throughout Assam (In fact, Maulana Bhashani’s serious efforts later led to the adoption of uniform weight system in Assam).

Maulana Bhashani devoted most of his efforts from 1929 through 1935-’37 toward building up numerous organisations of Bengali immigrants throughout Brahmaputra valley. Specifically, he had formed many peasant organisations for the sole purpose of articulating their demands. He also organised the agricultural laborers and landless peasants of Assam through the formation of “Assam Chashi Majoor Samiti” in 1937. During this period, Maulana Bhashani also started holding inter-provincial peasant conferences both in Assam and Bengal districts. For instance, Maulana Bhashani had assembled the ‘Bangla-Assam Proja Sommelon’ (Bengal-Assam Tenants’ Conference) in 1932 at Sirajgunj of the then Pabna district. One of the professed objectives of holding the inter-provincial tenants’ and peasants’ conference was to sensitise the people of the neighbouring Bengal about the discriminatory policies and initiatives of the Assam Government against the Bengali immigrant settlers in Assam. According to Amalendu Guha, “From 1928 to 1936, while still maintaining his contacts with Bengal, Bhashani used to move up and down the Brahmaputra to visit the riverside immigrant Muslim villages in accessible areas of Assam and organised them on the basis of a peasant programme including the demand for land. The colonisation of Ghagmari and Bhashanir char was due to his own personal efforts. People, suffering under the oppression of zamindars in Bengal, were in any case flocking to Assam in large numbers in order to settle on its beckoning wasteland. By 1936, Bhashani emerged as the accredited leader of the Muslim immigrants of Goalpara. He stood (contested) as a candidate in the 1937 election and returned to the Assam Legislative Assembly, formed under the Act of 1935. He (Maulana Bhashani) remained an important figure in Assam politics during the next ten years” (Amalendu Guha, “East Bengal Immigrants and Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani in Assam Politics, 1928-’47,” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Volume XIII, No. 4, 1976, p. 427).

Doubtless, the emergence of Maulana Bhashani as the ardent defender of the Bengali immigrant peasantry in Assam was spectacular. As a saviour of his fellow Bengali immigrant settlers in Assam, he had organised a viable resistance movement against both the Line system and the brutish Bangal Kheda movement in 1930s and 1940s. His was the most trusted voice during the agonising years of tears and fears of the repressed Bengali immigrant peasantry in the Brahmaputra valley of Assam. He relentlessly fought against all odds for establishing their rights in the desolated regions of Assam. Maulana Bhashani dedicated himself for a period of at least two decades for ventilating their fair grievances and articulating their legitimate demands. His defiance of the infamous Line system and his fight against the vicious ‘Banglal Kheda’ policies and ploys of the then Assam Government made him a charismatic leader in Assam and a ‘folk hero’ in his own time. Since Maulana Bhashani was one of the tormented Bengali immigrant settlers in Assam, his resistance movement can be characterised as the bold and creative defiance and mass rejection of various anti-immigration policies and ploys of the then Assam Government.

***

The cherished yearning of Maulana Bhashani’s early life and political struggle in the then greater Mymensingh district and in various districts of northern Bengal was to free the marginal cultivators, sharecroppers, and agricultural laborers from the yoke of the local landlords and their intermediaries and the money lenders. His struggle in the early phase of his political life both in northern districts of Bengal and the lower Assam districts can be characterised as a grassroots struggle for social justice. The emergence of Maulana Bhashani as the most charismatic peasant leader in Assam at a critical juncture was nothing short of a miracle for the discriminated and repressed Bengali peasantry in Assam. His grassroots level efforts towards building organisational infrastructures in rural regions of Bengal and Assam brought the most neglected and vulnerable segments of the society from periphery to the centre of the political spectrum.

There were a variety of voices against the infamous Line system and the brutish Bangal Kheda movement (also known as Bangal Kheda movement). There had been no dearth of criticisms of various anti-Bengali policies and ploys of the then Assam Government. Yet it was Maulana Bhashani who had emerged as the most selfless and dauntless champion of the most repressed and underprivileged Bengali peasantry in Assam. Indeed, his political struggle in Assam was deliberately designed and launched to dismantle the infamous Line system and to establish a moratorium on the Bangal Kheda movement. His heroic defiance of the Line system and his protracted fight against the Bangal Kheda ploys of then Assam Government represented one of the most courageous and principled stands for establishing the legitimate rights of the Bengali speaking immigrants in Assam. Maulana Bhashani’s homegrown, community based resistance movement against the Line system and the Bangal Kheda movement was deliberately designed by him to be a movement of the Bengali peasantry, for the Bengali peasantry, and by the Bengali peasantry in Assam.

Doubtless, Maulana Bhashani was a catalyst of the most authentic movement for accruing or establishing both civil and political rights of the Bengali immigrants in colonial Assam. His relentless fight for the salvation of the toiling masses and his uncompromising resolve to fight against all forms of discrimination, oppression, exploitation and injustices had actually rendered credible voices to the most repressed Bengali immigrants in Assam. Maulana Bhashani had imparted a heritage of simple lifestyle, selfless and untainted leadership, and uncompromising resolve to fight for social justice. As the founder of a sustainable resistance movement against the Line system and the Bangal Kheda movement, Maulana Bhashani provided a path-breaking service for the vulnerable Bengali immigrant settlers throughout Brahmaputra valley of Assam. His organised resistance movement against the brutish Line system not only had to overcome the hopelessness of the Bengali immigrant settlers in lower Assam districts but also had to confront the internalised psychological damage that the Government-sponsored Bangal Kheda drive had inflicted on those tormented souls.

Dr. M. Waheeduzzaman (Manik) is a Professor and the Chair of the Department of Public Management and Criminal Justice at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee, USA and can be reached at zamanw@apsu.edu or manikzz@hotmail.com.

(Reprinted from the FORUM of THE DAILY STAR, January 2012)

© thedailystar.net, 2012. All Rights Reserved

(REPRINTED FROM THE DAILY STAR, February 21, 2007 AMOR EKHUSHEY SUPPLEMENT)

DHIRENDRANATH DATTA: GLIMPSES OF A LIFE

M. Waheeduzzaman Manik

Shaheed (MARTYR) Dhirendranath Datta (1886-1971) was the harbinger of the formative phase of the Bengali language movement, and he had made history on February 25, 1948 by demanding that Bengali to be recognized as one of the State languages of the new nation of Pakistan even though his proposal was meant to be an amendment permitting the use of Bengali along with Urdu and English in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. During the early years of Pakistan, he had remained an ardent defender of the Bengali language both in the CAP and the East Bengal Legislative Assembly. He became a martyr of the liberation war of Bangladesh in April 1971. Despite his pivotal role in jumpstarting the formative phase of the Bengali language movement during the most defining moment of Bangladesh’s quest for freedom and self-determination, his name has thus far remained essentially forgotten and neglected. It is also ironic that there exists a serious paucity of literature on the formative phase of his life and political struggle.

Dhirendranath Datta was born on November 2, 1886 in a village named Ramrail, approximately three miles away from Brahmanbaria, a sub-divisional town of the then Tripura (then spelled as Tipperah) district (later renamed as Comilla district). Dhirendranath Datta was very intimate with his father, who was a very kind man, and he was very inspired by his father’s idealism. He inadvertently did not mention his mother’s name in his memoirs. However, he mentioned that his father got married with a daughter of Bhubanmohan Rakhhit of Chapitala village under Sadar subdivision of Tripura district. He lost his mother when he was only 9 years old.

After finishing his education at Ripon College, Dhirendranath Datta decided to go back to his home district to live and work, and he made this determination instead of seeking a job or pursuing a legal career in Calcutta, a city where he lived and studied for almost six years. He left Calcutta on February 27, 1910 to start a teaching job in a high school that was located in a remote village named Bangra under the jurisdiction of Muradnagar Thana of the then Tripura district. He worked there as Assistant Headmaster of Bangra Umalochan High (English) School from March 1, 1910 through February 2, 1911. Although he enjoyed his teaching job in that rural high school, he decided to quit this job to pursue a law practice at Comilla town. He formally started his law practice on February 8, 1911 in Comilla town, and he continued to be a distinguished lawyer there till his brutal murder in April 1971 at the hands of the murderous Pakistani army.

Dhirendranath Datta’s debut in Bengal politics dates back to his student days at Ripon College. His subsequent political life was enormously conditioned by the life experiences and insights that he had gained during his student days in Calcutta from 1904 to 1910. He was a first year F.A. student in 1905 when he got involved in the anti-British movement to annul the partition of Bengal. In those turbulent years, both the Indian National Congress and the Bengal provincial Congress were dominated by two groups of leaders. While Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920), Bipin Chandra Pal (1870-1932), and Aurobindo Ghosh (1872-1950) led the extremist group, Surendranath Banerjee was the leader of the moderates. Dhirendranath Datta was the supporter of the moderate group in the Congress. However, he was also deeply inspired by the dedication and oratory of Bipin Chandra Pal, the leader of the extremists.

Dhirendranath Datta worked as a volunteer at the annual meeting of the Indian National Congress which was held in Calcutta in December 1906, and he was deeply inspired by Dadabhai Naoroji’s demand for Swaraj (self-rule) for India. In 1908, he also attended the annual conference of the Bengal provincial Congress at Boharampur. Although he was deeply inspired by the Congress demand for boycotting foreign goods, he had protested when some delegates to the Congress conference at Boharampur proposed the creation of the so-called ‘Bentwood Chair’.

Dhirendranath Datta also participated in the social conference that was held in Comilla during the 1914 provincial Congress meeting, and he opposed a proposal for ‘widow marriage’. He regretfully recapitulated that incident in the following words: “I am saying this with a sense of shame that I had opposed the question of widow marriage even though I completely changed my view later about widow marriage.” In fact, he became a champion of various social reforms even within his own religion throughout his political career, especially during the years between the two World Wars. As a delegate from Tripura district, he attended the Bengal provincial Congress in April 1919 in Mymensingh, and on his return to Comilla he was devastated at hearing the news of the barbaric massacre of innocent civilians by the British on April 13, 1919 at Jalianwalabagh.

By mid-1920s, Dhirendranath Datta had emerged as a champion of various social reforms even within his own religion. In 1921, he was instrumental in founding the ‘Mukti Sangha’ at Comilla, the principal aim of which was to eradicate untouchability and caste system from the Hindu society. In 1923, he was also involved in the establishment of ‘Abhoy Ashram’ at Comilla. He also worked hard to forge a durable unity between Hindus and Muslims. Although he was a supporter of the Congress, he was greatly inspired by many admirable efforts of C.R. Das and his Swarajja party toward forging Hindu-Muslim unity. He was deeply shocked after he heard the news about the sad and sudden death of C.R. Das on June 16, 1925.

In its historic Lahore Session in late December 1929, the Indian National Congress had demanded ‘Purna Swaraj’ (full independence) for India, and it was stipulated that if the British Government failed to grant independence by January 26, 1930 then a Civil Disobedience movement would be launched throughout all provinces of India. Dhirendranath Datta made a conscious determination to follow through the Congress directives at any cost. When the time for real action against the British came on January 26, 1930, he wholeheartedly supported and followed all directives of the Congress through his direct participation in the civil disobedience movement.

Dhirendranath Datta organized a huge mass procession at Comilla town on July 2, 1930 protesting Motilal Nehru’s arrest. In defiance of the police order, the protestors under his leadership had refused to disperse the procession. On that day, he was mercilessly lathi-charged by the then British Superintendent of Police of Tripura district. Dhirendranath Datta and a host of other protestors were arrested on July 2, 1930 for defying police orders. After keeping him for several hours in the police station, the law enforcement authority presented him and his fellow protestors at the Deputy Magistrate’s Court in the afternoon of the same day. As a gesture of goodwill, the presiding Magistrate had expressed his desire to release them on bail on the condition that they have to attend the Court on the scheduled dates for trial. He firmly replied, “I refuse to recognize you as a Court.” The entire Court was filled with ‘Bande Mataram’ slogans. He was then sent to Comilla jail in the evening of July 2, 1930. After 15 days, he was summarily tried by a Court inside Comilla jail on July 17, 1930 in which he had again refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Court. This summary Court, presided over by the then Sub-Divisional Officer (S.D.O.) of Comilla, Nepalchandra Sen, who was his former roommate and classmate, sentenced him to three months’ rigorous imprisonment.

The dismal failure of the Second Round Table Conference in December 1931 and the arrest of Mahatma Gandhi immediately after his return to India on January 4, 1932 had given birth to the final phase of the Civil Disobedience movement. Dhirendranath Datta was arrested from his Comilla residence on January 9, 1932, and he was kept in jail for one month without any trial. This was his second internment. He was released from jail on February 8, 1932.

Aimed at courting arrest and violating the conditions of the notice, Dhirendranath Datta addressed a meeting in the evening at the Bar Library on the same day he was released from jail. He did not report to the police station. He was arrested at 8 p.m. on February 8, 1932. After he was kept in jail for a couple of days, he was put on trial in front of a magistrate inside the Comilla jail. He demonstrated his uncompromising commitment to the cause of the civil disobedience movement by refusing to take part in that trial but he had issued a pungent statement in which he stated the following: “The notice that has been served upon me is intended to kill the man in me and I have prevented this murder by disobeying the notice.” He was sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for one year. He was released from jail in February, 1933 after he had served the full term of his sentence. On his return to Comilla in February 1933, he found out that his family had to move out of his Comilla residence and started living in his village home under extreme financial difficulties. By 1933, the Civil Disobedience movement died out.

Dhirendranath Datta was overwhelmingly elected to the Bengal Legislative Assembly during the historic provincial legislative election in 1937. Although Dhirendranath Datta had to spend 18 months behind bars during his first tenure (1937-1945) as the member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly, he was one of the most articulate and committed legislators at a critical juncture of the history of the Indian subcontinent. Despite the fact that he was in the opposition in the provincial legislature, he was actively involved in the passage of the Bengal Tenancy Act, the Bengal Debtors’ Act, and the Bengal Money Lenders’ Act. In 1940, he was elected Deputy Leader (Kiran Shankar was elected as the Leader) of the Congress parliamentary party in the Bengal Legislative Assembly.

It was Dhirendranath Datta who brought a cut motion during the budget session in June 1945 that literally led to the downfall of Khwaja Nazimuddin’s provincial Government. Pursuant to the fall of the Khwaja Nazimuddin Ministry, the then Governor of Bengal had dissolved the provincial assembly in November 1945 and declared to hold the assembly elections during early (February-March) 1946. As a Congress candidate, Dhirendranath Datta was reelected in 1946 to the Bengal Legislative Assembly. On behalf of the Congress party, Kiranshankar Roy and Dhirendranath Datta were elected to be the Leader and Deputy Leader respectively of the opposition party in the assembly. Since the possibility of partition of India and the province of Bengal was gaining ground in 1946, he had to take some of the most critical decisions of his entire political career.

A life-long champion of Hindu-Muslim unity, Dhirendranath Datta was horrified to see the rise of communalism and the Hindu-Muslim riots in 1946. On the eve of the division of India, he had several options. As the Deputy Leader of the Congress parliamentary party in the Bengal Legislative Assembly, he could choose to opt for India where his political career would have been protected. He could realize that his future was at best problematic in a Muslim majority country if he opted for Pakistan. Yet Dhirendranath Datta made a conscious determination to opt for the new nation of Pakistan. On a matter of principle, he was unwilling to abandon his constituents. He became a member of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan (CAP) in December 1946 and continued to be a member of the CAP till this body was arbitrarily dissolved in October 1954. He attended the first session of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan (CAP) on August 12, 1947. He also attended the historic session of the CAP on August 14, 1947 in which Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, had transferred power to M.A. Jinnah, the newly appointed Governor General of the new nation of Pakistan.

Dhirendranath Datta had moved an amendment at the CAP on February 25, 1948 for adopting “Bengali” as one of the official languages of the CAP. It is clearly evident from his speech that he also demanded for adopting Bengali as one of the “State” languages of Pakistan. Among many others who were in the vanguard of the formative phase of the Bengali Language Movement, his role was seminal in the process of jumpstarting our resistance against those forces that were engaged in repudiating the rudiments of Bengali language and culture through the imposition of Urdu.

It is evident from whatever scanty literature is available on the formative phase of his life that his motto of social service was greatly shaped by his concern for his country and his compassion for common masses. Doubtless, he was a good lawyer-politician. However, the most distinctive quality of this extraordinary man of integrity and honesty was that numerous opportunities could not add luster to his reputation. He never shunned the code of ethics of his legal profession. Nor did he ever deviate from his cherished life-long motto of social service. He was regarded as a person of amiable disposition, and it is fair to suggest that he was a gentleman par excellence. His was a graceful and courteous presence both inside and outside of the courtrooms or legislative chambers. However, on a matter of principle, he was not willing to demonstrate any kind of timidity even before the most powerful.

Dhirendranath Datta performed a yeoman’s service during the non-cooperation movement. At a personal level, however, he went through a social and political transformation during this historic movement. His direct participation in this volatile movement also gave him a rare opportunity to practice politics at the grassroots level in the rural areas even though his extended family had to endure untold financial difficulties. His life was also impacted by the historic Civil Disobedience Movement that was launched by the Congress in early 1930s. During different phases of the civil disobedience movement, he suffered three separate prison terms totaling a period of sixteen months.

As a participant in the Satyagraha and the ‘Quit India’ movements that took place in early 1940s, he was put behind bars twice for a total period of eighteen months. The way he had courted arrests and jail terms during those tumultuous years of Bengal politics is an exemplary testimonial to a true freedom fighter and patriot. Since his direct participation in various anti-British movements involved a great deal of personal risk and sacrifice, his deep sense of patriotism and selflessness and his commitment to other people can be identified as the chief incentive behind his bold decision of staying back in Pakistan for which he had to endure humiliation and various forms of hardship. However, his sacrifices did not go in vain. Dhirendranath Datta’s profile in courage that was demonstrated both before and after the partition of India and his role as a dauntless defender of the Bengali language and culture will be remembered beyond the boundaries of time.

Dr. M. Waheeduzzaman Manik is chairman of the Department of Public Management at Austin Peay State University and writes from Clarksville, Tennessee, USA. (His e-mail address is zamanw@apsu.edu or manikzz@hotmail.com).

(REPRINTED FROM THE DAILY STAR, February 21, 2007 AMOR EKHUSHEY SUPPLEMENT)

© thedailystar.net, 2007. All Rights Reserved

Dear Mr Manik

Thanks very much for this interesting piece.

with my best wishes

Amitav Ghosh

(REPRINTED BY THE AUTHOR FROM THE DAILY STAR, November 17, 2003)

The Daily Star Bhasani special

Maulana Bhasani — the builder of opposition politics

M. Waheeduzzaman Manik

Throughout almost six decades of his struggling political life, ‘Majloom Janoneta’ Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani was both a demanding spirit and a dauntless voice for freedom and emancipation of the humblest and the disinherited citizens against the overwhelming powers of the governmental machinery and the overweening grip of the ruling elite of the society. Doubtless, his unblemished long political career was characterized by a selfless dedication for championing the causes of the most underprivileged segments of our society. Indeed, he had an impeccable record of a life-long relentless struggle for the downtrodden and the disinherited. However, Maulana Bhasani was more than a spokesman of the peasantry and working class. His legendary name is also integral part and parcel of Bangladesh’s struggle for freedom and independence. He was both the maker and shaker of political events in the then East Pakistan during the most turbulent years of Bengla speaking people’s association with Pakistan. The seed of opposition politics and agitation was carefully planted by him in the then East Bengal in the formative years of Pakistan. He was also responsible for founding the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League (EPAML), the first viable opposition party in Pakistan. The main purpose of this commentary is to appraise the sanguine role of Maulana Bhasani as the builder of the politics of opposition and agitation in East Bengal in the formative years of Pakistan. Given the fact that he was intimately associated with all of the progressive movements during the Pakistan era, no attempt has been made to provide any chronological details of any of those movements within the limited scope and size of this paper. Rather, the intent here is to underscore Maulana Bhasani’s central role as the fearless organizer of a viable opposition in the then East Pakistan with specific reference to his pivotal role in the formation of the EPAML and some of his accomplishments as the fearless dissenting voice in the early years of Pakistan.

The genesis of the disintegration of Pakistan was conditioned, to a great extent, by Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s quest for installing the anti-Bengali collaborators and rightist Muslim Leaguers in both the party apparatus and the governmental structure of East Bengal. Indeed, the seed of colonial mode of governance in East Bengal was also planted by the Founding Father of Pakistan. A deliberate policy was quickly initiated for packing the East Bengal (East Pakistan) branch of Muslim League with their loyalists. Most of the celebrated Bengali Muslim League leaders were kept out of the newly revamped provincial branch of the Muslim League. Thus the chief intent of the Punjabi-Mohajir dominated Pakistani rulers was to perpetuate their colonial policy in the then eastern province of Pakistan through the use of the loyalist Muslim League government. Both Khwaja Nazimuddin and Nurul Amin regimes had willingly initiated and enthusiastically implemented various repressive and discriminatory measures in East Bengal for furthering and sustaining the colonial interests of the Karachi-anchored non-Bengali central government of Pakistan.

For instance, H.S. Suhrawardy and Abul Hashim, widely recognized as the stalwarts of Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BPML), were in the vanguard of Pakistan movement. Maulana Bhasani was the legendary figure in Assam politics, and as the President of Assam Provincial Muslim League, he had spearheaded the Pakistan movement in Assam. Yet, after independence, there was hardly any leadership roles for these dedicated and charismatic leaders in the newly installed government or in the provincial Muslim League. The followers of both H.S. Suhrawardy and Abul Hashim were specifically excluded even from the primary membership of the ruling party. Maulana Bhasani was also deliberately discredited and maligned by the ruling coterie immediately after his return to East Bengal from Assam. On his return to the then East Bengal in later part of 1947, he had won an assembly seat (through an uncontested bye-election) in East Bengal Provincial Legislative Assembly (EBLA) from South Tangail constituency. However, the provincial ruling coterie had hatched a conspiracy out to dislodge him from the Provincial Assembly. His election to the Assembly was declared null and void on flimsy grounds.?Above all, Maulana Bhasani was declared disqualified by the provincial governor to run for re-election or for holding any public office!

Maulana Bhasani had courageously confronted and challenged the Muslim League leadership in the then East Bengal through the formation of a viable political organization. Being essentially goaded and aided by the more liberal factions of the ruling Muslim League, various groups of dissidents, and other progressive forces of the province, he had formed the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League [EPAML] on June 23, 1949 (the word ‘Muslim’ was formally rescinded from the nomenclature of the party in 1955). There is no doubt that the establishment of this opposition party was a milestone at a critical juncture of the new nation of Pakistan. The EPAML, under the charismatic leadership of Maulana Bhasani emerged as the most effective opposition party in the early years of Pakistan. Maulana Bhasani was the President of the Awami League for eight long years (1949 through 1957), and during those turbulent years he sincerely tried to build-up this party as the most effective political instrument for ventilating and articulating the genuine grievances and demands of the people of the eastern province of Pakistan. Both Maulana Bhasani and the EPAML had played pivotal roles in articulating Pakistan’s Bengla speaking people’s cherished desire and quest for autonomy and self-determination. Maulana Bhasani and his party had undeniably played the most defining role in all of the progressive movements in the then East Bengal during the early years of Pakistan.

Notwithstanding the deliberate distortions of Bangladesh’s political history, it is a matter of fact that Maulana Bhasani was the most authentic founder of the Awami League. Many credible writers attest to the fact that he was the driving force behind the establishment of the EPAML in an era which was invariably dominated by the Muslim Leaguers. For instance, in his seminal assessment of the role of the Awami League in the political development of the then Pakistan, Dr. M. Rashiduzzaman underscored the central role of Maulana Bhasani in building-up a sustainable opposition in the then East Bengal during the early years of Pakistan: “If any one man should be given credit for the rise of an opposition in East Pakistan, it is Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani. Maulana Bhasani became a popular figure in the 1930’s when he organized the peasant movement in East Bengal and Assam. Later, in the 1940s he gave his support to the Pakistan movement led by the Muslim League. Maulana Bhasani was frustrated by the closed-door policy of the Muslim League in Pakistan, however, and eventually, it was under his leadership that the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League [EPAML] was born at Dacca, on June 23, 1949” (M. Rashiduzzaman, “The Role of Awami League in the Political Development of Pakistan,” Asian Survey, July, 1970).

Dr. Talukder Maniruzzaman has succinctly observed that the 1948-phase of the Bengali language movement had “spearheaded the formation of the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League (EPAML), representing both genuine social protest and the political ambitions of the frustrated Muslim Leaguers. Maulana Bhasani was elected President of the party and (H.S.) Suhrawardy soon after became convener of the All-Pakistan Committee of the new party” (Talukder Maniruzzaman, Bangldesh Revolution and Its Aftermath, UPL, 1988, pp. 20-21).

According to Dr. M.B. Nair, “Maulana Bhasani was primarily responsible for the growth of the Party [EPAML]. He united the various opposition groups and pitted them against the ruling Muslim League. Though Suhrawardy’s contribution to the formation of the [East Pakistan] Awami Muslim League was much less than that of Bhasani, his followers who were the best party workers of the undivided Bengal [Provincial] Muslim League [BPML], constituted the core of the party.” M.B. Nair also attests further about Maulana Bhasani’s dominant role in the formation of the Awami League: “The Awami League, the first Muslim opposition party in Pakistan, was founded by the dissident Muslim Leaguers. Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani was rightfully considered as the founder and guiding genius behind the organized opposition to the Muslim League government in East Pakistan” (M.B. Nair, Politics in Bangladesh: A Study of Awami League, 1949-’58, New Delhi: Northern Book Centre, 1990, p. 61 and pp. 248-249).

There were many instances where the Awami League-sponsored public meetings and processions were disturbed or dispersed by the “hired goondas” of the ruling Muslim League. As the principal founder as well as the first President of the EPAM, Maulana Bhasani and scores of his party loyalists and progressive forces had to face stiff resistance from the Muslim Leaguers, and they were also the victims of repressive measurers of both the central government of Pakistan and the reactionary provincial government of East Bengal. The hostile political environment of the then East Bengal is well reflected in the words of Dr. M. Rashiduzzamman: “The political climate for an opposition party was not favorable in Pakistan at that time. Only a few months after it [EPAML] came into being, an Awami League procession and meeting was lathi (baton) charged and teargased by the police. After this incident, nineteen Awami League leaders, including Maulana Bhasani, were arrested. In 1951, the Awami League public meeting scheduled to be addressed by Suhrawardy could not be held as the government imposed Section 144? in certain parts of the city. This repressive policy towards the opposition was the natural consequence of an attitude typified by a statement of Liaquat Ali Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan, at Mymensingh, East Pakistan, in December 1950: ‘Pakistan has been achieved by the Muslim league. As long as I am alive no other political party will be allowed to work here.’ “[M. Rashiduzzaman, “The Role of Awami League in the Political Development of Pakistan,” Asian Survey, July, 1970.].

Immediately after the formation of the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League, Maulana Bhasani started organizing and addressing hundreds of mass meetings throughout the province in order to arouse an awareness among the public about the ineptness of the repressive Muslim League government. He had also addressed many meetings in the city of Dhaka. For example, on June 24, 1949, in the first public meeting of the EPAML, held at Dhaka’s Armanitola Maidan, Maulana Bhasani vehemently criticized the provincial government for its blatant failures in translating the pre-partition campaign promises into realistic and pragmatic public policies and programmes. He also stressed that the ruling party has miserably failed to fulfill the minimum demands of the people. In another public meeting, organized by the East Pakistan Muslim Student League (EPMSL) on September 11, 1949, he had earnestly appealed to the people to dislodge the repressive provincial government and the anti-Bengali central government of Pakistan. He urged the people to build-up resistance movement against the ruling coterie of Pakistan. In a mammoth public meeting on October 11, 1949 at Armanitola Maidan, Maulana Bhasani had forcefully demanded the immediate resignation of the then provincial government for exhibiting its ineptness in dealing with the food crisis. In defiance of the Section 144, Maulana Bhasani also led the ‘hunger march’ to press for redressing the food crisis in the province. Of course, the police force had lathi-charged the procession in which several dozen hunger marchers were injured. Maulana Bhasani was arrested under the Special Powers Act on October 13, 1949. However, his illegal detention was protested by spontaneous demonstrations throughout the province. He was kept in jail till he was released on December 10, 1950. In fact, the East Bengal government was compelled to release him from detention after he started a prolonged fasting inside the jail.

The Awami League leaders had vehemently opposed the anti-Bengali recommendations of the infamous Basic Principles Committee (BPC) Report. Although the anti-BPC movement was short-lived, it provided a golden opportunity for the Awami League to arouse an awareness among the masses throughout the province about the anti-Bengali constitutional design of the non-Bengali-Mohajir dominated central government of Pakistan. The anti-BPC movement took place in two phases, first one started immediately after the “Report of the BPC of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan (CAP) with regard to the future Constitution of Pakistan” was published in the national dailies on September 29, 1950.” There was a chorus of condemnation of the BPC report throughout East Bengal, and Awami League leaders spearheaded this movement. Awami League leaders and other opponents of this Report had clearly demanded that any future Constitution of Pakistan must ensure “full regional autonomy for East Bengal” and “recognition of Bengali as one of the State languages of Pakistan.”

Although Maulana Bhasani was in jail when the anti-BPC movement started, he joined the movement immediately after his release. While addressing a public meeting at Armanitola Maidan on December 24, 1950, he demanded immediate withdrawal of all anti-Bengali policies of both the central and provincial governments. On his sarcastic queries, the attendees in the meeting had expressed votes of no confidence in the central government of Pakistan and the East Bengal government. Neither Liaquat Ali Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan, nor Nurul Amin, the chief minister of East Bengal, had reason to feel amused or elated with such popular votes of no confidence in their governments on a day when the new nation of Pakistan was celebrating the Seventy Sixth Birth Anniversary of its founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah! Characterizing the BPC Report as both “un-Islamic” and “un-democratic,” Maulana Bhasani, in a pamphlet on January 1, 1951, directed his party workers to mobilize public opinion against the evil design of the ruling coterie of Pakistan. The stiff resistance from all quarters of people of the province had compelled Liaquat Ali Khan to announce “the postponement of any discussion” on the BPC Report.

The second phase of the anti-BPC movement started soon after the Second draft of the BPC report was tabled in the central legislature on December 22, 1952 by Khwaja Nazimuddin, the then prime minister of Pakistan. There was hardly any substantive modification of the BPC report excepting Nazimuddin’s new ploy of introducing the so-called parity-principle between the two wings of Pakistan. Maulana Bhasani and other leaders of his party were also in the vanguard of this phase of the anti-BPC movement. The patriotic people of the then East Bengal quickly rejected Khwaja Nazimuddin’s perverted version of the BPC Report. In observance of the Anti-BPC Protest Day, the All-party anti-BPC movement organized a large public meeting at Paltan Maidan on December 11, 1953. Maulana Bhasani had the honor of presiding over that historic meeting.

For his direct involvement in the 1952-phase of the Language Movement, Maulana Bhasani was arrested on April 10, 1952, and he put behind bar without trial till April 21, 1953. However, he did not deviate from his commitment toward making Bengla one of the state languages of Pakistan when the first council meeting of EPAML was held on November 14-15, 1953. The newly adopted party manifesto, adopted by the EPAML council meeting, demanded that “Bengla” should be recognized as one of the state languages of Pakistan. Nor did he compromise on the state language issue when the Jukta Front (United Front) was formed on December 4, 1953.

The United Front was formed in December 1953 as an electoral alliance of several political parties that included East Pakistan Awami Muslim League (EPAML), Krishak-Sramik Party, Nezam-e Islam Party, Gonotontree Dal, and Khilafat-e Rabbani Party. Maulana Bhasani, of course in collaboration with Sher-e-Bangla A.K. Fazlul Haque and H.S. Suhrawardy, was instrumental in the formation of the United Front (UF). Given the fact that the EPAML was the largest political party of this historic electoral alliance, the 21-point election manifesto of the Front reflected most of the popular demands that were thus far articulated by Maulana Bhasani and other progressive forces of the then East Pakistan. A great deal of credit was also due to his charisma, his relentlessness, and his oratory and organizational skills for the landslide victory of Front in 1954 election in which the ruling Muslim League was virtually routed out from the political scene of the then East Bengal. He had also vehemently criticized the central government of Pakistan for illegally dismantling Sher-e-Bangla’s United Front government in East Bengal. He was dismayed when both Sher-e-Bangla and H.S. Suhrawardy joined the central government of Pakistan as ministers in Mohammad Ali Bogora’s Cabinet without showing any regard for the pre-election pledges of the United Front.

Although the Awami League, as a political party, had vacillated or moderated its stand on the issue of “provincial autonomy” when Suhrawardy became the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Maulana Bhasani had never shelved or compromised his commitment to “full-fledged regional autonomy for East Bengal.” On a matter of principle, he had sharply disagreed with Suhrawardy’s version or interpretation of East Pakistan’s demand for full autonomy. He also openly criticized Suhrawardy’s advocacy for adopting the so-called “One Unit” plan for uniting or centralizing the western regions of Pakistan. Maulana Bhasani vehemently opposed Suhrwardy’s support for “Parity Principle,” an “anti-Bengalee” policy deliberately crafted into the 1956 Constitution in order to deny the numerical majority of Bangalees in the central legislature and the central services of Pakistan. Being totally disgusted with the deplorable state of political affairs in mid-1950s, it was Maulana Bhasani who had started demanding complete separation of East Pakistan from the rest of Pakistan, and his oft-quoted “Assalamalaikum” to West Pakistan was early warning for subsequent separation of East Pakistan from the rest of Pakistan.

Born in 1886 in the village of Dhangora of Sirajganj subdivision of the then Pabna District, Maulana Bhasani breathed his last at Dhaka Medical College Hospital at 8:20 p.m. on November 17, 1976, and he was buried at Santoosh, Tangail on November 18, 1976 with state honour. His stature as one of the greatest heroes of Bangladesh’s history comes not from a single action or accomplishment but from his lifelong commitment toward establishing or accruing social justice through political activism. He espoused a genuine cause for protecting, articulating, and enhancing the interests of the people of the then eastern province of Pakistan. Underneath the flowing beard, Maulana Bhasani was a serious man with a deep sense of compassion for the disadvantaged segments of the society. It is understood from whatever limited literature is available on the early phase of his life that he had learnt to be compassionate in his youth by doing compassionate acts for the underdogs of the society, and he cared for them even more as he grew older. He had remained a dedicated fighter till he breathed his last for accruing social justice for those people who were unjustly dispossessed, disinherited, abandoned, and humiliated. Maulana Bhasani’s action orientation and his lifelong commitment to social justice was the determining factor for his spectacular emergence as the most authentic planter and organizer of politics of opposition and agitation in the then East Bengal in the formative years of Pakistan.

Dr. M. Waheeduzzaman Manik is a Professor and the Chairman of the Department of Public Management at Austin Peay State University, Tennessee, USA.

(REPRINTED BY THE AUTHOR FROM THE DAILY STAR, November 17, 2003)

Dear Ms. Layli

Nice to meet with you. I saw that you are working with a great subject which is “Mobilising Muslim Subalterns: Bhashani and the political mobilisation of peasantry and lower urban classes, c.1947-71. I personally appreciate you. If you think that you will work more closely with the great leader Mawlana Bhashani Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani history, then you can tell me, may be me & my family will help you. I am the great grandson of Mawlana Bhashani. My contact details are;

E-mail: mehdi.tanim@gmail.com

Skype: mehdi.hasan.tanim

Cell: +8801711-931638

Great to know people around the world, especially the younger generation are working on this great leader. It gives us hope that struggle for the emancipation of the oppressed will succeed. This is all the more important when globalization and the worst form of capitalism are trembling on human rights, in particular labour rights. You may find my edited book, “Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Massess” a useful reference source. My 2nd edited book, “Moulana Bhashani: His Creed and Politics” will be out soon from Dhaka. You will also find Abid Bahar’s book based on his PhD thesis, “Searching for Bhashani: Citizen of the World” very useful.

Amitav Ghosh,

Please permit me to reproduce Mowland Bhasani’s picture in my book project on the Ganges basin. If you do not have the copyright, please guide me to the person that holds the right. The copyright holder will be credited in my book.

Your quick response will help me to complete the project in time.

Thanks in advance.

Best regards,

Dr. Miah Adel

Physics Professor

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff

USA

The picture was taken from the cover of the book.

best wishes

SEARCHING FOR BHASANI AND THE HUT

I was not involved in Bhasani’s politics. But my involvement with the topic Bhasani began when I was searching for a topic in leadership studies. This was meant to be a Sociological research.1 I was resolutely thinking about Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s life as a theme for my research. Professor Sheila McDonough, (a Canadian scholar on South Asia) redirected my interest to do research into the life of Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bashani, (she thought due to Bhasani’s ascetic religious life and his selfless political leadership, he was as if the Mahatma Gandhi of Bangladesh, she also added that Bhasani had a long life and studying the life of Bhasani would be similar to studying the history of the birth of Bangladesh). She also noted it will also give me the opportunity to understand Bangabandu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the other Bengali leaders. True, Bangladesh is the country of my birth but I had permanently left and from a distance I remained in touch with the people through my academic pursuits and when I sought to know more about it, I recognized the life of Bhasani as a topic would match my own interests.

Soon I recognized that Bashani was a political leader who with the other leaders of his time shaped the politics of the subcontinent in general and Bengal and Bangladesh in particular. Bashani was born in British Bengal in the later part of the 19th century in the remote Pabna district of present day Bangladesh. He was a Sufi religious mystic and a peasant leader. While most leaders with the change in fortune turned from rural living into the status of Calcutta babus, all his life Bhasani lived like a Brngali rural peasant. He fought against the British, against Pakistani military leadership and in the independent Bangladesh he always supported Bangabandu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who had been his political associate but not surprisingly disapproved Bangabandu’s one party BKSAL politics.

Among many of his accomplishments, Bhasani played a very important role during the 70’s in the liberation war of Bangladesh in which I was also directly involved. Ironically, I never knowingly attended his political meetings personally, although I was aware of his activities through the media. I remember in 1967, once I was on my way to Kanungopara College in Chittagong to meet a family member, I saw Bashani at a close range. I saw him speaking at a meeting of rural peasants from a podium by the side of a rural road. I still remember that I was a curious passerby drawn to the thunderous noise coming from the roadside gathering where I saw him, then already an old man, speaking to the rural peasants. From his outfit and appearance he looked like a rural Bengali peasant, talking with a very angry face, his teeth partially out. I remember that before this encounter, I didn’t know who he was. I inquired about the name of this person. I didn’t then even in my dreams know that the life of this person was going to be my topic of great interest. I would have forgotten both his name and this incident had I not remembered the very angry look in his face and his teeth, that seemed almost about to bite something or somebody. That was my first impression of a political leader who could be very angry about something I did not know and I didn’t want to enquire about at that time. Without understanding the depth of the matter, I remember, I left the place to my journey’s end.