January 19, 2000

On board the Megha

Sundarbans

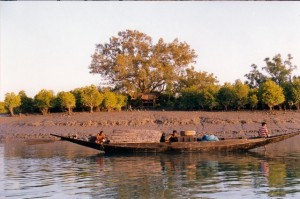

Stopped for the night at ‘Gerafitola’, after leaving Netidhopani and passing through Chamta Island. On the way, Haldipari – going down the Mayadwip river – then just after sunset we came across a fishing boat and stopped. A group of about eight fishermen – our ‘guide’ hectored them into giving us some fish; we insisted on paying, despite his protests.

The fishermen went back to drag their nets along the shore again, and we arranged to moor the bhotbhoti (motor-boat) alongside theirs for the night. We pulled into a small khal and anchored midstream. After a while they pulled up beside us. Bright moonlight. The mangrove covered shore eerily close.

It’s the kind of place that the Forest Dept’s guards are terrified of but our boatmen seem quite unconcerned and very happy to anchor here. We could have anchored on the river, which is very wide, but they were worried about sudden gales.

A fishing boat came up and moored itself to our bhotbhoti. We saw in the distance, the lights of another boat approaching up the khal; it turned out to be our friend from Satjelia – Mohanlal the Baule [or ‘bauliya’ – spell-maker] and his son Subhash.

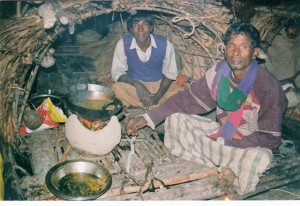

We are now sitting in his boat as I write; he is cutting fish, has caught only two today.

Mohanlal knows many mantras that are effective with animals but he says that no mantras are ever said during fishing because that would freeze the fish and close their mouths. His boat is a nauka, covered with a chhoi –

reeds hooped over curved bamboo. The floor, or deck, is made from switches of goran-kath and planks of phulkath [two kinds of mangrove wood].

Earlier in the day we saw the family

collecting firewood near the village.

They’ve brought along a stock so they won’t have to go ashore to collect any more.

It’s taken them one and a half-hours to come here from Satjelia, with their one sail hoisted.

They had the wind behind them – Mohanlal explains that they cannot go against the wind with this sail. It is square, primitive – he calls its charkona paal or chouko paal [square sail].

But he does know of a sail which can be used against the wind – he calls it kaanir badam; it is evidently a kind of lateen sail, tall and triangular. It is widely available, he says, and not necessarily expensive, but it is not possible to attach it to a boat like his. It draws very hard and might upset a small boat like this one. As he says this, he is kindling his unon [stove].

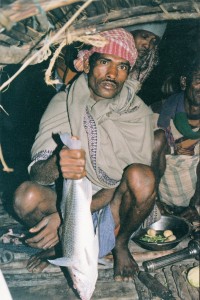

Now a third boat fishing boat is approaching. Mohanlal’s jamai [son-in-law] and his shejochhele [2nd oldest son] are in it. They have caught a big fish with a line: they call it jaba – it is a very beautiful fish. It would sell in Basanti for Rs 40/- a kg and in Kolkata for Rs 60/-. But most of the money would go to middlemen.

This is a strangely serendipitous meeting, deep in the forest, absolute stillness everywhere, the curtain of mangrove just a few feet away.

Both boats will light their fires; they will cook separately but will eat together. Mohanlal says that other fishermen always gather around his boat because they know that he will be able to protect the khal [creek] against danger – this is called para bondhi [closing the neighbourhood]. It is like a little floating village around our boat now, with all the little boats moored together in the middle of the khal.

Mohanlal’s father and grandfather also ‘went into the jungle’ (jongol korto), and his grandfather was also a bauliya [spell-maker].

Mohanlal explains that bauliyas know many different kinds of mantras: the khilen mantra shuts the tiger’s mouth; the alesh mantra makes the tiger drowsy; the chalan mantra drives the tiger away (he always says this in places where he spends the night). The jalan mantra gives the tiger a burning sensation and compels it to run away.

Before Mohanlal says the mantras he has to say the names of five fakirs (Ali Madhob Fakir; Moghlesh Fokir; Jalal Fakir; Mongolesh Fakir and Moniruddin Fakir) and five bibis (Bon Bibi, Phul Bibi, Gulal Bibi, Dulal Bibi and Fatima Bibi).

Mohanlal says that Bauliyas like himself often fall prey to tigers. This is because the Bauliya is intimate with tigers, and also interferes with them – shutting their mouths, keeping them away – so he courts danger. It is the same as when you exorcise a ghost in someone’s house, he says – that ghost is likely to follow you to your own house. Whether it is a bhoot [ghost] or bagh [tiger] it will look for an opportunity to haunt you. That’s why you have to be very careful with your mantras. You should not say them on Purnima [full moon] or Amabosya [moonless] nights; or on Fridays – because it is the Jumma for Muslims. Similarly a Bauliya cannot eat crabs, tortoises, and pork – for these things are all haraam for Muslims. If he eats crabs his ears will pop and make noises. Because of all this, he says, tigers are both attracted to and repelled by Bauliyas.

[for the story, see chapter titled ‘The Glory of Bon Bibi’ in The Hungry Tide]

Mohanlal calls his spells maal [goods/cargo]. Before you do the maal you have to pick up a little bit of earth and put it on a lead. There are many other rules to be followed. A bidi can’t be thrown away, either on land or the water – it must be put back on the boat. Blackened pots cannot be put into the water, or charred wood. It is only when these rules are broken, says Mohanlal, that the tiger gets its chance.

Hi,

I love reading about the Sundarbans, it sounds so magickal and so alive. The Hungry Tide is one of my favourite novels – I recently used it in my dissertation (I was looking at the importance of Nature and humanity’s relationship with it).

Your books are wonderful. I love In An Antique Land also. And The Glass Palace. And just yesterday I finished The Sea of Poppies – can’t wait for the next part of the trilogy!

Anyhow i just wanted to say thank you so much for your books. As a British born Bangladeshi, your books somehow allow me to re-connect with my ‘homeland’, your portrayals are so alive and accurate that i almost feel as though i am there again.

Thanks again,

sabiya

Hi Amitav,

I have just concluded my experience of reading ‘The Hungry Tide’. It drew me within the world that you intricately weave around Sundarbans.

I was constantly trying to imagine a ‘structure’ in your writing, trying to draw parallels…Nirmal-Fokir, poetry-reason etc…The women characters in Kusum-Nilima-Piya-Moyna are strong personalities. But i felt that across time and space, your create e repetition of motifs/symbols. It seems as if you identify a particular ideal that a character like Nirmal exhibits, you make it reflect in Fokir. In the backdrop, you create the resonance between Nilima and Moyna (‘practicality’ in their perspective).

I was just imagining such ‘structures’. I have bought ‘Sea of Poppies’ and ‘River of Smoke’. I hope to let myself be drawn to the worlds and characters you create. In the hope that one day, i will sit down to write, for good.

Thank you

Sri