Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18

As a writer of fiction I am accustomed to creating characters and inventing stories. But I also often deal with historical sources, and every now and again I come upon something that serves to remind me that reality often exceeds fiction in its improbability. Certainly, I could never have invented a story like the one I am going to recount here. The events date back to the latter years of the First World War, when groups of Indian soldiers and paramedics were imprisoned in the vicinity of Ras al-‘Ain, in what is now Syria. Some of the worst massacres of the Armenian genocide occurred in the vicinity of this town, and through force of circumstances, the lives of the Indians and the Armenians often became closely intertwined.

The reason the story has survived is that one of the Indian prisoners happened to write about about his war experiences forty years later. His name was Sisir Sarbadhikari and his book Abhi Le Baghdad (or On To Baghdad) appeared in 1958[i]:

it was self-published and was probably only ever read by a handful of people. But the fact that the text was committed to print was crucial to its survival. It meant that a copy of the book had to be deposited in the National Library in Kolkata – this was the very copy that I sought out last year[ii].

Sisir Sarbadhikari was (as am I) a Bengali from Calcutta [now Kolkata] and he belonged to a middle-class Hindu family.

This adds greatly to the improbability of the story, for in the early years of the twentieth century the chances that a young man from such a background would find his way into the front lines of a military campaign were close to nil.

This is because Bengalis were not eligible for recruitment into the British Empire’s Indian army, which drew its soldiers (or sepoys) from certain specially designated ‘races’[iii]. Oddly, especially since Britain’s martial prowess was founded on her navy, the British do not seem to have regarded the term ‘martial’ to be relevant to sailors-

– for ‘lascars’ (Asian sailors) served on many naval vessels, and they were recruited mainly from coastal regions, such as Gujarat, the Konkan, Tamilnad, Orissa, and, very substantially, Bengal.

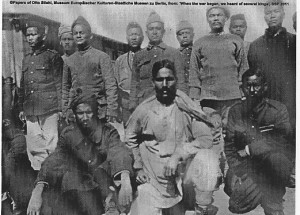

TheBritish Indian army’s recruitment policy excluded most Indians and was widely resented, partly because it was felt to be based upon demeaning racial stereotypes, and partly because it blocked access to one of the most important sources of employment in the colonial economy. The bar did not however apply to the army’s administrative and medical wings and many Bengalis found their way on to the military payroll through this route. When the First World War broke out some prominent Bengalis decided that the army’s medical services might be a means of furthering their claims to serve in the ranks of the regular military. To that end they offered to raise a unit of voluntary ambulance workers in support of the war effort. They reckoned that such an offer would not be refused at a time of crisis, and they were right. They were quickly granted permission to form a unit that came to be known as the Bengal Ambulance Corps (BAC). This was the unit that Sisir Sarbadhikari volunteered for in 1915.

[i] Indians at Home, Mesopotamia and France 1914-1918; towards an intimate history (in Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing (CUP, 2011) that prompted me to seek it out.

[ii] I owe many thanks to Dr. Swapan Chakravorty and Sri Ashim Mukhopadhyay of the Indian National Library, Kolkata, for their help in this regard. The page references (in parentheses) are to this copy of Abhi Le Baghdad.

[iii] Cf. Barua, Pradeep P., Inventing Race: The British and India’s Martial Races, Historian, 58(1), 1995, pp. 107-16; & Roy, Kaushik: Recruitment Doctrines of the Colonial Indian Army: 1859-1913, Indian Economic and Social History Review, 34 (3), pp. 322-54, 1997.