Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18 – 9

On Nov 19, Sisir left for Aleppo with some 50 seriously ill patients, on a mail train. They traveled in awful conditions: locked in a windowless compartment they had to relieve themselves in the corners.

But these circumstances did not prevent Sisir from noting that the stations were pretty, with tiled roofs – ‘like stations in Europe’ (p 143).

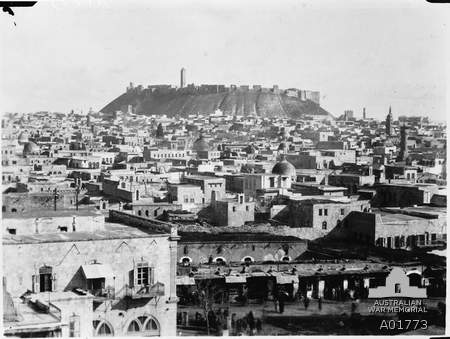

They arrived in Aleppo a day later. The city created a strong impression on Sisir: he writes: ‘Aleppo is not like the cities we have seen so far – Baghdad and Mosul. The houses are nice to look at; the roads aren’t bad. We hear that it looks like towns in Europea. The people on the streets look cultured; their clothes are nice; European costume predominates. There are people of many communities – Turks, Syrian Christians, Rums (that is Greeks) and Jews’ (p. 144).

On arrival Sisir and his patients were sent to the General Hospital (or Markaz Khastakhana) where some wards had been set aside for POWs (p. 144).

Sisir’s account of his stay at the hospital is surprising in many respects. Even though thousands of Armenians were dying in the camps of Ras al-‘Ain, a short distance away, in this Aleppo hospital Armenians were still an important presence. The commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Bagdasar Bey, was an Armenian and most of the doctors were Christians. Sisir writes that some were Nasranis (‘Nazarenes’) or Syrian Christians; others were Rumis (that is to say ‘Byzantines’ or Turkish Greeks).

Sisir was put into a ward that was run by an Armenian doctor called Saghir Effendi – ‘a wonderful man,’ writes Sisir, ‘he takes good care of the prisoners’. But Saghir Effendi was not to remain in the hospital for long. In January 1917, he stopped coming to the hospital. Sisir writes: ‘We hear that he has been sent on to the firing line. We were saddened to learn of this. We will never forget his kindness’ (p. 151).

Among the others who worked in ward, there was an Armenian woman called Marum who was especially kind – ‘How well she looked after us!’ Sisir remarks (p. 145). But this evidently did her no good in the eyes of the authorities for she was soon transferred to another ward and then dismissed altogether (p. 151-2).

It is impossible not to wonder about the state of mind of the hospital’s Armenian staff at a time when so many members of their own community were being killed in nearby camps. Although the situation of the Indians was completely different, the plight of the Armenians would certainly have resonated with them, since they too served an Empire in which they occupied a position of subservience.