Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18 – 7

Sisir Sarbadhikari recounts another story about the deserted Armenian village that he and his fellow POWs marched through on the northwards march from Mosul: when he went to look into a well a swarm of insects flew out. He explains that he had not intended to drink from the well; it was merely out of curiosity that he had looked inside. ‘It was not at all advisable,’ he writes, ‘to drink from these wells; there were Armenian corpses rotting in many of them.’ (129-30).

Over the next few days, as the prisoners marched northwards, they saw other empty, abandoned villages; a couple of them had been burnt down. After some forty days of marching they reached a town called Nisibeen[i], now on the border of Turkey and Syria.

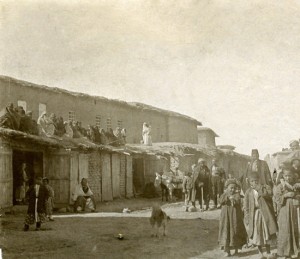

[This picture of Nusaybin is described as having been ‘taken by German military assigned to the British POW of Kut in Mesopotamia in 1916 during their march to Anatolia .

The shop keepers (Kurdish Jews) and their covered wives in white covers, migrated in mass to the Syrian town across the new border between Syria and Turkey post WW1 and formed the bulk of the Kurdish speaking Jewish community of Qamishli, considered the 3rd largest community of Syrian Jews after Aleppo and Damascus‘ (http://www.mideastimage.com/blog/?cat=30)]

Sisir writes ‘In antiquity Nisibeen was a Roman town. Examples of their building styles can still be found. On the river the Roman bridge is still standing and it is used by heavy army trucks… Nisibeen is quite a big settlement; food is easily available there. The Khabur River (the Habur of the Bible) flows through the centre of the town so water is plentiful. It’s different from the places we’ve seen so far; a fine place for bivouacking troops. The people are cultured and well dressed. None of the Armenian inhabitants are left. The local people who remain are all Muslims or Syrian Christians.’ (131-2)

Sisir would return to Nisibeen later, but his first stay there was quite brief. The prisoners soon continued their northward march, reaching Ras al-‘Ain on September 2. They had marched for 46 days from Samarra to Ras al-‘Ain, covering some 500 miles (133).

This is how Sisir describes the camp at Ras al-‘Ain: ‘For shelter [we had] Bedouin tents; like those at the Baghdad rest camp. There were gales all the time, with swirling sand – it was like sticking needles in the body.[ii] A hospital was nominally set up in a small room and serious patients were sent there. Medicines and supplies were few; but at least there was shelter from rain and wind… Rations were irregular … they’d come after two or three days. They didn’t give us any firewood for cooking; we’d have to wander three or four miles gathering twigs and camel dung. There were no trees to get branches from.’ (138)

[i] This town, now on the border of Syria and Turkey, is currently known as Nusaybin. But the 19th century traveler J.S. Buckingham refers to it as Nisibeen, and argues that it was the ancient ‘Nisibir’: ‘The first foundation of Nisibeen is of an antiquity beyond even the reach of records; since it is thought, by some learned divines, to be one of the places enumerated in the Scriptures, as built by Nimrod, “the mighty hunter before the Lord… Its name is more frequenlty written “Nesibis”, on the medals which are preserved of it. It is found to be written “Nisibis” in Greek authors, while the present pronunciation of the name, “Nisibeen”, or “Nesbin”, is said, by D’Anville, to be in conformity to Abulfeda, the Arabian geographer.’ ( Travels in Mesopotamia, London 1827, pp. 242-3).

[ii] E.A.Walker, as quoted by Heather Jones describes the Indians’ accommodation at Ras al-‘Ain in the following words: ‘they had ‘no shelter; only their own blankets, bare Turkish ration to live’’ (Imperial Captivities: Colonial Prisoners of War in Germany and the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1918, in Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, CUP, 2011) . Although there is no disagreement in the two accounts, I am struck by the marked contrast in tone; here, as in other parts of the narrative, Sisir’s description is remarkably matter-of-fact, his attitude stoical. Perhaps this was because his account was written long after the events, when the raw edges of the experience had been smoothed by the passage of time. Or was it because, as a private, and an Indian, he expected less and was more accustomed to difficult conditions?