Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18 – 13

Amongst Sisir’s particular friends in the hospital there was an Armenian called George. ‘His home was in Diyarbakir;’ Sisir writes, ‘his sons and daughters had all been killed; he had somehow managed to escape to Aleppo with his life. George was given the job of cleaning the toilets. There was a huge hall, with many toilets side by side. George lived in one corner of this hall – he ate and slept there. On cold evenings we used to sit with him and warm ourselves at his brazier, and then we would talk.’ (p.159)

Sisir’s stay at the hospital came to an end around June 1917, when most of the Indians were discharged. But for a while his luck held: amazing to relate, while other Indian POWs were dying of hunger and disease at Ras al-‘Ain, through a providential turn in the wheel of fortune Sisir and Bhola were sent to a rest-home (Liaqat-khana) to recuperate. The rest-home was in the Jewish area of Aleppo and they spent two months there. Only after their discharge did they learn that the Hindu POWs were to be sent to Ras al-‘Ain once again, while the Muslims would go to Islahiya, and the British to Belemedik. (p.165)

On returning to the vicinity of Ras al-‘Ain, Sisir found many changes. The railway line had been extended in the months that he had been away, and the Indian camps had advanced with it. The construction of the lines was being overseen by Germans, and they had taken charge of many of the area’s camps and hospitals.

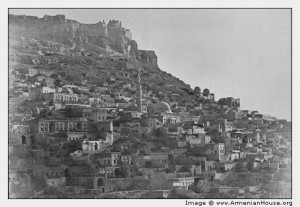

For a while Sisir was in a camp that looked towards the town of Mardin[i], which he describes as being ‘in the interior of Armenia’. He writes: ‘We heard that the city of Mardin was empty … there were no people in it. The houses were abandoned and it was like a ghost town.’ (p.168)

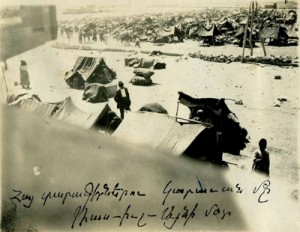

Sisir was then dispatched to another camp before finally ending up in a German-administered hospital in Nisibeen. It was here that he would become deeply enmeshed in the fate of Armenian refugees. ‘When I reached Nisibeen,’ he writes, ‘there were no Indian, British or Russian prisoners there. I was the only prisoner of war. The rest were Armenian mohajers (refugees); they were all women, only one had a little boy with her.’ (p.170)

‘I was given a small tent to live in and the big tents of the mohajer women were close by. There was no one to speak Hindi or English with, let alone Bengali – only with Meinhof [a German officer] would I exchange a few words in English.

When there were chats and conversations with the mohajers it was always in Turkish. One of the mohajers, old Mary, would patiently inquire after the smallest details of my home and family. She was sad to learn that I had lost my mother; she would say that this was why I had been able to go to war; if I’d had a mother she would not have let me go.’ (p.170-1)

Sisir was assigned to the camp’s hospital but his duties were mainly administrative. ‘Two Armenian mohajer boys, Yakob and Ilyas, worked for me in the office,’ he writes. ‘Yakob was some twenty years old; he was from a very ordinary family, and couldn’t do anything that required reading and writing. Ilyas was from a well-off background: he was about fifteen and knew a little French; he didn’t have much to do – his job was to write down telephone messages. (p.175).

‘Ilyas’s home was in Erzurum. He and his father, mother, older sister and brother lived there in peace until the war started. When the Turks began to kill the Armenians, Ilyas’s father and brother were not spared. They were dragged out of their Erzurum house and driven along, here today and there tomorrow. There were many others in their group – apart from all the Armenians of Erzurum, all the others in the towns and villages along the way were also herded together, with them. They were brought to a place where they were told: Now the menfolk have to be separated from the others – they have to go to a separate camp. (p.176)

‘[The Armenians] knew already that the men would be killed, so they realized that there was no other camp; it was a lie – they were actually being taken off to be slaughtered. There was much weeping and many tears, the women clung on to the men and would not let them go. But what could come of that?

The men were dragged off by force, Ilyas’s father and brother among them. The next day one male from that group managed to escape, bringing back the news that all the men had been killed. He had himself been badly wounded but was still alive. After a few hours he succumbed to his wounds.’ (p.176)

‘After that the women and children were driven along, to be abandoned in cities along the way. They had to forage for themselves, keeping themselves alive as best they could. On the way Ilyas was separated from his mother and sister; after much wandering he ended up in Nisibeen. When the Germans started building the railroad they assumed the responsibility for the Armenian mohajers and that made things a little better for them.’ (p.176)

‘From what we hear these terrible mass killings were not perpetrated by Turkish soldiers; they were done by Chechens and Kurds. Before we got to Ras al-‘Ain many Armenians had been brought there and killed. Sachin [a BAC volunteer] was in Ras al-‘Ain long before us; he told us that he had once witnessed the killings. A group of Armenians was made to stand up, their hands were tied, and their throats were slit one by one. Sachin said that those who did the killings were Kurds. There was a hill behind our camp in Ras al-‘Ain, it was on the other side that these deeds were done; Sachin once stole off there in secret and witnessed them with his own eyes.’ (pp. 176-7)

[i] Mardin once had a substantial Armenian population. The 19th century British traveler, J.S. Buckingham, in describing Mardin, writes ‘The population is thought to amount to twenty thousand, of which, two-thirds at least are Mohammedans, the remainder are composed of Christians and Jews. Of the Syrians, there are reckoned two thousand houses, of the Armenians five hundred, and of the Jews four hundred’, Travels in Mesopotamia, London 1827 (191-2).