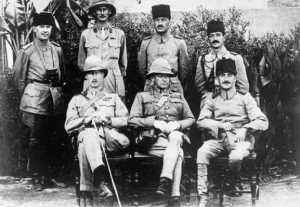

General Charles Townshend, the commander of the British-Indian force at Kut al-Amara, surrendered to the Ottoman commander, Khalil Pasha, on the 29th of April 1916. The force had been under siege since early December, 1915, and their stocks of food were completely exhausted.

This is Sisir Sarbadhikari’s description of what happened next.§

April 29

Turkish troops entered Kut after 1 p.m. When we first entered Kut as a victorious force in in September 1915 the Arabs had greeted us with ululations, dancing and applause; all that was acted out again now. Those who wanted to take it further kissed the uniforms of the Turkish officers; but many earned blows and kicks for their efforts. The Turkish officers said, ‘none of this is sincere, it’s just a staged act’, they understood that very well; if the British had come instead of the Turks it would have been the same… (94)

It was hard to know when the Turkish troops had been issued their uniforms. Their clothes were in a ragged state; many didn’t have boots. Roughly speaking their uniforms were like this – a coat of a khaki-ish colour, pants of the same colour, with puttees.

Most of them did not have shoes – those who had them were wearing either German shoes, or our old boots. They had knapsacks on their backs, with greatcoats rolled up on top. On their heads they wore a kind of topi, made of cloth. A small water-bottle; on their belts two big cartridge pouches on either side; in their hands a Mauser of the German pattern. Some had a big bundle tied to the top of their knapsack – five or six of them would eat from those. Their faces had been burnt to a coppery sheen by the sun; it was clear at a glance that they were a hardy lot.

No matter what their clothes, they were very good soldiers.

The officers’ uniforms were quite good.

A galabandh jacket, breeches and a tarbush on the head.

Boots with leather gaiters. (94-5)

Among the Turkish soldiers there were some who snatched our things.

One entered the hospital and pulled off Captain Kane’s boots; another grabbed Phani Datta’s watch from his arm.

But those who committed these outrages were few. Considering the poverty of the Turkish soldiers, what is surprising is that there wasn’t more looting. The looters were few. And when their officers were informed they gave the soldiers hell and made them return the goods…

We heard a Turkish soldier shouting ‘Postal, postal’ near our billet and ran to give him our letters – we had heard that they would make arrangements to send our letters to India so we had kept them ready. He explained to us that he wanted our boots and was willing to pay. We didn’t know then that ‘postal’ was the word for shoes. Anyway none of us sold our boots. Who would sell their boots then? For one thing there was no hope of getting more; and on top of that we heard that we would have to march six or seven hundred miles, and that too mainly through the desert, to get to our POW camps in Turkey.

May 1, 1916. From today our regiments began to leave Kut, one by one. For now to Camp Shamran, from there to Baghdad, where we would go from there nobody could say. Everybody would have to march. After five months of hunger, our physical state was such that it was difficult to march even a single mile – and now who knew how many miles we would have to walk?

May 2nd. The Turks took an interpreter from the Officer’s Hospital, right next to us. The man did not want to go but they forced him. All day there was the sound of firing in the serai – we heard that those inhabitants of Kut who were considered traitors – that is those who had collaborated with the English – were being shot. Did the interpreter go that way too?

…

Today down by the riverbank we saw an awful sight. In Calcutta we’d seen tripods made of bamboo in front of coal-shops, to serve as hoists. Seven such triangles had been erected – a man had been hung from each one; the bodies were still strung up. (95-7)

…

Among the seven were Kut’s shaikh, his nephew, his son-in-law, and a Jewish man, Sassoon. Their crime was to help the English.

They had tried to escape but had got caught. Later we heard that were whipped before they were hanged, so badly that the flesh of their backs was all torn up; Sassoon could not bear it and jumped off the roof of the sarai.

On the way back to the billet we saw a woman who was tearing out her hair and wandering about like a madwoman. Some said she was the shaikh’s wife, some said the daughter.

Their tragedy was a hundred times worse than ours. (98).

After this there were rumours once again that the Indian medical staff would be paroled and sent back to India.

8th. We ate what little we had and at about one p.m. we went to the riverbank. Our names were called out one by one and we were searched. What luck that they didn’t make me take off my boots! Otherwise I don’t know if this story would have been written. My diary was hidden in my boots.

…

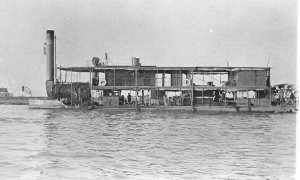

A Turkish officer got off the steamer ‘Julnar’. We thought that now they would let us get on the steamer. But that didn’t happen. The officer had brought orders countermanding the instructions for sending us to India; we would be imprisoned in Turkey. What our state of mind was then, it’s not in my power to describe. We all returned to our billet with our blankets and haversacks. (101)

On the 12th the prisoners embarked on steamers, to be taken to Baghdad.

The white or British soldiers are behaving very badly with the black or Indian sepoys; they’re even beating them! They say that it is because of the Indians that they lost at Kut! It’s unimaginably vile. The astonishing thing is that even when complaints are taken to the British officers, they do nothing.

The whites are sitting in comfort in the lower deck, every one of them has space to sleep. We’re on the upper deck – there’s no roof over our heads, and we scarcely have enough space to sit.

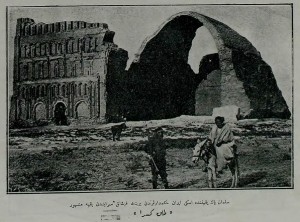

On the 13th the arch of Ctesiphon came into view.

Remembered the battle of Ctesiphon six months earlier. Remembered many things one by one – the night march, how Sailen used to walk as though he was fast asleep… things like that.

On the evening of the 17th Baghdad. The innumerable minarets of Baghdad came into view from a long way off. The steamer dropped anchor and we disembarked. (102-3)

Sisir Sarbadhikari spent the rest of the war in prison camps, in Turkey and the Levant. He survived the war and returned to India in January 1919.

Sarbadhikari’s account of his captivity is, in many ways, even more compelling than his account of the campaign. Some day, if time permits, perhaps I will write about it. But here my intention was only to provide a sense of the extraordinary vividness and drama of his narrative. These excerpts will, I hope, give readers some idea of why I believe this to be one of the finest of all First World War memoirs.

_____________________

§ In Abhi Le Baghdad [‘On To Baghdad’ by Sisir Sarbadhikari (Calcutta, 1958)]. The passages in colour are my own translations of excerpts from this text.

ß Capt. Charles Henry Weaver was with the Red Cross in Mesopotamia during the First World War. His remarkable photographs are posted at: http://www.mespot.net/

Dear Amitav

Thanks for posting the exert from the diary. It is really interesting

Thank you

Adrian