Sisir Sarbadhikari and his fellow volunteers of the Bengal Ambulance Corps arrived in Iraq on July 9, 1915. In the following months General Townshend’s British-Indian force pushed steadily northwards, towards Baghdad.

The Turkish army offered little resistance and such hitches as there were came mainly from within.

Yesterday (23rd October) a Pathan sepoy of the 20th Punjabis deserted after firing on a Sikh havildar. There were many Pathans in the 20th Punjabis: they had said quite clearly that they would not fire on Baghdad-sharif. So the 20th Punjabis have been sent back to Amara. (27)§

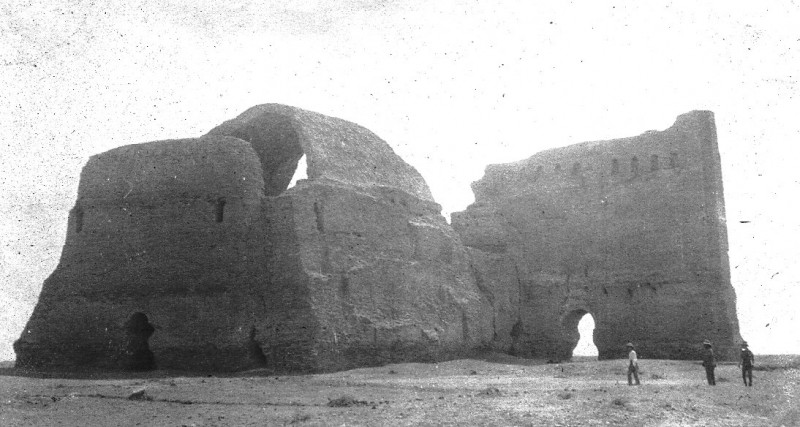

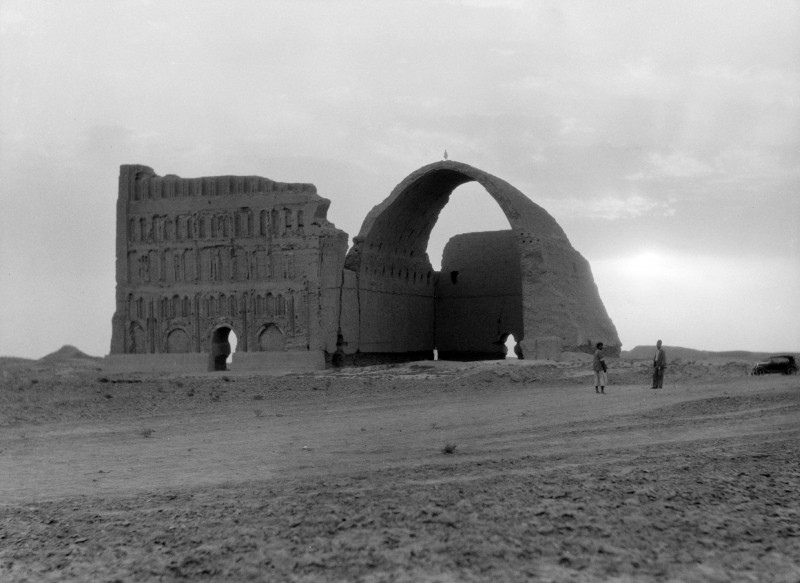

By late November General Townshend’s 6th Division was closing in on Baghdad. But between them and the city lay the ancient township of Ctesiphon (also known as Salman-i-pak), where a large Turkish force were waiting for them, in a well-entrenched position.

On the morning of November 21 the Ambulance Corps received orders telling them to be ready at all times because an attack could start at any moment. They were then told that the march would start at 9 that night.

‘Fall in’ was at seven and once again we went over the rules of night marching. But this time one thing that was emphasized was that we were to be very careful in using our water. In the event of victory in the battle (and we took it for granted that victory was inevitable) then we would have to march straight on to Baghdad and there would be no water for twenty or thirty miles.

Why did we think that victory was inevitable? Our 6th Division had repeatedly defeated the Turkish forces and taken places like Qurna and Nasiriya; we could not imagine that this division would now face defeat.

At 9 p.m. the 6th Division and the 30th Brigade began to advance for the attack on Ctesiphon. We moved noiselessly. Some twenty thousand men marching and not a sound. Even the horses that were pulling the cannon and mules of the transport carts were quiet. Even they seemed to understand that we were in enemy territory. The earth was soft and dry along the route so our boots, and the hooves of the animals, made no sound. It was almost unnatural – so many men and animals on the move but not the slightest sound. (33)

The march ended at 1 am on November 22nd . It was very cold that night: ‘We curled ourselves up like dogs and waited for the day to dawn so we could warm ourselves in the sun.’ (34)

When dawn came Sisir decided to make some tea and lit a fire. But one of the other volunteers warned him about wasting water – there might be none through the rest of the day.

I said: No water? Are you crazy? This ‘jackal fight’ will be over in a trice and we will be in Baghdad at around 3 in the afternoon; there’ll be no shortage of water then’. Perhaps when I said this the unseen goddess was laughing in secret: I certainly did reach Baghdad but not at 3 that day – after some six months and in completely different circumstances.

(The phrase ‘Jackal fight’ was thought up by Jacob [another volunteer]. And I can’t blame him. I’ve heard that in the British Parliament Lord Curzon had compared the war in Mesopotamia to a ‘river picnic’.)

By this time the fighting had started in earnest: the boom of cannons could be heard continuously. Battalions were advancing one after another, right before us. In front of us were the 66th Punjabis; now they moved too. We understood that it our turn was coming.

We began to advance slowly. Now there was no sound other than the boom of cannonfire and the report of rifles. We began to advance, with the whine of bullets passing over our heads and shells exploding behind us. We had to advance with great care. After every few moves we would have to fall into a ‘lie down’ position. In the meantime shells and bullets were falling like hail, all around us. Many were killed and wounded.

… The first wound that I bandaged was of a havildar in the 110 Maratha Light Infantry, by the name of Gul Mohammad. He had traveled with us on the P7 steamer from Basra.

As we advanced we gave the wounded ‘first aid’ and left them all together in dressing stations. There were many such small dressing stations…

No matter where we went, the arch of Ctesiphon was always visible….

Capt Murphy was commanding us now. He was a cool-headed man. At one point when the firing got very heavy, he ordered us to lie down. When we were prone we saw, about three hundred yards ahead of us, the men of the 104th battalion retiring at the double. We retreated a hundred yards and lay down again…

The hours slipped by but the ‘jackal fight’ showed no sign of coming to an end. All this while we were treating the wounded. Around us were innumerable dead bodies. Everyone started to say that a great number had been killed. Apart from our own brigade, wounded men from other brigades came to us too. Everyone was saying the same thing, that many had been killed and wounded. But we could see that for ourselves.

In the meantime my water bottle had run dry. My chest was splitting in thirst. Then I spotted a mule lying dead, with two containers of water (small tanks of galvanized tin) tied to it. I ran joyfully towards it, hoping to fill my water bottle. When I got there I saw that there wasn’t a drop of water in the tanks. The bullet that had killed the mule had also punctured the tanks.

There was a dead sepoy nearby, and his bottle had a little water. I used it to wet my lips and throat.

Soon it was dark. The fighting was still going on but not at the same rate as before… (35-37)

Later that night the troops began to pull back.

Those whose legs weren’t badly hurt went with us, leaning on our shoulders. We put two British officers whose legs had been badly fractured on stretchers; the slightest shaking would give them unbearable pain. One of them kept saying softly ‘Please don’t give me more pain than you can help.’ Around his neck was a gold chain with a cross; he was holding it in his fist. … (39)

We left behind those who were badly wounded. They couldn’t stand let alone walk. When they saw that we were leaving they began to weep, and who could blame them? They were very vulnerable in that condition. We tried to reassure them by saying that we would send transport for them soon. …

We didn’t have far to go but we had to move very slowly because of the wounded. We were almost walking on tiptoe because of the two British officers with fractures. On top of that there were many dead bodies on the road so we had to move carefully. We tried to not to step on them but it wasn’t always possible. There was no space for one’s feet. (40)

…

Ctesiphon, the next day and afterwards.

What I saw after I woke up on the morning of the 23rd is beyond my powers of description. On all sides, the corpses of men and animals. In some places they seemed to be in each others’ arms; in some places men had been pinned under animals and were lying there, groaning. In front of the trenches, along the lines of barbed wire, was where the greatest number of wounded lay. In some places men were hanging from the wires; some were dead (they were the lucky ones) and some were still alive. Here there was a severed hand hanging from the wire; there a foot. One man was hanging on the wires with all his entrails tumbling out. In some trenches four or five men had died with their limbs thrown over each other – Turkish, Hindustani, British, Gurkha, all mixed up together. (42)

One man’s limb in another man’s stomach, another’s in someone’s eye, that’s how they were lying – and in the midst of this some were still alive – bringing them out was impossibly difficult.

I saw a Sikh sitting with a smile on his face – his white teeth were shining in his black beard. I thought, why are you smiling at a time like this, have you lost your head? When I approached I saw that he had been dead a while. He must have grimaced in pain as he was dying. (43)

…

As the hours went by we became increasingly thirsty. During the night we’d suffered from the cold, now we were suffering from the thirst. The wounded called for water with increasing desperation. The white soldiers said: ‘A drop of water for Heaven’s sake.’ We had to turn our water bottles upside down to show them that we had no water.’ (44)

Then the fighting started again. It seemed as if the Turkish trenches that had been seized the day before, were now being fought over again. At around 3 p.m. bullets were raining down on the V.P. [the designated ‘Vital Point’]. That was exactly where the wounded had been brought. Many of them were killed by bullets and many sustained new wounds. Those who weren’t hit could see others being wounded around them and tried to get away – even though they were unable to move. They were seized by a kind of terror – and who can blame them?

The wounded were then loaded on carts and moved back. But the convoy did not have a large Red Cross flag, so it was mistaken for an ammunition column and was heavily shelled by the Turkish artillery.

Here too many of the wounded were killed and many acquired new wounds. Many mules were killed. Some were panicked by the bullets and ran into the fields, dragging the wounded with them. Then darkness fell and the bombardment ceased so we were ordered to bivouac there.

By that time we were desperate for food and water. Twelve hours before we had been given two chapatis and a bottle of water, after that nothing. Amulya [another BAC volunteer] and I set off to look for food and found a piece of bread in the haversack of a dead white soldier. We divided it between us and were eating it in the dark, when we realized that the bread had a peculiar taste. Then we understood. The bread had soaked up the soldier’s blood, hence the taste. (45)

§ The page references are to Abhi Le Baghdad [‘On To Baghdad’ by Sisir Sarbadhikari (Calcutta, 1958)]. The passages in colour are my own translations of excerpts from this text.