Sisir Sarbadhikari’s On to Baghdad has much in common with Kalyan-Pradeep. Sarbadhikari’s war experiences in Mesopotamia and his time in captivity overlapped closely with Capt Kalyan Mukherji’s. They were in the same places, often at the same time, and they knew each other. They were both from Calcutta and belonged to families of lawyers and doctors; they were both well-informed and widely-read.

Capt. Mukherji was in his early thirties at the start of the war; he was a married man, with a child. He was also a doctor, and a career officer of the Indian Medical Service (the medical wing of the British-Indian army). Sarbadhikari was in his early twenties, and he volunteered to serve as a private in a hastily-formed auxiliary medical unit – the Bengal Ambulance Corps. Sarbadhikari mentions Capt. Mukherji a few times, but his name never figures in Capt Mukherji’s letters to his family.

There is some degree of overlap even in the history of the two texts. Capt. Mukherji’s letters became the basis of his grandmother’s book, Kalyan-Pradeep, which was published eleven years after his death in a POW camp at Ras al-‘Ain. Sarbadhikari’s book was published forty years after the war, in 1958. Santanu Das, who has interviewed his daughter-in-law, Romola Sarbadhikari, tells me that she was instrumental in collating his notes and persuading him to write the book.

Both books were self-published: evidently, publishers did not think that these books would be of interest to the reading public of Bengal. It is easy to imagine how dispiriting this must have been to the two families. It is a tribute to their persistence that the texts found their way into print and have survived.

But these similarities are, in a sense, incidental: in form, style, and even, content, the two books bear almost no resemblance to each other.

This is how Sisir Sarbadhikari’s story starts.

1914. I’ve just passed my B.A. and have nothing much to do. No that isn’t quite correct, I’ve actually entered my name in the rolls of the Law College, and am looking for a job. In the meantime the First World War breaks out. Of course, at that time nobody kew that this war would come to be known as the Great War, or that some twenty years later it would earn the designation of ‘First’ following on another World War. When we first heard the news none of us were particularly interested. Who cared where Sarajevo was and which Archduke had been assassinated there? We barely took the trouble to look at the reports in the newspapers. We thought it was just a little bit of bother that would soon be sorted out.

But it wasn’t. On August 4, England declared war on Germany and Austria. Within a few days troops were dispatched from India to France. Now everybody was suddenly eager to know more about this war.

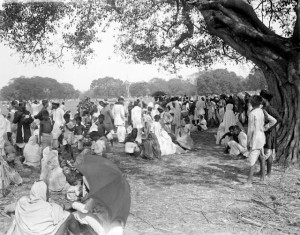

At this time Bengali leaders decided that this was a golden opportunity to establish a foothold in the armed services [i]. They held a meeting in Calcutta’s Town Hall and it was resolved that they would write to the Viceroy requesting permission to send an Ambulance Corps, staffed with doctors and volunteers, to the front. Soon it was learnt that permission had been granted and that recruiting offices had been set up. One such office was set up in College Square: I went there, entered my name and signed the forms.[ii]

Sarbadhikari was so keen to volunteer that he actually pulled strings to get into the Bengal Ambulance Corps. Fortunately for him an uncle of his, a prominent doctor, had played an important part in setting up the Corps. Evidently a bit of nepotism was necessary even for someone who was volunteering to risk his life on foreign soil.

Sarbadhikari’s eagerness to join was largely based, by his own account, on the ‘Spirit of Adventure’ (he uses the English phrase). This same spirit, he writes, would prompt him to volunteer for service again during the Second World War when he was over fifty. So it happened that he found himself under siege in not one but two world wars, in the second instance in Imphal in 1942, when the town was besieged by the Japanese.

[As I was writing this I discovered, to my astonishment, that I have a personal connection with Sisir Sarbadhikari, of the ‘six-degrees-of-separation’ kind. I happened to google ‘Bengal Ambulance Corps, and the first name to come up was that of Ranadaprasad Saha, a Bangladeshi philanthropist and industrialist. He and his family were friends of my parents and I remember visiting his house in Narayanganj many times as a child. I was very young then and had no idea that he had served in Mesopotamia. But I do remember how shocked we were to learn that he had been seized by the Pakistani Army during the 1971 war. He was never seen again.]

[i] Bengalis, like most Indians, were not classified as a ‘martial race’ hence were not eligible for recruitment into the armed services; they were thus shut out of one of the country’s most lucrative job markets.

[ii] ‘Author’s Introduction’.