In Redburn, his autobiographical novel about his first voyage, Herman Melville tells the story of how he met the lascars of a ship called the Irrawaddy, in Liverpool.

Stepping on board the ship he found a group of lascars eating on the fo’c’sle deck: “Among them were Malays, Mahrattas, Burmese, Siamese, and Cinghalese. They were seated around ‘kids’ full of rice, from which, according to their invariable custom, they helped themselves with one hand, the other being reserved for quite another purpose. They were chattering like magpies in Hindostanee, but I found that several of them could also speak very good English. They were a small-limbed wiry, tawny set; and I was informed, made excellent seamen.”[i]

The chain of command on the Irrawaddy was no different from that of any other ‘country boat’ that made the crossing to England: such vessels might be built in India, they might be owned by Indian merchants, they might be manned entirely by lascars, but their officers were almost always white ‘Free Mariners’.[ii] The Captain of the Irrawaddy accordingly, was an Englishman, as were also the three mates, master and bo’sun. “These officers lived astern in the cabin where every Sunday they read the Church of England’s prayers, while the heathen at the other end of the ship were left to their false gods and idols. And thus, with Christianity on the quarter-deck, and paganism on the fo’c’sle, the Irrawaddy ploughed the sea.”[iii]

One night, Melville got into a conversation with a lascar who gave his name as ‘Dallabdoolmans’. Melville found that he spoke good English, and was quite communicative ‘like most smokers’.

“It is a Godsend,” wrote Melville, “to fall in with a fellow like this. He knows things you never dreamed of; his experiences are like a man from the moon – wholly strange, a new revelation. If you want to learn romance… take a stroll along the docks of a great commercial port. Ten to one, you will encounter Crusoe himself among the crowds of mariners from all parts of the globe.”[iv]

Melville wrote Redburn from memory, when his first voyage was long in the past, but his visit to the Irrawaddy clearly made a powerful impression, for more than a decade later he was able to recall Hindusthani/Bengali words, such as sagoon, teak. He probably got the lascar’s name wrong, but the fact that he went to the trouble of recalling it is still of enormous significance – for in the annals of 19th century nautical writing the lascar, when he appears at all, is almost always a figure unnamed. Melville’s account is almost unique in this regard, and his memory was perhaps not entirely to blame for the mangling of Dallabdoolman’s name. It is easy to imagine that a nosy young writer who inquired after the name of an Asian or African transient in today’s Europe would be given a similarly misleading answer. Lascars like Dallabdoolmans were probably wary of making themselves conspicuous, and this may be one reason why the names recorded on 19th century ships’ manifests seem too sketchy to be real markers of personhood. For it is a fact that when a lascar stands out from the generality of his brethren in the historical record, it is almost always because he is the subject of some kind of legal or disciplinary action.

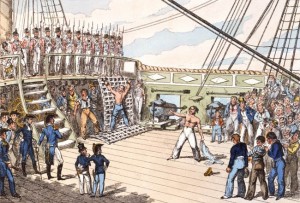

Thus for example, we have the case of Abdul Rhyme, in 1649, a lascar who who was convicted while at sea, for having sex with a fellow member of his crew, a sixteen-year-old Londoner, by the name of John Durrant. Several witnesses testified that the relationship was consensual, but in the eyes of the ship’s captain this served only to deepen the gravity of the offence since it implied that the English boy had willingly entered into a liaison with a ‘Hindoosthan peon’.

The accused were both sentenced to forty lashes and it was specified that their wounds were to be rubbed with salt.[v]

Or there is the 1814 case in which a lascar was whipped to an inch of his life in East London: the incident caught the attention of a magistrate and became something of a scandal. The lascar in question had been whipped by none other than his own serang who, on being arraigned, offered the defence that he was merely applying the custom of his trade, with the consent of his employers, the East India Company.[vi]

[i] Herman Melville: Redburn: His First Voyage, Being The Sailor Boy Confessions And Reminiscences Of The Son-Of-A-Gentleman In The Merchant Service, Anchor Books, New York, 1957, p. 164.

[ii] See Anne Bulley’s The Bombay Country Ships, 1790-1833, Richmond, 2000, p. 207 – 210.

[iii]Herman Melville: Redburn: His First Voyage, Being The Sailor Boy Confessions And Reminiscences Of The Son-Of-A-Gentleman In The Merchant Service, Anchor Books, New York, 1957, p. 165.

[iv] Ibid, p. 166.

[v] B.R Burg, Sodomy and the Pirate Tradition: English Sea Rovers in the Seventeenth-Century Caribbean, New York University Press, New York, 1995, p. 146-7.

[vi] See Isaac Land, Customs Of The Sea: Flogging, Empire, And The ‘True British Seaman’ 1770 To 1870, Interventions, 3:2, 169-185, 2001.