Further to my post on Zoroastrian Hong Kong, Shernaz Italia writes:

Dear Amitav,

There seems to be some degree of confusion regarding the disposal of the dead in the Zoroastrian tradition. A brief explanation:

Zoroastrian tradition considers a dead body a pollutant – and hence had rules for disposing of the dead as “safely” as possible so as not to pollute either earth or fire. This is why the bodies of the dead were placed on an elevated surface or tower – Tower of Silence or dahkma – exposed to the sun and birds of prey.

In the Iranian Zoroastrian tradition, the towers were built atop hills or low mountains in desert locations distant from population centers. In the early twentieth century, the Iranian Zoroastrians gradually discontinued their use and began to favour burial or cremation.

The decision to change the system was accelerated by three considerations: The first was the establishment of the Dar-ul-Funun medical school in Iran. Since Islam considers unnecessary dissection of corpses as a form of mutilation, thus forbidding it, there were none to be had officially, and the dakhmas were repeatedly broken into, much to the dismay and humiliation of the Zoroastrian community. Secondly, while the towers had originally been built away from population centers, the growth of the towns led to the towers now being within city limits. Finally, many of the Zoroastrians themselves found the system outdated and substituted the dakhma with a cemetery. In the early days graves were lined with slabs of stone, concrete or rocks, to prevent direct contact with the earth. In 1970s the dakhmas in Iran were shut down by law.

India is the only place where Towers of Silence remain in use, and there are very few in number. The concentration of Parsis in a geographical area dictated the type of disposal. Very early on a decision was taken that burial in cemeteries – Aramghas – was acceptable in places where there were not enough Parsis to maintain a Tower of Silence; for instance Ajmer is the furthest north in India where there is a tower. In hill stations in India, a section of the Christian or Catholic cemetery was set-aside for Parsis.

The same applied to Parsis who died overseas, hence this beautifully maintained cemetery at Hong Kong. A Trust was formed in 1822 in Macao for the establishment of a Parsee cemetery there. The first Parsi association, known as the ‘China Canton Anjuman’, was formed in Canton in 1834. In1845. A wider Anjuman body covering Hong Kong, Canton, and Macao was created for establishing and maintaining burial grounds and having places of association. In Hong Kong, the first premises for use of the Zoroastrian community were rented in 1852. In 1993, the 23-storey Zoroastrian Building that you have photographed so beautifully on this blog was inaugurated.

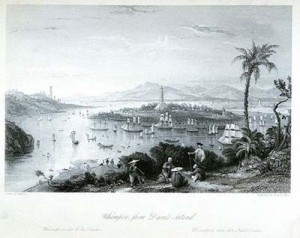

To this Shernaz appends an excerpt from an article in a magazine, Zoroastrians Abroad, on the Parsi cemetery in Whampoa (Huangpu).

“Fourteen Zoroastrian graves in the cemetery at Huangpu, also known as Whampoa, an industrial city in south-east China in the Pearl River Delta region, a part of Guangzhou province, have been restored by the Chinese government. A group of 30 Zarthoshtis from Hong Kong made a three-day visit (April 4 – 6, 2008) to the Chinese mainland to see the place for themselves. “We were under instructions not to burn incense and were content to pay homage to our dearly departed with a silent prayer,” writes Jal Shroff, president of the Zoroastrian Charity Funds of Hong Kong, Canton and Macao, recounting the 10-year development.

“The actual graveyard site is on the top of a hill within the grounds of the CSSC Guangzhou Huangpu Shipping Company Limited. A guarded gate blocked access to all vehicles and pedestrians initially, despite the necessary permits having been obtained. We were, however, eventually let through and made our way up the neatly paved 150+ steps…Some of the inscriptions were worn out and hard to read; others had only parts of the inscription because vandals had made away with pieces of masonry. One grave could not be restored because a tree had grown from underneath it and displaced it completely,” notes Shroff.

“While the age of the deceased is not mentioned on three graves and one is minus a headstone and hence there is no record of its contents, the men buried there seem to have succumbed at an early age, the youngest being 21, the eldest 55. There appears to be no notation to indicate the cause of death. And though there are no adult women buried there, the presence of four-year-old Ruttee Billimoria, a still-born child and a newborn son attest to the presence of families in that remote trading outpost. The cemetery seems to have been in use for about 76 years, from 1847 to 1923.

“At the bottom of the hill stands the “Picnic House,” a structure originally built in 1861 and possibly used as a bungli, as notes Shroff, adding, “It was later redeveloped in 1923 into a two-storey Picnic House as there were no more burials taking place there.”

From your post on Zoroastrian rites in March 27 2012, I am wondering how did you get permits from the Guangzhou Huangpu Shipping Company to go inside the shipyard to see the Parsee graves?

I went there today and was turned away at the gate for not having the relevant permit to go inside and view the Parsee buildings and graves even though I pleaded with the guard and telephoned office members inside. What s the process of obtaining permits from the shipping company or government?

Please respond: alexq316@gmail.com

https://www.tripadvisor.in/Attraction_Review-g298555-d1843666-Reviews-Foreigners_Cemetery_of_Zhugang-Guangzhou_Guangdong.html#photos;geo=298555&detail=1843666&aggregationId=101

My permit was arranged through the Indian Consulate. It’s very hard to get.

I am looking for my great-grandfather’s grave, some time in 1909. I have no idea where he was buried… in Hong Kong, Canton or Macau. Can you help please?

Thanks you.