I recently posted an exchange of letters between myself and Chris Howell, who wrote to me after reading my posts on the Mesopotamia campaign of 1915-16 in the First World War. Chris then sent me some excerpts from his book No Thankful Village: The Impact of the Great War on a Group of Somerset Villages – A Microcosm.

1

Somerset Guardian Page 16

15th May, 1914

A movement is afoot to raise a half-company of Territorials at Radstock. At present it is understood there are but four young men living in Radstock who belong to the Territorial Force, and this is not considered creditable for a place the size and population of Radstock.

2

Lt. Arthur Coombs Page 16

4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

April, 1914

Four, you say. Well, I was one of them. I’d already joined them. At that time the powers that be must have known that the war was coming and they were having great recruiting campaigns all round the country. I thought it was a good idea so I joined and was commissioned that April. My first recollection of the Terriers was years earlier when they had had a show – a field day – up at the Clandown coal pit, all dressed in their red coats.

When I joined them as an officer I knew as little as any recruit. I was 18 then, and you can imagine me, looking very young for my age and put in charge of coal miners and knowing less than they did about military matters. Sergeant Ashman used to drill the men in the field opposite Radstock Church and I joined in with them. This is us: G Company of the 4th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry – Prince Albert’s own – at Norton Hill Station that Summer. They were a grand crowd. I knew them all and where they came from and so on. And they seemed to accept me all right. They nicknamed me ‘Our Boy’! By the way, our Company had nine of the 11 in the Battalion football team. I was inside right.

3

Lt. Leslie Pollard Page 17

Indian Army

I always wanted to be a soldier – and I wanted to soldier in India. Father was then Commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Somerset Territorials and it was his view that if Mother wanted me to go, then all well and good, because he couldn’t afford to keep me in a British regiment where you had to have two or three hundred a year in order to live. All you got as a second lieutenant was five bob a day. Mother had been born in India, daughter of a Major General, so it pleased her that I should go there.

At the end of my first term at Sandhurst I was made a lance corporal and by the time I passed out I was the Senior Colour Sergeant in charge of all the cadets and all the parades. I put that down to a good upbringing in Midsomer Norton. So, I was commissioned from Sandhurst in January 1911, and left for a year’s attachment to the West Kent Regiment in Peshawar.

After my year with the West Kents I was posted to the Hasara. It was all a matter of knowing someone in order to get on – someone in Simla, someone in Delhi. My father, who was Dr George Pollard, happened to know someone – a patient – in Farrington Gurney, who had a relation commanding an Indian Battalion and so it was all arranged for me to join his battalion when I’d finished with the West Kents. And that was that.

I joined my Indian regiment at Quetta – though they had nothing to do with India, really. They were Hasarists from Afghanistan. Well, I reported to the guardroom. Second in Command was sent for. ‘See those men over there?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Go and take charge.’ A curt reception, but no more than I expected. We subalterns were a damn nuisance – conceited young men – we were bottle-washers. Well, by that time I spoke Hindustani pretty well so I went out and started talking. No reaction. They spoke Persian.

I’d been at Quetta about a year when the Battalion had orders to leave. Go out by rail for about six hours – to the end of the railway line, where the desert started. We then had 28 days’ marching out to the Persian border, averaging 20 miles a day. All over desert – there was no road. I was acting as Quartermaster at that time so I had to stay behind each morning to see each camp was cleaned up. I had a camel to catch up with the Battalion which marched steadily till it came to mid-day – luncheon time – when I would catch up with them and have breakfast and lunch togcthcr.

We were at the border for a year, stopping gun-running. There was a telegraph line which worked occasionally but no other communication except once a month when a convoy came through with stores. That’s where I found myself in 1914, when war broke out in Europe.

4

Lt. Arthur Coombs Page 33

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

9th October, 1914

After a few weeks in camp on Salisbury Plain we went to Plymouth to guard the bridges and so forth. G Company had the task of guarding Saltash Bridge for three or four days until the Special Reserve was mobilised to take over from us. While we were there, half the company was also detailed to go out with Sappers to dig trenches in case we were attacked. Well, word came back to us that our fellows were refusing to dig and the CO told me to go and sort things out. Me! A kid of eighteen! Well, I went out in fear and trembling, and luckily – well I think it was lucky – as I arrived their time was up, and they were falling in. But I still had to make enquiries and I went up to the Sapper officer who was there and it seemed that our lads, who’d only been mobilised for ten days or so, felt that it was the Sappers’ job to do the digging but they maintained that they were there to supervise the infantry. Anyway, it all ended peacefully!

People everywhere were quite convinced that it was going to be over soon and that this was the war to end wars. There’s no doubt about it. Everybody thought that. It was the general idea that it would be over by Christmas and when we were going down to Plymouth people came out and cheered us as we marched past – and the day we came away the number of girls who came to see the men off was nobody’s business.

One thing we had always been told was that we were only for Home Service, but then, in September, the Divisional General of the Wessex Division – a Major General called Donald – was called in by Kitchener and we were being asked to go abroad, to India. I’ve got his account of it here:

Towards the end of September I received a telegram saying that Lord Kitchener wanted to see me at the War Office next day. I went to the War Office and was taken into Lord Kitchener’s room, and you can imagine that I got a little bit of a shock when he said: ‘I want you to take your Division to India. Will they go?’ You must remember that at that time the Imperial obligation did not apply to the Territorials. I said, ‘Well, Sir, I do not think anybody has had much thought about it, but I am perfectly certain that if you want them to go to India they will go there right enough.’ He replied, ‘Very well, go back to your Division now, get hold of them tomorrow morning on Salisbury Plain, use your personal influence and tell them from me that I want them to go to India and that by going to India they will be performing a great Imperial duty. I have to bring white troops back from India and I must replace them there by white troops from home.’

And we were very lucky that we were sent – if we’d gone to France we’d probably all have been killed.

5

Pte. Laurence Eyres Page39

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

November, 1914

Dear Father,

We arrived in Bombay on November 9th and the following day we were allowed to land but not go outside the dockyards. Still, we found a very nice army store within the precincts and bought tea and cake and fresh butter, which were a great treat. None of us were very sorry to set foot on dry land once more, though the voyage was quite enjoyable, if long. It took 32 days.

On Wednesday we marched off the ship and onto a train. We left Bombay dock station and very soon got into the country, so saw little of Bombay. The railway carriages were a

pleasant surprise. We had expected to sleep sitting up but instead of that they put 14 of us into a carriage with seating accommodation for 46. There was loads of room for us to put our kitbags and everything and every man could lie full length on a seat.

The railway journey was intensely interesting. At all the stations of any size you could see an Englishman in charge, or rather two or three, sometimes more. Soon we were looking down 1000 feet on either side on rice fields and there was a small river running through them. That was about sunset time and the light was reflected on the river. It was exquisite.

We always got out at a station for our meals. Arrangements were made beforehand by the Indian Government and they had bread, meat, jam and tea waiting for us at various places. We went through Poonah at midnight that night and woke up to lovely scenery. We were glad of our blanket at night, and the early morning from seven to 10 was as cool as an ordinary spring morning in England.

We travelled on three railways, the Great Indian Peninsula, The Madras and Southern Manratta, and the South Indian Railway followed by a mountain railway whose name I have forgotten. We passed several troop trains on the way; they were all itching for a scuffle with the enemy after training so long. Some had fought in the Boer War or had been in South Africa or India ever since.

On Sunday morning, November 15th, we reached Metapataiyam and began our climb to Wellington. There is one mountain railway more wonderful and that is in the Himalayas, but this is supposed to be the second in the world. We climbed 5000 feet in two hours. Then at last we reached our destination after 37 hours of travelling. It is 6000 feet above the sea, and a perfect paradise . . .

6

Lt. Geoffrey Bishop Page 40,

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

May – December, 1915

I knew Laurence Eyres well – he was an extraordinary chap. I’d joined the Battalion in September 1914, when I was 17. Father was already in it, so obviously I knew G Company – largely Midsomer Norton and Radstock men – very well and a tough company they were, too. Very fine soldiers – nearly all miners. But Eyres was of a different breed. An intelligent man. A Cambridge graduate, I think. He had been going into the church. Used to say his prayers in the barrack room every night and the men obviously respected him. A lot of them used to call him Mr Eyres – but not in any way unkindly. He was in the draft I took with me to Mesopotamia.

Page 87/88

I was on detachment at Amritsar when we had a call for volunteers to go to re-inforce the 2nd Battalion of the Dorsets in Mespot. They already had a draft of one officer and 29 men

undergoing a month’s special training in Jullunder but they had an outbreak of scarlet fever there and they couldn’t go, so all the draft came from Amritsar. The Second in Command asked if I would like to go. The next day I got a signal saying that I was going.

We left about the second week in May and I took a draft of 30 men, including myself and, as I’ve already said, Private Eyres. The second draft of 15 arrived about the end of August. The official history says it was a total of 75, which is entirely wrong. Thirty and 15, according to my arithmetic, makes 45. The history books are wrong.

We got there in early June, just before the battle that was called Townshend’s Regatta. This was a largely waterborne affair in which General Townshend with a few officers and 100-odd soldiers and sailors captured the town of Al Amarah and a crack Turkish regiment – ‘The Constantinople Fire Brigade’ – as well as hundreds and hundreds of other Turkish prisoners. Townshend’s ultimate target was Baghdad and in September we captured Kut-al-Amarah for the first time in awful physical conditions. The temperature was well over 100 in the shade and the men had no water. They were totally dehydrated and exhausted. But we took Kut.

On November 22nd we again went into battle. This time it was the Battle of Ctesiphon, an indecisive to-do. It was a strange battle which was very nearly won, but in fact we didn’t owing to lack of any reserves at all. The battle was a very bloody affair with 4,500 British and Indian casualties, and not unnaturally they were largely infantry. I had six chaps in my platoon killed in about five minutes and more were killed later. There was no-one else to put in and when the Turks came back at us we retreated to Kut, a tremendously arduous march of about 120 miles, which, broadly speaking we did in about three days.

The Turks caught up with us about half way back to Kut and were given a bloody nose after which we hardly stopped. The Turks came closer and closer to us but we got back to Kut on December 5th and they arrived a day or so later. The siege had begun.

8

Lt. Arthur Coombs Page 97/98

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

February/March 1916

Our Company had been in Amritsar since late August – it was always a centre of sedition and a hot-bed of unrest and there had been riots there. We joined the rest of the Battalion here, in Peshawar, about six weeks later. Peshawar in the winter was a delightful spot. Those are the barracks in the picture. It was taken by a man called Lewis, from Bath, who was up on the roof of one of the blocks. That’s me at the tip of the Colonel’s shadow and our company is at the back. By that time we’d become a double company, commanded by the Honourable Edward Strachey.

Strachey was great man – been in the Grenadier Guards. A delightful man. All the troops loved him. We always thought ours was the best company cause we had him there and he knew what soldiering was. I always remember how he taught us to drill our men properly. There were deep drains – three or four feet deep – all around the parade ground and he’d have us out chatting about our platoon when the men were marching and suddenly he’d say, ‘Take command of the Company’. He taught us to think – and quickly!

Geoffrey Bishop is not in this picture, of course. He and his men had left Amritsar for Mesopotamia several months earlier. Theycould very well have been fighting at Ctesiphon when this was taken, before their incarceration in Kut-el-Amarah. They were beseiged there for three months from early December – in quite appalling conditions – despite two abortive attempts to get them out.

In February, 1916, we sailed up the Tigris from Karachi to Mesopotamia in an attempt to get them out. We were just under 800 strong and our Company went with B Company on Puffing Billy, the steamer in the other picture I’ve given you. There were two of them with huge barges attached to either side. We disembarked at a place called Sheik Sa’ad and set up a camp at Orah where we stayed for a day or so before setting off.

On March 7th we left Orah on a remarkable night march of about twenty miles. We must have been the leading company because I was beside Captain Strachey – who had the compass – when he was being told that he was going to guide us all out. The regulars who were with us didn’t think much of the territorials and they didn’t know that Strachey had been in the Grenadiers. One of the Staff Officers said, ‘I take it that you do know how to read a compass?’ Pompous ass. Strachey passed it to him. ‘You set it.’ But he knew perfectly well how to do it.

The march was quite an astonishing achievement – an absolutely incredible achievement – 20,000 of us, moving over unknown territory counting the turns of bicycle wheels to work out our distances. But it was completely successful, and when we arrived next morning we found ourselves in front of our objective, the Dujailah Redoubt. Ours wasn’t the first attempt to relieve Kut but this redoubt hadn’t been attacked before. Actually there were very few Turks in the trenches because for the previous few days our people had been moving English troops about on the other side of the river to make the Turks think the assault would take place there.

We had been told the brigade we were with was not to attack but that we would give covering fire when the brigade to the left of us went forward. One didn’t hear very much but from what I could gather the people on our left were either late or missed their way and didn’t attack. I think we could have gone into the redoubt with little trouble or opposition but, presumably, the place was mined so we’d have been blown up in any case.

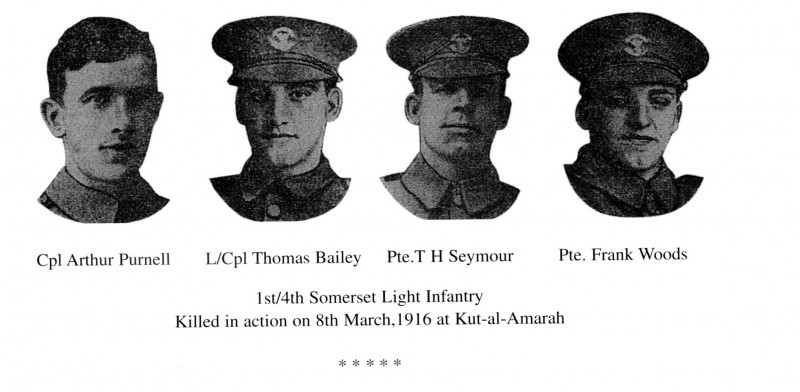

In the afternoon we had orders to move and about four o’clock we attacked, but by that time the Turks had got wind of us and were there in considerable numbers and able to drive us back. As we moved forward we found them just sitting there – waiting, and then they opened up with their rifle fire and shells. They killed three of my own platoon pretty instantly. Woods was one, he was a Midsomer Norton cricketer. Then young Bailey, another Norton man, and Seymour who was a porter on the Great Western Railway station at Radstock. I know there were at least a couple more Norton men who died.

Well, the long and the short of it was that our efforts to get into Kut failed and Townshend’s – and Geoffrey Bishop’s – awful sojourn continued.

9 Page 99

History of The Somerset Light Infantry 1914-1918

Edward Wyrall

8th March, 1916

A and B Companies of the Somersets were ordered to retire and it was during this retirement, carried out slowly and with great steadiness, that the Battalion sustained severe casualties. Captain E. Lewis had already fallen as he was gallantly leading his men to the attack. A little later 2/Lieut Lillington was also killed, (Capt. Baker had fallen earlier) In other ranks the Battalion lost, during the day’s fighting, 9 killed, 50 wounded and 4 missing. When darkness had set in the whole force was withdrawn a considerable distance from the Dujailah Redoubt to the sand-hills. The following day, after it had been ascertained that it was impossible for the force to maintain its positions, owing principally to lack of water, a further withdrawal was ordered to Orah. The 1st/4th Somersets formed part of the rear-guard, the general

retirement beginning in the early afternoon. Thus ended the Second Attempt to relieve Kut – a gallant though unsuccessful effort.

10

Lt. Geoffrey Bishop Page 99/100

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

9th March, 1916

The day after the nearly successful attempt to relieve Kut, which Arthur has told you about, the Turks sent in a flag of truce and I was told to go out and meet this chap. I suppose I was sent because I was last at school and probably spoke French better than anyone else. The fellow was riding with an orderly and had a letter from Khalil Pasha, who was the Turkish C in C. I also had an orderly and sent him in with the message and told the Turkish chap to return the next day, but he insisted on waiting. Our lines were then anything from 500 to 600 yards apart and I was out there in the middle, with him, for a couple of hours. Nice chap – a captain. He was Kahlil’s A.D.C., or one of his junior staff officers. We spoke in French and he gave me a packet of cigarettes which I hadn’t had for some time. We talked about the war and the Germans – and he didn’t go a lot on the Germans. He said his uncle had a villa on the Bosphorus and he’d like me to go and stay there after the war – that sort of thing. They were good soldiers, good fighters. Not unpleasant really.

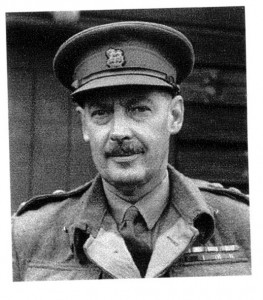

We had quite an interesting conversation with the result that the following day, when I’d

finished my report, I was seen by my Brigadier and sent in to Townshend to tell him about it. That’s his house in the picture, incidentally. I spent about an hour with him, but that was the only time I saw him. Then he sent this chap a message telling him to stuff it. However, rations were steadily being reduced and during the last few weeks we were each down to a quarter pound of bread and some horse-meat. We got relatively more and more hungry as time went on, until we were permanently hungry. Men were getting a lot of dysentery and that unpleasant deficiency disease called beri-beri.

The white flag went up on 29th April – about mid-day, I suppose it was. We went off late the following day and then the officers were taken off to Baghdad, away from the men. I was then a prisoner for the next two and a half years. Of a strength of 15,000 men, 1,800 were killed or died of disease and 1,900 were wounded. Of the 45 men I’d had with me, only four, of whom I was one, survived. The rest were all killed in action or died as P.o.W.s.

11 Page 109

Lt. Arthur Coombs

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

May, 1916

We lost a number of officers and men at Kut. And we lost more a while later at Beit Aisa, and I’ll tell you who was wounded there; a chap from Midsomer Norton called Bill Withers. His mother was a wonderful woman who ran the isolation hospital there. I well remember when Withers got hit. He knew it would mean him going home and he called out, ‘I’ve got a Blighty one!’ but unfortunately he was a cripple in a wheel chair for the rest of his life. The family had already lost another son fighting with the Somersets in France. I am given to understand that he had two other brothers – called Pharaoh and Noah. After our failed attempt on Kut we’d gone back to Basra and from there went on to Shaiba where we spent most of the summer in training and building up our numbers. One of the first officers to visit us there was Allan Thatcher, from Midsomer Norton, who was out in India with the 2nd/4th Somersets.

12 Page 109

Lt. Allan Thatcher

2nd/4th Somerset Light Infantry

May, 1916

Yes, I did join them at Shaiba – soon after their disastrous action at Kut. I’d arrived in Bombay in January ’15 and from there I’d gone down to Bangalore where we had to find detachments for different places. When war had first broken out we lived in Silva House, next door to Evelyn Waugh’s family. I knew him quite well although he was younger than we were – I remember that he used to wander round the garden in a white smock when we knew him. I knew his brother Alec better than Evelyn – I was at Sherborne with him. When I left there I studied at home for my law finals. And then war was declared and I was launched into the world.

My father had been in the 1st Battalion of the Somerset Volunteers and he thought it would be a good idea if I joined the Territorials. We went up to Borden Camp on Salisbury Plain and saw Lord Strachey who was in command and who knew my father, and I was accepted. I was commissioned on 7th October, 1914, and at the beginning of December went off to India with the 2nd/4th Somersets.

My first trip was to the Andeman Islands. There was a lot of naval activity going on there at the time and I understand that the Germans were filling up boats in Batavia – which was a convict settlement – and arming them and landing them in these islands. I went on one patrol in the islands with my platoon. Went up north on a Royal Indian Marine ship to inspect the bays to see if there had been any disturbance of the sand on the beaches. That took about six days but we found nothing. Quite a pleasant trip, though. Enjoyed it.

Another thing I did while I was with the 2nd/4th was guard the Viceroy of India for 48 hours while he was staying at Government House in Bankipur. I was in charge of an Officer’s Guard. Myself and 30 men. I had a tent in the garden of Government House. Dined with him both evenings. I didn’t have full dress uniform so I had to send for my tail coat and waistcoat and white tie to dress up for the dinner. He gave me a silver cigarette case for that duty. Still got it. It was quite an interesting thing to do. Quite interesting. I stayed with Arthur and company and the 1st/4th for a year or so, and then I joined the 10th Gurkhas in October, 1917.

13 Page 110

Somerset Guardian

9th June, 1916

Last week I published a note on behalf of some of the lads who were formerly in the G Company of Territorials and lived in Midsomer Norton, Radstock and the neighbourhood, asking that their friends at home might kindly supply them with some cigarettes. I then stated that the lads were having a rough time with little in the shape of comforts. This is pretty evident as the Captain of the Company – the Hon. Edward Strachey – could not write directly to the relatives of the men who fell in the action on March 8th because he only had one envelope in his possession. He used it to write to his mother, Lady Strachey, and enclosed in it, on bits of flimsy paper, messages he asked her to transmit to the relatives of the men who had served under him. I have seen some of these and they certainly seem to bear out my statement that the men are short of necessities, much less luxuries.

14 Page 132

Lt. Leslie Pollard

February 1917

Indian Army

I was actually at Kut when it was finally re-taken in February but I didn’t take any part in the attack. By that time I’d become a junior officer in the Signals, looking after signalling for the brigade of the 3rd Division to which I was seconded. My signalling then consisted of flags and heliograph, oil lamps and so on with some wireless thrown in. But when I started, flag waving was the main thing – semaphore and Morse – one flag for Morse and two for semaphore.

We left Basra, at the bottom of the Persian Gulf, and went up the Tigris as far as Kut. When we got there we lined up with the 3rd Lahore Division on one side of us and the 7th Meeruts on the other. As I was free from duties I was able to get my horse and rode out to a ridge where I sat and watched the troops moving about over the river. Watched the Turks disappearing from round the town and the Indian troops – Ghurkas I think they were – going in to re-occupy the place. A happier outcome to what happened when Arthur Coombs and his lot were there.

The brigade I was with then moved north and two weeks later we captured Baghdad. After that we moved on up to the Persian border where we joined up with a Russian Cavalry unit which proceeded to eat all our food.

15

Pte. Jim Peppard Page 171/172

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

Spring 1918

When we got out to Indial we were just doin’ ordinary work – guard duties, lookin’ out to

magazines an’ the like. I were a young chap an’ full o’ life, but I’ll tell you this – an’ you can tell who you like – I were a dunce, not too bad mind ‘cos I could read an’ count, but I knew out there that I ‘ad to do somethin’, an’ I did. I learnt more in the army than ever I did goin’ tuh school. There were a lad out there along wi’ me from Radstock, Jack he were called, an’ he were called to the office one day ‘cos there was an enquiry from home from his people who were worried about him – they never heard from him ‘cos he couldn’t read nor write. He should ‘ave said. I used to write home fer a couple of ‘em, Harry Hughes, the gypsy, an’ another chap.

I got on all right out there an’ I used to like to treat everybody else right, don’t matter if they were black or white or yellow, but some of our boys used to really lay into those Indian fellows tuh make ‘em clean their kit. That used tuh make I wild. Thass not the way tuh treat anybody. I always got on very well wi’ ‘em, they’d do anythin fer me. All’s I had tuh do was take my equipment off – boots or anythin’ – an’ put it down, an’ there was one of them would come to see if I wanted it done. He’d clean my drill, blanco, do all me buttons – I never had tuh do anythin’. An’ d’you know how much I did give’n a week? Four annas – fourpence a week.

Mind you, none of us had much to spend out there an’ I certainly didn’t. When my sister’s ‘usband were killed up at Emborough quarry she were left wi’ a little girl an’ no compensation – nothin’ whatsoever – an’ when I wen’ in the army I allowed half my money to her – that were three an’ sixpence each week – an’ I had the rest to play with. She ‘ad that all the time I were away. It were a close family we ‘ad.

There you are, thass us, G?Company out in Wellington Barracks, in Indial. We’m a smart lot, ain’t we! See Mr Coombs? The officer sitting there by Captain Strachey – on the left. This other photo is yours truly, 203853 Private Peppard, J. 1st/4th S.L.I. Old Jim out in Indial. Yeah. I borrowed the uniform fer tuh have me photo took – that were the Somersets’ Regulars’ peace time suit – an’ I had those two pictures of Father an’ Mother put in those hearts up in the corners. Don’t you think my Agnes picked a nice boy?

16

Somerset Guardian Page 173

8th March, 1918

STATION MASTER OF BAGHDAD

A Wellow porter, Sgt Albert Pritchard, Somerset Light Infantry, mentioned in General Sir Stanley Maude’s Mesopotamia De spatch, is Station Master of Baghdad. He was a porter on the Somerset and Dorset Railway at Wellow station and went to India with the 1st/4th Somersets.

17

Pte. Jim Peppard Page 201

1st/4th Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry

October, 1918

I stayed out in India on general duties. Poonah, it were. Then I got taken ill. I led out on the sand an’ thought I were gonna die. They said t’were a touch o’ cholera, or sim’lar the same – an’ they sent me up in the hills to Wellington, for convalescence. We did go up the mountain in an engine on cogs – ever so steep, an’ when we got to the top we could look down an’ see the cattle an’ that, ever so small, down on the plain. T’were beautiful. I must have stayed there two or three months an’ I got back to the depot the same afternoon as our lads left in the morning fer Russia – what fer I could never find out. But I found out that Maurice Baber had been transferred to the ’Ampshires then were taken ill an’ died. There he sittin’ alongside me in the picture there. He were always so healthy.

18

Captain Arthur Coombs Page 210

1st/4th Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry

1919

In Mesopotamia we didn’t know when we were going to get home and the rules came that the men would be returned as they were needed. The coal miners went off first, then various other people – students and things like that – and I, being nothing, stayed to the last with about 50 others. I found myself in charge of the cadre coming home on the troopship. There was a fog in the Channel so we were two hours late getting into Bath Station – at eight in the evening instead of six.

There were absolute crowds there to greet us and all of the people who had been out in India with us had paraded to meet us. I think the whole of Bath must have turned out to line the streets. I’ve never seen such masses. The police made a passage for us to get through the crowds and I gave the order to march, but then I turned round and there was only a young lieutenant and the C.S.M. behind me – nobody else. The crowd had scuppered them. Well, the police formed a rugby scrum and we got the men up to the Y.M.C.A. where they were taken care of. We were then taken to the Fernley Hotel. It was eleven at night by then, and the first thing I did was to order a whisky. ‘Very sorry, Sir. This is a teetotal hotel.’ I have never found out who was responsible for that.

19

Epilogue

Geoffrey Bishop Page 214/215

‘Like his father who was a doctor – and in the 4th Somersets before the war – Geoffrey decided that he would become one too, so he went off to Bristol University and the Bristol Royal Infirmary to qualify. He then became a country doctor and practiced in Shepton Mallet for the whole of his career with the exception World War Two. He always stayed with the Somersets and was commanding them when war broke out. He spent the first year of the war with them in England up until the call came for him to stop playing soldiers and join the RAMC.

He served with them in forward Casualty Clearing Stations in North Africa and Italy, and was eventually made up to full Colonel with a staff job in the Area High Command, near Salerno – which is where I was serving as a Red Cross Welfare Officer, and where I met him. We moved here to Bath when he retired in 1964. Geoffrey died in 1987.’ (Sheila Bishop)

21

Arthur Coombs Page 216

In 1920 I went out to the tea and rubber plantations in Ceylon. Stayed for 32 years. At one point I was running a tea plantation and someone commented that I was far too young to be in charge. I was 38! It was pointed out that I’d been a major in the last war – which I was for a while, standing in for someone for a couple of months. When I retired I came to Bath to live and I now lunch every Wednesday and Friday with Geoffrey Bishop. Once a year those of us who are left from the 1st/4th get together for our Braemar Association dinner. We had a good crowd once: Cox and Nifton and Openshaw – the doctor’s son from Cheddar – Clutterbuck, Willie Moger, Humphrey Tanner who was Frome – Butler and Tanner, you know – he was wounded out there, as was Sir Charles Miles. Lewis, whose father ran the paper in Bath – he was also wounded. Worger from Radstock always came. Charey died last year. Stourman – he’s dead. Not everyone made it back of course: Baker, of Weston super Mare, and Lillington from Shepton Mallet, and the other Lewis were all killed out there. Only a few of us left now. Only a few.

22

Jim Peppard Page 218

My nerves went after the war – absolutely gone. An’ that wen’ on fer two year. I got so low. I just wanted to be on me own – didn’t want to see nobody. Go in the garden. Hide. Once I’d got over that I learnt the mason’s trade. I told you how I volunteered fer everything during the first war, well I done the same in the second. First thing I done was build a hostel for land workers on Bodmin, then I went in to Bath to clean up fer the blitz, same in Bristol and then t’were London – I were up there when the first two rockets come over, in Forest Hill and the building I were in copped it. You never seen such a mess. But I’ve always been the lucky one. It’s bin a good life!’

23

Leslie Pollard Page 219

‘He stayed in India for the whole of his military career and retired as a Brigadier in 1939 (did you know, the Indian Army’s Corps of Signals still holds its reunions at the Pollard Arena in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh). At the outbreak of WWII he went back into uniform as Commandant of Catterick Camp, the garrison town in Yorkshire. After that war he and his wife Patricia then settled here in Stone Allerton with the Brigadier’s batman, MacDonald, and their much loved Jersey house-cow, Jemima. He died in 1983.’ (Joan Stevens)