In January 2003 I accompanied an expedition that was conducting a survey of river dolphins on a stretch of the Mekong River in Cambodia. The expedition was led by Isabel Beasley, who was then a young research scholar specializing on Orcaella brevirostris: also known as the ‘Irrawaddy Dolphin’ this species is found in many Asian river systems and deltas (including of course, the Sundarbans, which is why it figures prominently in The Hungry Tide).

A New Zealander by birth, Isabel Beasley was a student of the eminent Australian cetologist Helene Marsh: she got her Ph.D. a few years later and is now one of the world’s leading authorities on river dolphins.

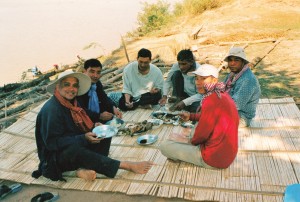

The expedition consisted of some half-dozen people, including Isabel, myself, and a few Cambodian researchers and boatmen.  Traveling in a narrow skiff, we made our way upriver to the border of Laos, from Kratie (pronounced Kra-cheh), a sleepy, picturesque little town in eastern Cambodia. From sunrise to sunset we watched the river, and at night we slept in small riverside hamlets.

Traveling in a narrow skiff, we made our way upriver to the border of Laos, from Kratie (pronounced Kra-cheh), a sleepy, picturesque little town in eastern Cambodia. From sunrise to sunset we watched the river, and at night we slept in small riverside hamlets.

It was an extraordinary experience, and, as is my habit, I kept a journal. Here is an excerpt from the entry for:

January 9, 2003.

I’m writing this as we slowly make our way through a series of ‘rapids’. The current seems very fast, and in places the water is turbulent – but apart from that the principal indication of the rocks below consists of bushes: we seem to be moving through a kind of swamp, with the whole width of the river’s surface broken by bushes. It would not be possible to cross the rapids in this season in most years, but this year the water is said to be exceptionally high. This is the reason why there are so few dolphins to be seen. Yesterday we went through four major ‘pools’ without seeing a single dolphin. From Isabel’s point of view this is very significant – because if the dolphins aren’t here, where are they? I told her that I was certain that a great discovery would be occasioned by this question. She said: ‘I hope I’m not in my sixties before I can answer it.’

The rapids extended over a mile and we are now past them, back on open water. Soon after that we stopped for lunch, at a fishing village – where they’d just caught some river fish which (Mr. Somani said) were a great delicacy. We climbed up the banks into the village, and the villagers lit a fire on which our team roasted several fish. This, along with the packets of food we’d brought from Kratie, was our lunch.

Isabel – who doesn’t eat much apart from instant noodles and Ovaltine (anything from a packet) – looked quite sick and went away for a walk. But Mr Seng Kim, Mr Somani and I talked about many things.

After lunch, Isabel went to interview the old man of the village, taking Mr Somani along to translate. I tagged along. The old man was small and bandy-legged, with a face as wizened as a walnut. He said that in the past there were dolphins a long way up the river, but the numbers have steadily fallen. His feeling was that fishing with bombs and ‘elastic fishing’ were principally responsible for the decline. Vietnamese soldiers, in the 1979-80 period, he said, were responsible for killing a lot of fish and dolphins with bombs. Before that American bombs had also taken a heavy toll (several other villages said that American B-52s had bombed that area heavily during the war). He also said that though dolphins were never seen in his area now, he remembered seeing them when the Japanese were in the village (during the Second World War). At that time, he said, otters and elephants were also seen in these parts – but these too had not been seen there for a very long time. During the ‘Pol Pot regime’ he said, he had been sent to live in Sampot. Why? He couldn’t really think of an answer.