On Sunday June 17, the democracy movement in Myanmar lost one of its pillars, Ludu U Sein Wein.

Ludu U Sein Win was a writer, journalist, political activist and teacher. He ran a school that played a significant part in keeping the country’s intellectual and literary traditions alive through the darkest years of military rule.

U Sein Win was from a prominent literary family of leftist political leanings (‘Ludu’ is a honorific reference to a famous Burmese journal). He was arrested in 1967 and spent many years in prison, some of them in the infamous Coco Island. For two years he was in solitary confinement. His cell measured 10 feet by 12 feet and he had no books – nothing but a mat and one blanket. Every day he would walk 20,000 steps in that cell. Counting his steps helped him control his mind. He was released in 1978 when a new constitution and a general amnesty were announced, but was detained again in 1980. While in prison, he had a stroke that left his right side paralyzed. Through all this he was never tried or charged. He had broken no law – his political views were his only offence.

‘The incredible thing about the Burmese people,’ he said to me once, ‘is that we have learned to survive all this and more.’ There was not a trace of bitterness in U Sein Win although there was plenty of outrage and anger. He exuded kindness and decency and was beloved by everyone who knew him.

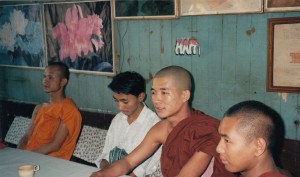

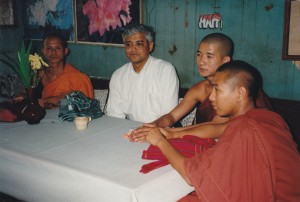

U Sein Win was released in 1981 and in the following year he founded the ‘Feeling, Mood and Action School’: it was nominally a language school and existed for the purpose of teaching English. I visited it several times in 1995 and 1996, and spoke at great length with Ludu U Sein Win. Below are some of my notes from those conversations, along with some of the pictures I took during my visits.

The Feeling, Mood and Action School runs from 9 to 5 every day. There are no holidays – it is open on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays. There is no curriculum and U Sein Wein is the only teacher. He lectures on everything – business, politics, art. Students can come and go as they please. The only rule is that they are not allowed to utter a single word in Burmese – only English. The basis of the school is argument; he teaches his students to argue against established notions.

‘I am not teaching,’ he says, ‘just speaking, developing their minds, their mental powers.’

The school is necessary, he says, because in Burma even those who have graduate degrees in English cannot use the language. In Burma from a very young age, ‘young people are trained to obey their superiors – parents, teachers, the government.’ The Burmese educational system encourages rote learning. Students have no opportunity to think. There are no textbooks because the govt can’t provide textbooks to every student. They learn from notes written by teachers.

‘They have trained our youth like animals from a circus. People don’t know how to think.’

Many of his students have romantic problems because of family pressures. When they tell him about their troubles he says; ‘Look to your conscience.’

‘Especially in our Oriental society we are trained to obey our parents. The military takes advantage of this mentality of obedience.’

A course at his school costs 1000 Kyat – it doesn’t matter whether the student attends for one year or ten. ‘It’s like a club with life membership.’ He has two or three hundred students; doesn’t accept anyone who is not recommended by a former student.

It’s very hard to get in – 10 or 20 applicants come every day. They beg him to let them in, some even offer money. He has all kinds of students. Some are drug addicts, some are the problem children of rich families. He accepts them and they change. Even the junta sends him their children. His old students shower him with gifts (looking around I notice that the room is filled with all kinds of gifts – electronics, flowers…).

The reason he founded the school was to train young people to think freely, to think bravely, to do the right thing no matter how much they might have to suffer.

In his school everything is discussed. Even businessmen and military officers speak their minds about the junta. But they also talk about international affairs, movies, songs, novels – but only in English.

In his school everything is discussed. Even businessmen and military officers speak their minds about the junta. But they also talk about international affairs, movies, songs, novels – but only in English.

The junta knows what goes on inside, but they haven’t interfered so far.

‘Only Aung San Suu Kyi can lead the country out of the quagmire it is in.

‘Other politicians have been killed; there is no one left. But she is like her father, she is not a politician, she doesn’t do any ‘politicking’. She always speaks her feelings and tells the truth.’

He laughed. ‘In a democracy maybe she would not be elected.’

Loved reading about Ludu and the glimpse it gives into working of Myanmar junta regime!

Thank you for sharing this. It always gives me a shiver when I read in the acknowledgements to the Glass Palace that a number of people in Burma had better not to be acknowledged for fear of reprisals. I understand Ludu U Sein Win is one of these people. I had also been thinking that Dinu’s school of photography was just a clever invention: how could I be so naive?

“I know your website from Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB).As i am a student of IGCSE.I want scholarship to foreign countries for attending medical school. Please give advice and you can contact me again.”

Thank you for all.