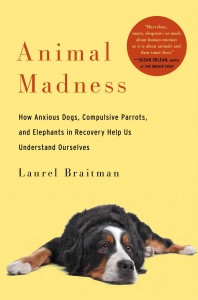

Animal Madness: How Anxious Dogs, Compulsive Parrots and Elephants in Recovery Help Us Understand Ourselves

Laurel Braitman

Simon & Schuster

[to be published June 10, 2014]

Rare indeed is it to come upon a work of non-fiction as compelling as Laurel Braitman’s Animal Madness.

The book is in part a memoir of the writer’s evolving relationship with animals: at its heart is the story of Oliver, a pet dog. Oliver is a Bernese Mountain Dog: ‘Bred to guard livestock and pull carts of cheese and milk through the Swiss Alps, Berners are handsome, broad, and regal, with an air of accessible friendship.’

Berners are very desirable but also very expensive; unable to afford a puppy Laurel and her then husband decide to adopt an adult dog at the suggestion of a vet. ‘[Oliver] carried his white-tipped tail like a flag raised high and arching over his back. His white paws were lion-like, huge and spreading, and his coat glossy and feathered like a 1970s haircut.’

They adopt the dog on impulse: ‘We’d fallen for Oliver at first sight. It felt more like a physical sensation than a conscious decision. It certainly wasn’t rational. We brought him home that same afternoon.’

But soon enough they realize that they should have asked a few questions.

‘The first real sign of trouble I discovered by accident… I said goodbye to Oliver and locked the house, only to realize as soon as I reached my car that I’d left the keys in our apartment. As I headed back up the block to our building I heard a plaintive yowling – not feline nor human … it was a bark that shounded like the squeak of an animal too large to squeak (this was before I knew any elephants), and it was coming from our apartment.’

It turns out that Oliver’s behaviour is very much like that of human being who is possessed by uncontrollable anxieties. ‘If we didn’t return home by five or six in the evening, we knew he would have destroyed pillows and towels or chewed on wooden moldings. He scratched so hard at our floorboards that it looked as if we lived with giant termites… If we were with him… Oliver was the picture of calm. Alone he was a tornado.’

But things get worse.

‘On a warm May afternoon in 2003, a little boy I’d never met was doing his homework in the sunroom off his family’s kitchen in Mount Pleasant, a leafy neighbourhood in Washington, D.C. The back of our apartment building faced the boy’s house, and as he worked, he looked out to the row of urban yards along the alley, separated by chain link or small planks of sagging wooden fencing, dotted with trash cans. He happeneed to look up that Saturday just as Oliver … jumped through the kitchen window of our fourth-floor apartment.

‘No one had seen Oliver at the window, even though it had to have taken him a long time to push the air-conditioning unit out of the way and rip a hole through the wire mesh of the screen that was big enough for his 120-pound body to fit through. The pet sitter that we’d left him with had gone to the farmer’s market, leaving Oliver by himself for two hours. He must have begun to slash and chew through the screen as soon as he realized he was alone. Once he made the hole large enough, Oliver hauled himself through the opening, more than fifty feet above the ground.

‘‘Mom!’ the boy screamed, ‘a dog fell out of the sky’.’

Oliver survives the fall and lives on for another two years, during which time his owners desperately seek treatment for him, from many different experts. But to no avail; one day, after working himself into a panic Oliver chews and swallows so much wood that he gives himself an awful case of bloat – ‘a horrid and probably excruciatingly painful predicament’. The attack is so bad that he has to be put down.

Oliver’s death changes Laurel’s life: ‘We divorced the year after Oliver died, and a few years after that he stopped taking my calls. I can’t say that we broke up because of what happened with Oliver. That would be a lie, or at least it wouldn’t be the whole truth. I do believe however, that if Oliver had lived, we may not have broken up when we did. Dogs have a way of gluing people together, even ones who are already coming unglued.

‘Now it feels like I walk around with a few different drafty spaces in my chest. One is in the shape of a dog, and there’s at least one more in the shape of a man. And in the years since Oliver died, I’ve fallen in love again anyway – with a half dozen elephants, a few elephant seals, a troop of gorillas, one young whale, a couple of long-dead squirrels, and a handful of men and women who came into my life as if they’d been tugged there by invisible leashes… Losses and disappointment can do that if you’re lucky. Before you know it your pain has welcomed the world. That’s what happened to me anyway. One anxious dog brought me the entire animal kingdom. I owe him everything.’

Could it be said that Oliver’s afflictions were ‘emotional’ or ‘mental’? The intellectual core of the book consists of a quest for an answer to this question.

The difference between a ‘happy’ dog and an ‘angry’ one is perfectly apparent to most human beings. But to ascribe emotions to animals is to affront one of the foundational tenets of Enlightenment thought. This is how Laurel puts it: ‘In 1649, the French philosopher René Descartes argued that animals were automatons, lacking feeling and self-awareness and operating unconsciously, like living machines. For Descartes and many other philosophers, capacities for self-consciousness and feeling were the sole province of humanity, the rational and moral tethers that tied humans to God and proved we were made in his image. This idea of animal machines proved to be sturdy and enduring, revisited time and again for hundreds of years to prop up arguments for humanity’s superior intelligence, reasoning, morality, and more. Well into the twentieth century, identifying human-like emotions or consciousness in other animals tended to be seen as childish or irrational.’

Not every scientist subscribed to this view. Darwin for one took a very different position. In 1872 he published On the Epression of the Emotions in Man and Animals; here, as elsewhere, he argued ‘that humans were just another kind of animal. He believed that the similar emotional experiences of people and other creatures, such as sad chimps, dejected dogs, or happy horses, further demonstrated the existence of our shared animal ancestors.’

But in this matter at least Darwin was in a minority among scientists. For a long time the attribution of a mind or consciousness to animals and plants was anathema in the sciences as well as the humanities (in the latter it could even be said that the matter is pre-judged by the very word, which in itself defines a boundary between the human and all else).

Today there are few in either the sciences or the humanities who would perhaps openly confess to subscribing to the Cartesian notion of animal as automaton. Yet, in practice, as Laurel points out, a mechanistic view of the non-human world is often institutionalized in a different doctrine – one that anathemizes anthropomorphism (i.e. ‘the projection of human emotions, characteristics, and desires onto nonhuman beings or things).

‘Like a heavy leash that drags along behind nearly all twentieth-century efforts to understand the emotional lives of other animals, anthropomorphism has tended to be resented and feared. Radical behaviourists like B.F.Skinner, comparative psychologists, ecologists, and many ethologists warned against sentimentalizing other animals and rejected Darwin’s ideas on animal emotions, working to suppress what they considered subpar science. For a long time anthropomorphism was a dirty word in the behavioural sciences, despite the fact that experimental animals were busy acting as models for human psychobiological phenomena inside laboratories worldwide.’

Fortunately things have changed: ‘In many ways the past forty to fifty years of research on animal emotion and behavior represents a long, slow, scientific U-turn back to Darwin and his arguments on the shared nature of emotional experience.’ There is now a great wealth of research into animal ‘consciousness’ and Laurel (who has a PhD in the history of science from MIT) provides us with some fascinating glimpses of this rapidly-expanding body of work. In the process it becomes clear that not only do animals suffer from many of the mental and emotional disorders that afflict human beings – anxiety, depression and so on – but they also respond in similar ways to medication. Indeed, most of the psychotropic drugs that are now prescribed for human beings were first tested on animals. ‘You could argue,’ Laurel writes, ‘that this is not the story of animals taking human drugs but of humans taking animal drugs. Almost all of the contemporary psychopharmaceuticals – from antipsychotic drugs like Thorazine to minor tranquilizers like Valium to the antidepressants – were developed in the mid-twentieth century, and animals were test subjects from the very beginning.’ This is of course, nothing short of a ‘tacit acknowledgement of emotional (and neurochemical) parallels between humans and other animals.’

Laurel also presents plenty of material to suggest that like human beings, animals can hate, forgive, grieve, despair – and even commit suicide. But is it possible to say that these words, when used of animals, refer to an exact counterpart of what they refer to in human beings? Of course not. For that matter it isn’t possible to say that psychic states are exactly the same in different human cultures – or even in different people.

This is how Laurel sums up her own position: ‘all human thinking about animals is, in some sense, anthropomorphic since we’re the ones doing the thinking. The challenge is to anthropomorphize well… this means avoiding anthropocentrism: the belief that humans are unique in our abilities and that our intelligence is the only one that counts.’

Animal Madness is compulsively readable and thoroughly engaging: Laurel has the rare gift of being able to combine ideas, research and personal experience into a compelling narrative. Yet behind the engaging tone and the lightness of touch there is a deep seriousness, as indeed there should be. For the ideas that animate Animal Madness are of the greatest urgency and importance, especially in this era of climate change: to acknowledge that all living things exist within a continuum of consciousness is a vital first step towards the dissolution of that human-centred world view that has, ironically, led humanity as well as millions of other species to the brink of disaster.

There was a time, many years ago, when I used to conduct occasional seminars at Harvard. In the process I met many talented young writers – several have since gone on to write successful and highly-regarded books. Laurel Braitman was among the most gifted of that group: I never doubted that she would write an exceptional book some day. And so she has – may it be the first of many!