[The text and photographs below were sent to me by Santanu Das: they are posted here with his permission.]

Of all the colonies of the European empires, British India contributed the highest number of men, estimated around one and half million men (including both combatants and non-combatants) to the First World War.

‘This is not war, this is the ending of the world’ wrote an Indian sepoy from France.

In a grotesque reversal of Joseph Conrad’s vision, over a million Indians were voyaging between 1914 and 1918 to the heart of whiteness and beyond – Mesopotamia, Egypt, Palestine and East Africa – to witness ‘the horror, the horror’ of Western warfare.

What were the responses to the war in India? How were the Indian troops perceived in Europe and in Mesopotamia?

Above all, what were the experiences and emotions of these sepoys as they encountered new countries, new people, and romance as well as new forms of killing?

Based on archival research in several countries, India, Empire and First World War Culture aims to at once recover and examine Indian war experience and literature:

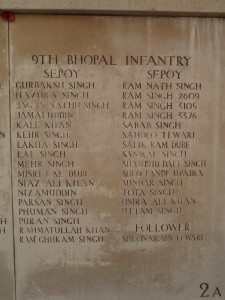

the lives, stories and writings of the soldiers, the ways they were represented in the literary and cultural consciousness of the time, both in Europe and British India, and the relation of the war experience to nationalism, decolonisation and present-day memory.

It unearths a variety of fresh material from and beyond the archives

– from letters, diaries and memoirs by sepoys and army doctors to sound-recordings of Indian POWs held in Germany to photographs, sketches and films held in various collections to trench objects and memorabilia found in Belgian battlefields and French farmyards.

My twin aim in this book is to uncover and understand the private tremulous world of the Indian sepoy as well as to embed the memory of the First World War in a more international and multiracial framework.

Just a minor correction to an otherwise great article – India was not a colony of Great Britain. It was an Empire and the only possession accorded that status. I can’t find a reference but the point was made in one of those BBC historic series about the history of India. When India got independence, the King George coins lost the “Ind. Imp.” inscription forever. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Raj