Rarely has a novel seemed as timely as Tabish Khair’s Jihadi Jane.[i] As the title implies, this is the story of a radicalized young British-Muslim woman who goes to Syria to join the jihad. The narrative is presented as a first-hand account, recounted to the writer by the protagonist, Jamilla. The form is ingenious: it circumvents all the problems of plausibility that such a project might otherwise have entailed.

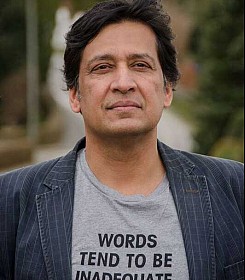

The setting of the novel is not so much Syria as England, the country in which its principal characters have come of age: the experience of Muslim immigrants in Europe is thus central to it. This is familiar territory for Tabish, who is of Indian-Muslim background and has long been a resident of Denmark where he teaches at the University of Aarhus (I should add that I have known Tabish for many years and have written the foreword for an anthology that he co-edited).

But to be an European of Muslim heritage is not necessarily to possess an understanding of the motivations and aims of those who have joined the conflict in Syria: contemporary jihadism is, after all, a cult-like phenomenon that is very distant from the lives of the great majority of European Muslims. If the novels brims with convincing detail – which it does – it is clearly because a great deal of research has gone into it.

Yet it isn’t research but an aspect of Tabish’s lived experience that is the source of his most important insights into the phenomenon of jihadism. As a teacher himself he grasps, as few have done, that the processes of studying and reading, and the successes and failures of various forms of pedagogy, are central to contemporary fundamentalism (the word Taliban is, after all, the plural of talib, ‘student’).

Jamilla’s journey to Syria begins in school, and a teacher of literature plays an especially significant role in it. The teacher in question is ‘an Indian woman called Mrs Chatterji’ who ‘loved English and English poetry with the sort of fanaticism that only the ex-colonized bring to both.’

Jamilla finds Mrs Chatterji, with her love of literature and her woolly-minded liberalism, utterly ludicrous. Their differences are brought to a head by a poem (Wendy Cope’s Reading Scheme): ‘a dexterous poem,’ Jamilla says of it, ‘using a reading scheme to talk humorously about a suburban mum having an affair with the milkman and being discovered by the husband, all of it narrated through the perspective of her two small children.’

Although Jamilla is perfectly capable of appreciating the poem’s technical virtues she is irked by its content. She responds to Mrs Chatterji’s praise of its cleverness and humour by breaking into the North England dialect which is, effectively, her native language: ‘Maybe ‘tis funny to you… I’ll say ‘tis an obscene poem, ‘tis ‘bout a sin me God forbids. ‘Bout ‘dultery. ‘Raight? That’s nowt to use for cheap laughter.’

Taken aback Mrs Chatterji asks Jamilla to write an essay on the poem. She obeys, and as she writes ‘an ocean of pure vehemence’ wells up in her, ‘anger that seemed to come from beyond me, which left me feeling angrier still.’

Mrs Chatterji’s well-intentioned liberalism proves no match for the certainty of Jamilla’s conclusions: ‘Reading Scheme’ was a depraved poem about adultery, and in this it reflected the depravity of the West, which had long gone against the will of God…’

Mrs Chatterji’s face grows pale as she reads the essay and ‘at the end the papers almost slipped out of her hands. I believe she had to steady herself by leaning with an arm on her desk. Then she said to me, ‘But Jamilla, I don’t think you get the poem; it is not about morality or God; it is, it is about…’ She could not say what it was about. She repeated weakly, ‘I don’t think you get it.’

Jamilla’s victory, and her confirmation in her beliefs, is doubly assured when her family is summoned to a meeting with her teachers. They send her brother to the school and far from admonishing Jamilla he gives the headmaster and Mrs Chatterji an even ‘more emphatic rendering’ of her position, calling for a ‘blanket ban on such poems in school.’ Mrs Chatterji’s defeat is complete.

Although this episode is written in a near-comical vein, it is a powerful commentary on some of the failures of contemporary liberalism, perhaps most significantly its inability to challenge certain values and ideas largely because of a well-intentioned unwillingness to offend. But this is, in turn, an extension of the kind of ‘multi-culturalism’ that has long been practised by some Western governments, whereby state patronage is directed towards conservative religious groups because they, and not their secular counterparts, are thought to be more authentically representative of migrant populations.

Jamilla’s victory over her hapless English teacher serves to strengthen her growing convictions and she becomes increasingly focused on narrow readings of religious texts. In this she finds powerful reinforcement on the Net which by its very nature tends to reduce complex bodies of thought to simple, easily comprehensible formulae. The kind of thinking that results is typified by a fighter whom Jamilla encounters in Syria: ‘His was almost a technological Islam, its pruned rituals as shorn of ambiguity as a hammer or a computer code… It was a do-it-yourself manual – and he had many of those too, on repairing motorcycles, preparing bombs, assembling guns, electricity, carpentry… They were all short, concise, to the point, concerned not with theory but with application, not with thought but with practice.’

Muslim radicals are by no means alone in practising these instrumental methods of reading: in other religions too, including Hinduism, texts are now increasingly being read as though they were workbooks, couched in language so transparent as to be unaltered by translation. To approach complex theological documents in this way is of course a travesty of textual exegesis as it was once practised. In the past, in all religious traditions, an extensive knowledge of languages and many years of rigorous study were required in order to expound on sacred texts. Most of us simply do not have the skills to read and understand these texts and the traditions of commentary within which they are embedded: in no religion, historically, were believers encouraged to pick up their scriptures and start reading them as if they were self-explanatory. This began at a specific moment: with the Protestant Reformation. Those who decry the lack of a similar reformation in the Islamic tradition need to understand that what the world is now dealing with is the fallout of exactly such a process.

As a teacher himself Tabish understands intuitively both the mysterious power of pedagogy and the nihilism that can result from its failures. This makes Jihadi Jane a uniquely insightful account of a phenomenon that, for most of us, almost defies comprehension. Although Tabish is careful not to condescend to his principal characters his critique of their ideology and motivations is all the more powerful because he fully understands how much at odds they are with the beliefs and practices of the great majority of the world’s Muslims.

This powerful, compelling, urgent novel succeeds in being compassionate towards its principal characters without flinching from the full horror of their choices.

Amitav Ghosh

[i] Penguin India, 2016; to be published elsewhere as Just Another Jihadi Jane.

It is an honour to get such a positive review by you. I must also add that it feels particularly good because you commented on the form of the narrative and the implicit historical aspects of my reading of religious fundamentalism today, for instance by highlighting the ‘Protestant’ connection. I had worked much on these aspects — to integrate them into a novel, without reducing it as a novel. Thank you.

Beautifully written. Minds Interpret according to very much people’s own thinking. The girl had made up her mind about her beliefs so Mrs Chatterjee’s poem is irrelevant to her ………