I cannot remember the date of my marching out of Tamu, it was like any other.

My departure having been delayed considerably because of the dogs, I managed to crawl into Palel around midnight and slept the sleep of the ‘innocent’ under a large banyan. Being high ground the night was cool and my light woollen jersey came in handy. Since I was expecting the Agent within the next two days, I made a round of the open-air camps which had cropped up all round the small town and found a perceptible change of mood – from tired sullenness to a more cheerful and hopeful frame of mind.

The Agent reached Palel by jeep, from Imphal, that evening and after a snack meal of green tea and Manipuri rice and curry we decided to sleep in the open. However, it turned quite chill by ten p.m. and having nothing to cover ourselves with, we decided to crawl under an Army truck which was still pretty warm after a run from Dimapur. We slept well but the morning brought a shock. The Agent took one look at me and burst into a roar of laughter which was heartily reciprocated from my end. We discovered to our mutual satisfaction that a drippy oil sump had covered us both in sticky oil from head to foot and even with a dip in a nearby stream and much scrubbing with a small piece of soap which we shared, a sticky mess continued to cling to our arms, face and head. It required major effort later, to get rid of the oily mess. There was nothing one could do about the clothes and they continued to adorn our bodies.

The Agent stopped over at Palel for the day which we utilised for detailed planning of our functioning from Palel to Dimapur Via Imphal and Kohima.

The Agent stopped over at Palel for the day which we utilised for detailed planning of our functioning from Palel to Dimapur Via Imphal and Kohima.

He had received instructions from Delhi to return to the Capital earliest feasible and it was evident that the Government would want to know in some detail not only regarding conditions and events up to Tamu but particularly so regarding volume of refugees crossing over into Indian territory/ casualties, status of food stocks at various Camps, sanitation, transport facilities for women and children, sick and injured along the 160 miles of hilly track connecting Tamu-Palel-Imphal-Kohima-Dimapur.

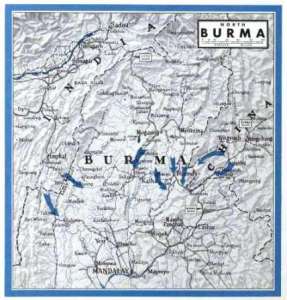

He made copious notes of my experience thus far – from Mandalay-Monywa-Kalewa-Tamu on the Burma side linking up with the newly laid Military road from Tamu onwards on the Indian side.

However, there was one issue on which we thought differently; should the refugees be kept moving on a day-to-day basis or in any case without loss of time or should they be encouraged to stop longer at the Camps in order to ensure (1) Recoupment of physical condition and morale, and (2) exercise of regulatory control on the Palel-Dimapur stretch in order to be able to make maximum use of the military vehicles for previously mentioned categories, and have planned release of refugees from the various Camps after a 2-day rest. This would also make it easier for the interim Camps to adjust more easily to the daily inflow. My most important argument in favour of this plan was the fact that un-controlled influx of refugees into Dimapur would impose an impossible burden on the small township and the single line rail service from Dimapur to Calcutta involving two longish river crossing by railway ferry steamers, could also be subjected to severe strain with tragic possibilities.

The Agent too had a cogent reason in favour of fast clearance of refugees from Manipur and that was the imminent on-set of the S.W. Monsoon which could create the most adverse conditions for transit of refugees from camp to camp creating major health and hygiene problems. We had also to bear in mind that the road was still ‘kutcha’ and though well laid and maintained by Army Engineers it was subject to land slides blocking traffic for longish periods of time. This would lead to accumulation of refugees at intermediate points quite unprepared for servicing them and so on. He had evidently discussed the matter at a higher level both in Delhi and with local military and civil authorities who in their wisdom had whole-heartedly supported the first option.

After our comprehensive and frank exchange of ideas he decided to leave immediately for Imphal for a review of the problem and consideration of available options with all concerned and earliest possible departure for Delhi where a final decision would be taken. It was also decided that I should stay back a couple of days at Palel in order to get a clearer idea of the size of residual streams still crossing the border. He left for Imphal that afternoon in an Army jeep and I decided to go along with him to a Camp some 5 miles up the road towards Imphal to see if it would be feasible to take the pressure off Palel by persuading the refugees to do a further 5 miles thus reducing the next day’s march.

The conditions at the Camp were satisfactory and it was agreed that it could easily accommodate 5,000 instead of the 1,000 envisaged earlier, with minor additions to available facilities. By the time I returned to Palel it was well after sundown and that night as also the two subsequent ones were spent in relative comfort in one of the Dak Bungalow rooms, which had suddenly become available with the chowkidar raising an excellent meal for my sole benefit. I discovered that this sudden glow of goodwill had also seeped into the consciousness of the skeleton Police and Civil staff who reacted in typical fashion ignoring the fact that hardly 24 hours earlier even my request for ‘verandah’ accommodation had been summarily turned down and the young Inspector of Police had refused to accept my identification for discussing certain minor law and order problems which cropped up between the refugees and locals.

I made no issue of the matter and received maximum cooperation from them all till the time I left. The two days went fast enough and on the third I set off for Imphal on the dot of five in the morning. The weather was pleasant and the road not much crowded at that time of day. With just a couple of short breaks I managed to cover the 30 miles in 12 hours reaching Imphal at around five in the evening. The main Camp at which I landed up was a large sprawling complex covering approximately 5 acres almost in the middle of the Town with ‘basha’ accommodation for about 5,000 – any overflow to be either accommodated in the open or diverted to other Camps on the periphery of the Town. The Anglo-Indian lady in charge, a large middle-aged, good-humoured soul had evidently been waiting anxiously for my arrival in order to hand over the Camp to my charge as per instructions but willingly stayed on as my 2nd-in-command on being promised a lift to Dimapur in any Army vehicle, whenever she wanted to leave,

A small basha hut was waiting for me and the sight of the empty hut with just one bamboo bunk, was sheer bliss. I dumped my ruck sack on the bunk and emptied it of all soiled damp clothes which needed a wash – 2 pairs of khaki shorts and 2 shirts, some stockings and hankies. The Agent, who expected to return to Manipur within 10 days or so had left one of his shorts with me for dhobying and this too I hung up to dry during the night and suitable attention the next morning. After a sparse Manipuri meal of rice and fish curry I took a round of the Camp, full to overflowing with the evening’s arrivals from Palel, spent an hour or so with the 2nd-i-c, over innumerable cups of green tea and a few pipe-bowls of tobacco.

I remember it as perhaps the most relaxed evening I had spent since leaving Rangoon almost three months back. A grandmother, she relished talking about her husband and grown-up children and especially about the three grandchildren – all safe in Calcutta. A Nurse by profession, she had been posted to the General Hospital in Dimapur as Matron and then volunteered to take up charge of the Refugee Camp in Imphal when the need arose. Though capable and pragmatic, she seemed to have done an excellent job till then but the pressure was beginning to tell – the misery, shortages and a stream of tragic happenings in the Camp had begun to sap her morale and I soon realised that making her continue at the Camp could well lead to a breakdown which would be totally uncalled for. I refrained from saying anything then, but made up my mind to send her away in a couple of days and so free her from the continuing trauma and sleeplessness which had become a part of her daily life.

For me, the day following presaged my entry into an absolutely carefree world where apart from my responsibilities I had no fear of physical damage either by the locals or the Japanese:

I was under the illusion that the Japanese Air Force would not dare make an assault on Indian territory in the face of British Ack-ack and fighter defences which was reputed to be quite formidable. I had obviously not learnt my lesson in Burma. I slept soundly that night and was up early as was my wont. The ‘Matron’ had got a pot of Tea ready to start the day with and, in the event, I was to be grateful for it. The dhoby-woman turned up as we were having our tea to warn me that she would be coming round at 9 a.m. to collect the clothes and it was decided that I would leave them on the bunk in case I went out, as I intended.

It was a bright sunny morning with just a trace of fleecy clouds overhead and I was, quite literally, in a holiday mood. The Matron was anxious for me to go through a sheaf of papers which had arrived a few days back but these had lost all meaning for me at that stage. I told her there would be time for that later in the day but my top priority at that moment was to replenish my stock of pipe tobacco which had run down to critical limits, the last 2 oz. in fact.

After a wash and shave, I strolled over to what is even now known as the ‘Women’s Bazar’ – 3 or 4 long tin-roofed sheds under which stalls selling fish, vegetable, fruit, grocery articles (Milkmaid brand Tinned Milk, etc.), cigarettes, cigars and tobacco and so on, all run by women were ‘laid out in long rows’. I was able to pick up ¾ lb. of Capstan Tobacco in 2 oz. tins @ Rs. 1/- per tin. It was all she had and I was satisfied that it would se me through to Calcutta – all going well. I picked up a few other items like shaving soap, tooth brush and soap and decided to have something in the way of breakfast.

The time was about 0930 hrs. Had just ordered a cup of milk-tea and bread when I heard the first siren go off and shouting to all around me to run or take cover I dashed off towards the Camp which was just a couple of hundred yards away, with my basha almost touching the Town entrance. I kept shouting at the top of my voice for people to take cover and dashed into my basha to fling my small parcel of things on to the bunk and dashed out again to see what was happening. It must have taken almost 5 minutes since I left the bazaar and by this time the deep heart-stopping drone of the Japanese formation with the peculiar beat of the Zeros distinctly audible, was getting louder and louder and in a minute or so I could clearly see the line of black dots, in perfect formation, heading straight for the Camp.

The time was about 0945 hrs and the evacuees who had arrived the previous evening (mostly men) and the women and children who had arrived about 0730 hrs by the first convoy that morning were all busy making family niches with the odds and ends which they carried with them. They were in the open and no trenches had been dug, for the simple reason that no one had dreamed of a Japanese attack so early. The general view among the military was that they would only do so after consolidating their position in the south. In any case it was considered that the administrative and organisational complexities involved in such an attack would be beyond their immediate capabilities.

Unfortunately, the Japanese themselves did not seem to be aware of all this and succeeded in mounting one of the most devastating air raids I had experienced till then. It turned out that there was no immediate fighter opposition and the ack ack batteries seemed to have been taken by surprise. Having shouted myself hoarse to get everybody to lie down on their bellies, I flung myself down 10 feet from the basha door and just managed to beat the first blast from the exploding bombs the closest of which was hardly 100 yards away. The whine of the shrapnel 2 or 3 feet above ground level was somewhat uncomfortable but before I could rise and make a dash for a different spot, I found myself pressed down by a considerable weight of earth from which I frantically tried to extricate myself before the aircraft could come round for the next run.

A quick glance round showed the entire area under a cloud of smoke with several trees up-rooted and a few of the bashas on fire. There were screams and shouts and a loud babble of voices which made no sense whatsoever. I did eventually manage to extricate myself from the large mound on top of me and spurted almost 50 yards before I sensed the approaching roar of the bombers for the 2nd run. Flinging myself down, I suddenly saw a group of 3 young Anglo-Indian boys, all in their ‘teens’ running towards me and shouted to them to lie down. As they reached me the next lot of bombs had already exploded – two of them close enough for me to make my peace with my Maker; 8 bombs had hit the Camp and Field Hospital next to it in a shattering crescendo of noise and the acrid smoke, flying splinters and shrapnel and the screams of men, women and children between the explosions was an unnerving experience. I had however other matters of more urgent concern to bother myself with at the moment.

As I was lying on my face, my forehead resting on my arms, frightened of another explosion, I dared not lift my head but tried to take a quick look from the corner of my eyes at the scene around me. Even in that limited field of vision I could make out the extent of devastation and death; bodies and limbs scattered close to me with the smell of blood mixed with that of cordite impossible to keep from penetrating my nostrils. I had become aware of a heavy parcel of earth flung out by the explosion. I must have lain there for a few minutes making sure the bombers were not making a third run and then tried to bend my knees without success. There was no pain but I felt as if the legs from hip downwards were totally immobile and broke into a cold sweat trying to bend my knees without success.

I remember clearly that I decided to make no further effort immediately until the inevitable pain took charge. I forced myself to calm down and think rationally. It was clear that I had full control of my body and limbs above the waist region and was thinking clearly enough. I also remember telling myself quite calmly that this would be a stupid way to go after having come all this way. It was then that I suddenly decided to make another all out effort to get up and this time it came to me that I was able to move my back without pain though the weight holding me down was somewhat oppressive. I raised myself on my elbows and turned my neck to see what was holding my down and saw a pair of stout legs protruding from a body lying across my back. Making a desperate effort. I managed to roll off what remained of a human body (torso severed at chest level) and stand up.

The scene around me was unbelievable for its starkness. Literally hundreds of bodies, some mutilated beyond any possibility of recognition – men, women and children with their pitiful belongings salvaged from homes in far off Burmese towns and villages scattered all over the Camp area. The Field Hospital with its prominent Red Cross flag on the ground to warn enemy aircraft lay there as a silent witness to this horrendous violation of the Geneva Convention to which Japan was a signatory. Those who had escaped injury, dazed and sobbing were moving about searching for family and precious belongings.

As I stood up and tried to take stock of the situation, my eyes fell on a heap of two bodies – the remains of two lads who had formed a threesome with the young man whose lower half had weighed me down. I found the upper ‘half’ lying close by. None of the three carried any identification having evidently left their belongings in an excess of euphoria with their companions on setting out on what was to prove the last stroll. It took hardly a minute for all this to register and being badly in need of something to steady my nerves, I ran to my basha, a hundred yards away, to collect my pipe and tobacco only to find that it too had had received due attention from the Japanese. Shrapnel had cut through the bamboo walls and missing my clothes had taken out their venom on the Agent’s pair of shorts which needed washing. The tattered remnant was eventually handed over to him as a souvenir of that tragic morning.

A very moving account ….I have only read memoirs by the British before this. I have enjoyed reading all your books also, which have helped me understand something about the period of colonisation in the far East, in which my mothers family had a small part. It also gives a context for the Burma Campaigns in which my father fought . The sheer numbers of people escaping and murdered is shocking and nowadays we can easily forget how many civilians were affected in that part of the world. I did not know that the refugee routes were divided along racial lines…I suspect this was not so true as the year went on and the levels of disorganisation increased.