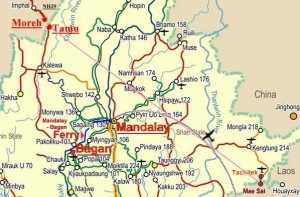

It took me 10 days to reach Tamu, the last camp on the Burmese side of the Indo-Burma border. It was a huge sprawling affair with ‘basha’ accommodation for around 30,000

all sited under thick forest cover which provided some security from Japanese reconnaissance planes operating in that area. Since I was to be in charge of the Camp till its final evacuation, I got my tent pitched on the Burmese side of the small bridge across the Tamu river constituting the boundary between Burma and Manipur (India).

I was soon settled in, had a quick wash in the river and set out on an inspection of the Camp and the store-houses stocked up with thousands of bags of rice and salt which seemed adequate in terms of the numbers expected to pass through and the time limit fixed for final vacation of the camp, – 3 weeks on the outside. The Camp was already half full and, of course, a sizeable number was expected later that evening. As I was completing my rounds I noticed a neatly marked off plot of about 5 acres with somewhat better built bashas each to accommodate ten individuals. On enquiry I was told that the enclave was meant for non-Natives – Anglo Indians or Native sahibs as the case may be – and I knew instinctively that this was going to cause trouble. It was blatant discrimination and under the circumstances totally uncalled for.

It also meant that some form of certification would be required. This camp had been set up by the Govt. of Burma and I had no authority to change the rules under which it was function. My mandate was to take charge of the Camp and run it according to the rules laid down. It must be said, however, that apart from this somewhat mindless attempt at apartheid, I had been given an absolutely free hand in the running of the Camp so I had little cause to complain. Even in the case of the ‘white’ camp, the discretionary power in each case had to rest with me. Equity and rationality were all that was required.

In the event it all worked out well enough and my somewhat liberal interpretation of the term non-Native caused no serious ripples. The Camp staff consisted of a Burmese overseer in charge of 20 Burmese labourers – lazy, good-humoured but reasonably helpful. That night I got hold of the overseer and set down a drill for distribution of rations to the inmates starting at 0600 hrs. the next morning. There were also 10 surface wells dug within the Camp area for supply of water. My major concern was to ensure the highest standard of public health within the Camp in order to avoid the slightest chance of an epidemic. I immediately set apart four basha huts on the outer ring of the Camp for use as ‘isolation’ wards.

I had two men posted at the entrance to the Camp to sort out the ill and infirm and direct them to the isolation ward. I was expecting a doctor with some basic medicines and equipment within a day or two and had decided to hold all the sick in the Camp till they could be checked over by the doctor. We had a large stock of spades and shovels in our stores and I decided that each hutment was to provide 2 male volunteers for the various jobs required to be done around the Camp, starting with digging of latrine, trenches well away from the Camp perimeter. Others were put to the task of putting up lean-to communal kitchens for protection from the sudden drizzles common in the area.

The doctor and his assistant (both Anglo- Burmese) arrived in due course and immediately set to work doing a splendid job covering medical, public health and sanitation requirements of the Camp. It was imperative that the Camp was kept free of flies and after a couple of warnings which went unheeded, I decided to impose punitive fines against any hutment which failed to observe the rules. The fines took the shape of extra labour coupled with reduction in rations which did the trick. Full rations were important since all inmates were anxious to lay aside a certain proportion for the onward journey to Imphal and beyond. The normal duration of stay was about 2 – 3 days though I allowed longer stays provided there was no pressure from fresh arrivals.

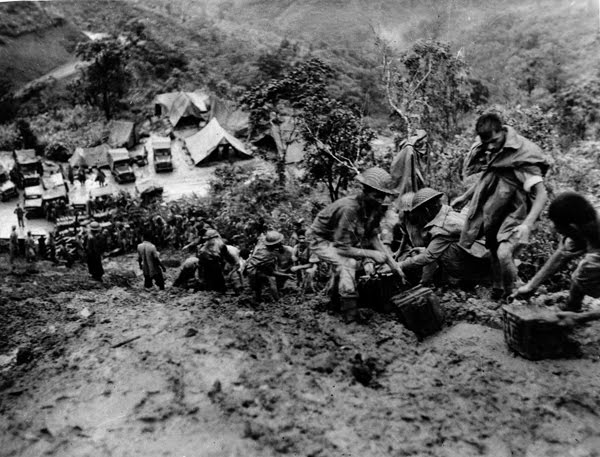

There was no question of the Camp settling down because of the continuous inflow and outflow of refugees throughout daylight hours which necessitated a continuous vigil by the staff and it was seldom that I was able to turn in earlier than 1 a.m. The unaccustomed hardships of the last couple of months coupled to the trauma, in many cases of having to leave behind kith and kin or close friends to die along the road had stretched nerves to breaking point resulting in severe emotional reactions to petty inconveniences on arrival at the Camp erupting into fights and quarrels which had to be dealt with as best as one could.

In the majority of cases, however, the morning sun dispelled the night’s grouses and ill-humour and I never tired of being delighted by the restoration of bon-homie between the families involved in the night’s battle. More often than not, it was I who was at the receiving end of the anger and frustration of both the settled as well as fresh arrivals at the Camp but those were days when I had no inhibitions about giving as good as I got and neither did I have any problems about laying down the law with all the authority at my command. There were no ill-feelings at the end of the day and I was continually amazed at the goodwill and co-operation extended to me by these people. The Camp was almost always full and 20,000 persons in a defined area could acquire an oppressive ambience. There had to be all sorts including some rather attractive young females whose recent experiences had given them a certain air of confidence and devil-may-care outlook. I enjoyed meeting them all, have a mug of green tea or even join them at a meal if I happened to be at the right place at the right time.

There was one ‘zerbadi’ [Indo-Burmese Muslim] family consisting of mother, father and four daughters ranging in age from 18 to 28 – all fairly attractive and with no illusions about the matter either. It was a joy to visit them first thing in the morning and join them for the morning’s cup of Burmese tea. It was the 3rd morning when the Father (in his late forties) dropped his bombshell in what I took to be a humorous vein, at first. He called all the four girls to join us at Tea and then asked me bluntly if I was married.

I laughed and retorted jokingly that I was not simply because I had not yet found anyone who would say ‘yes’. At that the father turned to the four with a question in his eyes and to my embarrassed amazement, all four nodded their heads without a blush.

From the expression on their faces as well as the father’s, I began to realise that the joke had got out of hand, but kept quiet. The father then asked me without batting an eye-lid what I thought of his daughters and I struggled to string together a bantering reply keeping it at a totally impersonal level, something to the effect that with their good-looks, I would have been proud to have them for my sisters. At this he said since sister-ship was out of the question what about acquiring them for wife – all four of them!

I must have looked a comic sight struggling to make sense of what was going on, but he repeated the question quite seriously and the girls kept silent and I decided that the humour had gone out of the situation – if ever there was any. I made no bones about telling them that apart from the fact that I had no intention of marrying anybody at that stage, neither the situation nor the circumstances justified his disposing of his daughters, all educated, in this somewhat casual fashion and that I had hardly expected such an attitude from him. The girls remained non-committal and I decided on the spot that I must show special favour to the family by arranging a bullock-cart for their onward journey, at their expense, at the earliest, which happened to be the very next morning, we said a cheerful farewell and promises to meet in Imphal or Dimapur in a few weeks from then but that was the last I saw of them. I am certain that the girls must have breathed a sigh of relief at the end of a drama which had slipped from comedy into farce.

The Anglo- Indian enclave with accommodation for some 200 persons was also beginning to fill up. My interpretation of the rules did away with the ethnic factor altogether and focussed on more practical aspects like background, profession, income levels etc., and this seemed to work out well with no complaints. I did insist, however, that anyone wanting accommodation in the A-I camp had to see me personally for the chit.

There were good reasons for this. After the first two days when I had relied on the attendants to bring the chits duly filled in by the head of the family, I discovered to my embarrassment that the attendants had been charging the refugees amounts varying between 5/= and 10/= (depending on no. of members) for getting my approval and I only learnt about this practice when one of the new arrivals asked me on what basis these charges were fixed. On my denying that there was any such charge, the whole story came out. I lined up the attendants, read the Riot Act, and ordered total repayment or face immediate dismissal. There were no defaulters.

The Chit rule, however, was responsible for bringing about one of the most moving moments of that great saga. One afternoon as I sat in my tent, facing the entrance completing some paper work, I was suddenly aware of a large dark-clothed figure almost filling the entrance trying to peer inside. Since I sat well back from the flap he was not able to see my face clearly and after a few moments, I saw him step back, stand to attention and in polished but trembling accents say “Good afternoon Sir, can I speak to you for a moment?” There was no mistaking either the voice of the accent and I called his name in some excitement, “EARNEST – for God’s sake come in….” and then the most poignant thing happened. He went down on his knees and broke down – it was a harrowing sight and it took me a few moments to control my own voice. I just went up to him, raised him to his feet and shook him by the hand.

There were others waiting outside and too much emotion would be out of place. He was still clutching the Chit in his hand for my signature. I signed it, but asked him quietly to wait outside till I had done with the others. I had made up my mind. He would share my tent and I would see him on his way in a couple of days.

This was Earnest Joseph, one of my closest friends since child-hood and son of Mr. A.V. Joseph the richest Timber merchant in Burma till he went bankrupt in the late 20’s. Earnest had studied at Harrow but had to leave after the father’s bankruptcy. A highly talented artist who was responsible many years later for the Book of Fame of the Constituent Assembly; the margin on each page illuminated with subjects typical of the State concerned.

Earnest, on arrival at the Camp had been given a highly coloured impression of my ‘inhuman’ qualities and had promptly decided to take necessary precautions by changing into the only spare clothing he carried in his bundle. A warm, dark suit (mercifully minus a tie) and black shoes without socks. He had left Rangoon shortly after I had, made his way to Mandalay by whatever means available and then gone off to Kalaw in the Shan States to spend a few days with some friends. That was typical Earnest. Never having been obliged to earn a living he retained his easy-going, somewhat self-indulgent habits til the very end. His death remains a mystery but the ‘buzz’ has it that he died in a remote village in Tamil Nadu refusing to sell his paintings/drawings which, according to him, would have been a prostitution. There was considerable demand for his work – sacred, not-so-sacred and downright ribald and he could have made a good living out of them but he remained his own exasperating self until the end – but that was Earnest!

He stayed in Tamu for 2 days and on the third I managed to put him on an Army 3-tonner to be dropped at Palel some 30 miles distance. He eventually made his way back to India, none the worse for wear.