February 1942

Mandalay was already chock-a-block with refugees who had turned the city into a public health time bomb. Cholera had started taking hold and our total indent for anti-cholera vaccine on the Government of India reached 20 lakh injections for the Mandalay area alone. The news from the south was increasingly disturbing and after sending off a telegram to the Agent, I decided to make my way down south by river get off at Minbu-Magwe and then, if necessary pick up a bicycle and try to reach Rangoon by road (some 200 miles further south). We were now into the 3rd week of February and the weather still mild in the Burmese context.

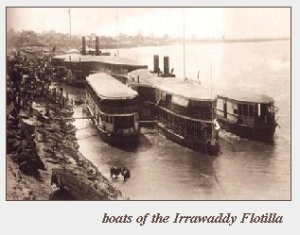

I managed to get aboard a paddle-steamer belonging to the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. Ltd. on its way south and we reached Minbu 2 days later.

Minbu and Magwe are twin cities on the left and right banks of the Irrawaddy river respectively. I was aware that the Kyaw Htoons, very close friends of the family, had a country house in Magwe and that there could be a remote possibility that Mother may have teamed up with them in the event of a general evacuation from Rangoon. It was worth taking a chance before rushing off to Rangoon and getting caught in turmoil there. I got off at Minbu and looked up an old Moplah business friend to get the latest news. He told me that Rangoon had fallen and the city was in a state of chaos. He advised me that even thinking of Rangoon it that state would be sheer madness. I asked him to get me a cycle on purchase and that I would settle with him on my return to Magwe which I decided to travel to in the same steamer waiting to cross over.

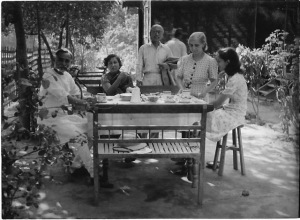

Getting off at Magwe I dashed off to the Kyaw Htoons who had a large bungalow overlooking the river and there, to my disbelieving astonishment I found Mother with the rest of the Htoon family enjoying a cup of tea!

Mr. Kyaw Htoon was a Karen lawyer happily married to an Englishwoman.; 2 children – Olga and Vernon – all of us in the same age group. It was quite tumultuous meeting and as soon as the excitement died down I was given an overall round-up of events so far.

As Rangoon was ordered to be abandoned, father joined the Army convoys with one of his own comprising of some 30 odd lorries carrying rice-milling equipment in full working order and another 50 loaded with un-husked paddy. Before moving off, however, father arranged for 2 lorries to be placed at Mother’s disposal; these carried spares for the rice mills but there was sufficient room for 5 individuals with baggage in each and this turned out to be a boon.

Mother, knowing that the Kyaw Htoons were in Magwe, decided to stop at Minbu and crossed over to persuade them to join her on the journey to Mandalay and, in fact, stick together for the rest of the stay in Burma.

The Kyaw Htoons were undecided but I told them categorically that they had no option. There would be nothing for him to do and that there was every possibility of the law and order situation breaking down and creating an ugly situation. I also told him that I had everything arranged in Mandalay in the way of shelter and once there, a decision would have to be taken regarding further movement towards India.

Fortunately, both Olga and Vernon Htoon were enthusiastic about the plan. She had fortunately passed her BA exams early in 1941 and he (Vernon) had managed to secure a Commission in the Burma Rifles whose Training Centre was in Mandalay.

The little Austin with the driver Yakub formed part of Mother’s little convoy and it was decided that Mother and the elder Kyaw Htoons would travel in the Austin and the younger three in the lorries.

The Kyaw Htoons took this decision, which could well mean a long and uncertain separation from their homeland, with typical stoicism and were packed and ready for the road within an hour’s time. The house too had to be locked up and secured, more for psychological satisfaction than conviction regarding safety. We crossed over to Minbu by steamer and mounted our respective vehicles with our baggage which consisted of a suitcase each. My moplah friend was asked to return the bicycle with thanks and we were on the move.

We stopped the night at Toungoo had a good night’s rest and reached Sagaing, my temporary home, late the following evening. The cottage received general approval and we settled in without much ado. Vernon decided to leave for his regiment the very next morning and that was the last I saw of him. A wonderful friend, he rose to command a battalion and kept in touch well into the 60’s after which there has been total silence.

The Agent reached Mandalay the next morning and after a brief session concerning our programme of work and main priorities in terms of setting up Refugee Camps along the Mandalay-Tamu route and their provisioning for the hordes of evacuees expected along that route. This, of course, had to be the sole responsibility of the Government of Burma but I was directed to associate myself closely with every aspect of the work in order to be in a position to take over at short notice. This was significant since it was an indication that the Government of India was increasingly taking over responsibility (financial and administrative) for all aspects of the massive Evacuation infra-structure that was being built up in order to cope with the problem at every stage.

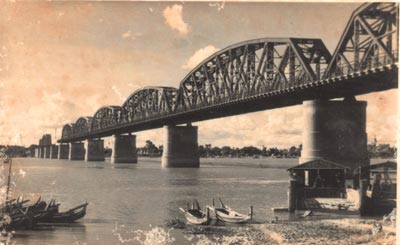

Our discussion made it clear that the major factor responsible for unnecessary misunderstandings, delays and friction was the lack of understanding and agreement between the Burmese government officials and ourselves in regard to specific areas of responsibility, administrative and financial as also powers to issue passes for crossing the Sagaing bridge on certification of completion of health formalities.

The Agent decided to call on the Governor at the summer capital Maymyo, immediately in order to finalize a host of issues and problems pending decision for sometime. On his return that evening, I was in for a rude shock. Quite simply, I was to represent the Agent/Government of India in all matters involving law and order problems, Camp management, health clearances and issue of passes and daily review of infra-structure development along the evacuation route.

The Agent had decided to keep the bombshell for the last. As I was getting up to leave he casually asked me to stay on, lit a cigarette asked me to light my pipe and then let fly. I was told without any preamble that a regular Air Evacuation Scheme was to commence in 2 days time and that I was to take charge of it! I almost collapsed in my chair since we had discussed the problems involved in operating such a scheme earlier on and had agreed that, at best, it would be the most thankless job on the Evacuation platter. Of the more critical aspects, obviously the selection of passengers on each flight would be the most troublesome. Of the thousands who would lay claim to a seat from the 40 available each day –

the Dakotas were considered new at the time – selection would have to be on the basis of criteria to be strictly applied in each case.

We kept them simple and straightforward: Women, 40 years and above; ill or ailing handicapped children below 16 years; those prepared to pay the 120/= per seat fixed by the Government of India up to Calcutta. Men above 50 years with otherwise similar qualifications. The bottom-line was that I had absolute power to make exceptions as considered appropriate. I used these powers to help a number of deserving individuals – old disabled and sick, as will be seen later.