[December 25- 26, 1941

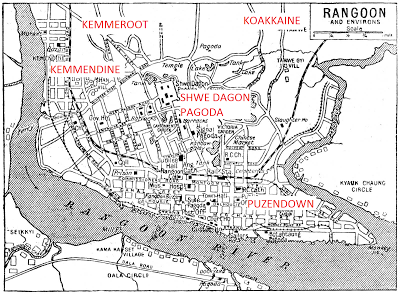

Rangoon]

By the time I started back for home it was late afternoon and what I saw started raising butterflies in my stomach. I stepped on the pedals of my Sunbeam racer and as I reached the house – a typical wooden 2-storeyed dwelling within its own grounds – my heart took a violent somersault. Half the roof was gone and there were clear signs that the morning’s work had left it in bad shape.

We lived on the first floor and miraculously the wooden stairway was intact. I knew Mother would be there since she was on night-shift as Ambulance Driver at the Red Cross Casualty Station, and bounded up shouting for her. She’d had a harrowing experience with a miracle thrown in for good measure.

Jehangir our old and faithful retainer also appeared and gave me a brief account of what had actually transpired. At the time the planes came over she was at the dining table writing letters.

Jehangir came rushing up and literally carried her off downstairs to a small air-raid trench we had dug in the garden with an old derelict ‘sampan’ for a splinter-proof roof! Soon the whole area came under attack and two A.P. bombs hit the house. One took away part of the roof and the second went straight down through the dining table and wooden floor and buried itself in the ground floor without exploding.

Apart from the gaping holes the house still stood four-square with the furniture etc. intact. However, we were advised to move out with whatever we could carry away in the small Austin 10 which, with its young driver Yakub sat unscratched in the garage. With that unexploded bomb comfortably ensconced in the ground floor haste was called for and we took remarkably little time in getting way from that beautiful little house and dumping ourselves on the premises of the Ladies Monday Afternoon Club on the Royal Lake, of which mother was President at the time.

At this time the family consisted of just the three of us – Father, Mother and myself; Ahsan had shifted to Calcutta as secretary to Mr. G.L. Mehta of Scindia Steamship Co. There has been no mention of Father till now. Though we knew his appointments for the day, it was obvious that after the bombing the priorities would have changed. As the Japanese push into Burma developed the realisation grew that a general withdrawal of the British Indian forces together with the Administrative set-up had to be considered a distinct possibility and it also dawned on the authorities that a massive withdrawal on the scale envisaged would also require an efficient commissariat organisation headed by someone who not only knew where the resources could be found but had the necessary stature, respect and leadership to be able to commandeer these resources on an equitable basis.

In Burma the basic item had to be Rice and it has to be said that there was no one who had a deeper knowledge of the various facets of the Rice Trade in Burma from Cultivation to Labour, Marketing, Export etc. etc. as also the identity of the major Companies and individuals involved in various aspects of the trade. His various Papers and Notes on the rice industry of Burma had been acknowledged as constituting Basic Reference Material for Govt. Policy formulations. With these credentials his appointment as Director of Civil Supplies to be quickly extended to cover Army supplies as well was inevitable and I think he was the first and perhaps the last Congressman to be given the rank of Honorary Lieut. Colonel in the British Indian Army. He was a difficult man to keep pace with but one had no option; it became a matter of family prestige. On the 25th we managed to track him down at one of his Emergency Meetings to meet the growing state of unrest in the country and he was told that his next meal would be available at the Monday Afternoon Club, as also hopefully, a Bed.

The Club was beautifully sited in a large compound below the Lake Bund. That night Rangoon was in mourning and a great deal of time was spent trying to locate friends who had been forced out of their homes due to bomb damage.

Some had lost close members of the family; we mourned for them but there were no tears. Mother’s main concern then was the safety and welfare of her students studying in Zeenat Islam Girls High School started by her some ten years back. The School building was safe and in course of time it also turned out that none of her 1000 odd students suffered any hurt or damage either then or in later attacks. So far so good. Father returned home about 11 p.m. and Jehangir in his usual unobtrusive fashion managed to serve up an excellent hot meal after which things began to acquire a less sombre hue.

It was just after midnight and the three of us were going over the previous day’s events and discussing our respective schedules for the day – 26th Dec. 1941 – when we noticed the headlamps of a car turning into the drive. It belonged to Mr. Robert Hutchings, ICS, Agent to the Government of India in Burma and the driver carried an envelope for me; and from that moment my life took a completely new direction.

From Trade & commerce I was to take a leap into the service of the Government of India in the Ministry of Commonwealth Affairs to be followed by the Ministry of Steel Production (6 months) the Indian Navy till 1963 and finally IOC Ltd. till final retirement in 1971. However all this was well beyond the horizon at that moment in time. My main concern was what the letter had to say. It was official, on the Agent’s letterhead intimating, in stark terms, my appointment with immediate effect as Assistant to the Agent of the Government of India in Burma on the same salary as I had been drawing from TOMCO which considering Govt. salaries at the time, was most satisfactory. It also informed me that the management of Tata Oil Mills Co. Ltd., had agreed to my ‘transfer’ to the Government of India till as long as required.

I had greatly enjoyed my 7 years with TOMCO and the Company had been very good to me.In any case, with our Godown having received a direct hit and the Japanese almost at the front door it was obvious to me that I would either have to return to India, losing my independent status or resign a dilemma from which I was neatly saved by the letter in question.

Whilst all this may read well on paper, I must make it clear in all honesty that I had been aware for some time, ever since the Japanese moved in Singapore, that the Agent’s fertile brain had been busy (in its spare moments) on devising a scheme for high jacking my services. I discovered later that he had already written to Mr. Bozman, ICS, Secretary, Commonwealth Affairs in this connection obtaining his approval in principle, to the scheme.

With my temperament and zest for the unusual and exciting, I did not waste too many minutes in confirming my delight in accepting the appointment and informing my new Boss that I would present myself at the Office at 0800 hrs sharp, which I did. I had not the foggiest notion then as to where it would lead me but the road was open and the horizon beckoned. At 29, you don’t ask for much more! My parents had no hesitation in approving my decision and – on the other hand, I greatly liked and admired Mr. Hutchings – sentiments which were to be considerably strengthened in the months ahead.

At 0800 hours on Boxing Day 26th December 1941, on the dot, I presented myself at the Agent’s Office, housed in a part of his largish residence in Windermere Park. The Agent and Mrs. Hutchings had just finished breakfast and were on their second cup of coffee when I was asked to join them and that set the pattern for the next 5 to 6 months whenever I happened to be at ‘Headquarters’ e.g. wherever the Agent had his office at the time.

Working with Mr Hutchings was a major influence in my life. He laid no claims to being an intellectual but his sheer dynamism and air of confident authority made me proud of being a part of his team. He was junior to many of the ICS officers serving in the Govt. of Burma but he represented the Government of India, and that was enough. He let no one forget that it happened to be the brightest Jewel in the British Imperial Crown! Tall, gaunt of face with an oversized aquiline nose, he could turn into a raging behemoth when the occasion demanded and mostly against his own countrymen but had the grace to laugh at himself in an embarrassed sort of way. However his ability to laugh at his own foibles seldom left behind any perceptible ill feeling or bitterness on the part of his opponents.

He had the rare gift of being able to get to the core of the problem and then unravelling it methodically in order to be able to work out the various options available for its solution. I would be in office at the stroke of 8 a.m. and we would go over the day’s programme over a cup of coffee which Mrs Hutchings would pour out as soon as she heard the tinkle of my bicycle bell. Those were busy days and I had no reason to miss not getting my evening games since I got all the exercise I needed from cycling around the city. Often enough there was additional excitement trying to keep out of the way of Japanese Zeroes belting down low over the highway in pursuit of Heavy Vehicle Convoys, military and civil, on the Windermere Park Road which happened to be a byepass for the road to Mandalay. I can remember one hairraising occasion when under a somewhat egoistic notion that the Japanese Air Force had designated me personally as their main obstacle to the conquest of Burma, I flung myself off my bicycle and dived headlong into the roadside monsoon ditch. It was a matter of minutes and on finally reaching office I discovered that the Agent was out. Poor Mrs. Hutchings was quit aghast at my appearance and promptly produced a pair of shorts and a shirt belonging to Mr Hutchings which by their enormous size turned me into a scarecrow providing much amusement all round. He was 6 feet plus as against my somewhat more modest 5’!

Another of Mr. Hutchings strong points was his ability and willingness to trust and devolve powers without laying down inhibiting reservations, which in my case created a bond that I greatly cherished. There was never a question of British or Indian. Within a matter of days he made me aware of his confidence and never resorted to spoon-feeding. I knew what was required to be done and why and the rest was my business.

For me January 1942 was a month of intense activity and toil working late into the night preparing myself for the tasks and responsibilities ahead. The Agent had taken me fully into his confidence regarding our future status in the developing situation and in particular, what he foresaw as being my responsibilities vis-à-vis the Refugees and the whole process of Evacuation particularly from Mandalay northward to Manipur. It is remarkable how correct his assessment turned out to be in the final analysis. January 1942 also witnessed a massive surge of refugees from southern districts into Rangoon and the surrounding areas. The first stream to leave Rangoon took the road to Prome with some hazy notions of moving on from there to Cox’s Bazar on the Arakan Coast thence to TaungUp, Chittagong and finally Calcutta. We had to know more. No one seemed to have a clear picture of what this long march could entail and it fell to the Agent to make the first positive move in this direction. He decided to send me to Prome on a swift recce mission and since I still have a copy of the original Movement Order, I am reproducing it below since it provides and excellent example of his manner of working.

Memo

Movement Order

You will proceed on 31st January 1942 to Prome in Car No. 1999. At Prome you should report to the Deputy Commissioner, or in his absence the District Superintendent of Police, and enquire generally into the number of Indians waiting in Prome district to go up the Prome Taung Up road and as to their condition. You will also report what you find of Indians settled in camps and villages at the Rangoon-Prome road. You shall return to headquarters not later than the afternoon of Monday the 2nd February 1942.

Sd/= R.H. Hutchings

Agent of the Government of

India

- Tyabji, Esq.,

Assistant to the Agent

of the Govt. of India in Burma

Rangoon.

This Memo was received after midnight and I was on the road to Prome at 5 a.m. sharp. Even at that hour I found the road almost choked with Indians fleeing the stricken city in a blind endeavour to put as much distance as possible between themselves and Rangoon. Men, women and children carrying whatever they had managed to salvage on their heads and shoulders. The northward migration had begun as a trickle with the first air-raids on the Capital over a month back and had alerted both the Government of India and the Government of Burma to two major problems (1) the critical need to prevent a general exodus by Indian labour in order to maintain stevedoring services, civil public health, railways and the host of other services which were dominated by Indian labour merely on the ground that Burmese labour was both inefficient and therefore more costly, and (2) the obvious dangers inherent in a mass exodus of this magnitude in terms of outbreak of cholera, degradation of the areas on either side of the roads and above all, providing this mass of humanity with minimum essential facilities such as shelter, rations and drinking water at pre-determined halting sites. Camps were being set up 20 miles apart (that being a day’s march) and were to be stocked with rice and salt only. I stopped at regular intervals to talk to individuals and groups concerning their intentions and resources and to find out if they had any idea of the route to take and why and the difficulties and hardships ahead.

I discovered that the vast majority in that stream were Oriyas from Orissa travelling in well defined groups, village or caste-wise, with cash resources ranging from 50/= to 1000/= rupees per family which was all the money they had been able to lay their hands on at short notice. Many had fled leaving behind substantial sums owing to them by employers/contractors or maistrys. Almost none had any idea of the long and arduous trek ahead of them but then neither did I. according to my reckoning there were just 50,000 Indians on that road that day, 31st January 1942, between Rangoon and Prome, a distance of approx. 120 miles. Reached Prome around mid-day and met both the Commissioner & DSP (both British) with whom I was to establish an excellent working relationship without ado. I got a good idea of established and projected Camps in and around Prome, facilities available in resources and man-power and anticipated shortages and bottlenecks. I was told that finance would not be a problem. As planned, Prome district would be able to handle approx. 50,000 refugees on a 24 hour cycle which meant that the Camps would have to be emptied every 24 hours to accommodate fresh arrivals. This in turn meant that the facilities along the Prome-Taung Up road, including adequate provision of boats for crossing the Irrawaddy at Prome or other selected sites would have to be suitably strengthened in order to avoid ‘piling’ up of refugees at these points resulting in the creation of a host of problems like hygiene and law and order which in the overall would cause friction between local Burmese and refugees resulting in dis-order and chaos. Apart from all this was the harassment of refugees by the Burma police and petty officials which even at that early stage had assumed critical proportion and was strongly brought to my attention by Indian settlers, traders and shop-keepers in the area, many of whom were known to me from my earlier visits as TOMCO representative.

I lodged a complaint with the Commissioner and brought it to the Agent’s notice in my report on return to Rangoon. My major concern at that stage was the realisation that neither the Burmese administration nor anyone else seemed to have any clear idea of the physical difficulties likely to be encountered by the refugees along the Prome Taung Up route which in a general way ran along the foothills of the Arakan Yomas. There was no positive information even in respect of availability of water and suitable camp sites for such large numbers along the route. The attitude of the tribal population along the Prome Taung Up route was another worrying factor about which nothing was known. It was obvious to me that the first few batches were likely to face tremendous problems but my suggestion that we should hold back any movement northwards till such time as a proper recce had been carried was received with no particular enthusiasm from the Commissioner and DSP and even less from the refugees themselves. In fact, it led to a near riot and I withdrew the suggestion for the time being. I regret to have to record that in the event, the first batches of these ill-equipped men, women and children met with total disaster and from information which reached us later it was evident that only a handful had managed to struggle through to Akyab and beyond. The only positive outcome of this ill-fated venture was to give a small boost to my credibility status; my views were taken somewhat more seriously by the agent as well as the Burmese administration and this proved to be of considerable help later on when I moved up to Mandalay for the final phase of Evacuation from Burma.

(to be continued…)

Just glanced through an exciting fragment. of the Burma Story. Had heard something of it from my father Ahsan , — as also from his twin brother Nadir. But not in detail. V. grateful for the opportunity to view and absorb this powerful story .. at my leisure.

(I am the niece of Capt. Nadir Tyabji. When I was born in 1946, he telegraphed my parents suggesting the name “Nadira” for me.- and I have “worn ” it since then.)

Thank you for a wonderful Blog.

Thank you!

Amitav

What a tale! We once had a cook in Bombay who said he had walked from Burma during the war. It must have been a dreadfully difficult and demanding trek.