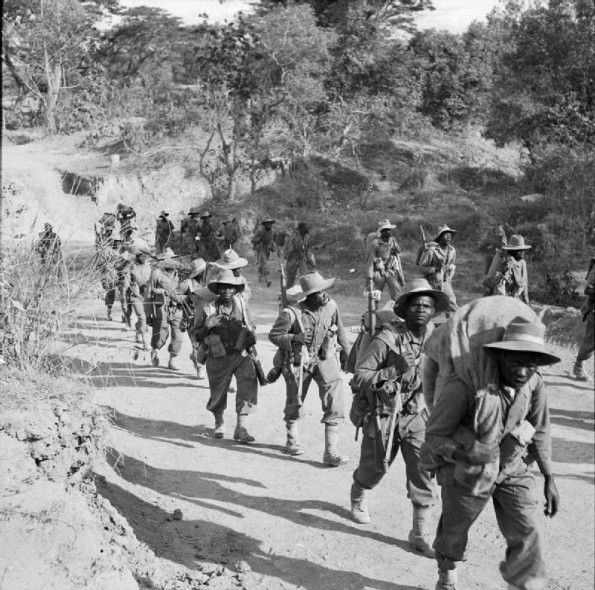

Troops of 11th East African Division on the road to Kalewa, Burma, during the Chindwin River crossing.

Troops of 11th East African Division on the road to Kalewa, Burma, during the Chindwin River crossing.

By this time the DC had become a good friend and we enjoyed working together; I gauged the needs and he did his best to meet them. Two or three days after the bombing, as I was going round the City Camp one morning on my usual rounds, I was suddenly confronted by a tall, lean man with greying hair, dressed in pyjama and kurta and before I could call out his name found myself lifted off the ground in a tight hug. With tears streaming down his bearded face he kept repeating ‘Nadir baba’ and refused to let go of me.

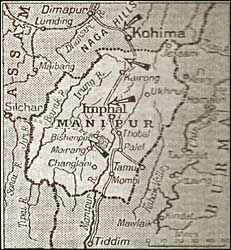

I knew immediately that there was something wrong; his body felt burning hot and he was covered in sweat. I touched his brow and hands and asked him what was wrong. I went cold when he told me of his problems; these were the obvious symptoms of the dreaded cholera and no time was to be lost. I had him admitted into the Field Hospital without delay. They took him in hand immediately, but the duty M.O. told me quite frankly that in his opinion matters had gone too far for him to be hopeful but – he would do his best. I sat by the faithful retainer’s side for almost an hour listening to his story from the time he left Rangoon. All had gone well till he reached Kalewa but he felt that he must have picked up the bug before reaching Tamu. Since the Camp had been wound up, he carried on towards Palel on foot, but was fortunate in being able to get a lift in an Army convoy up to Imphal, and there he was.

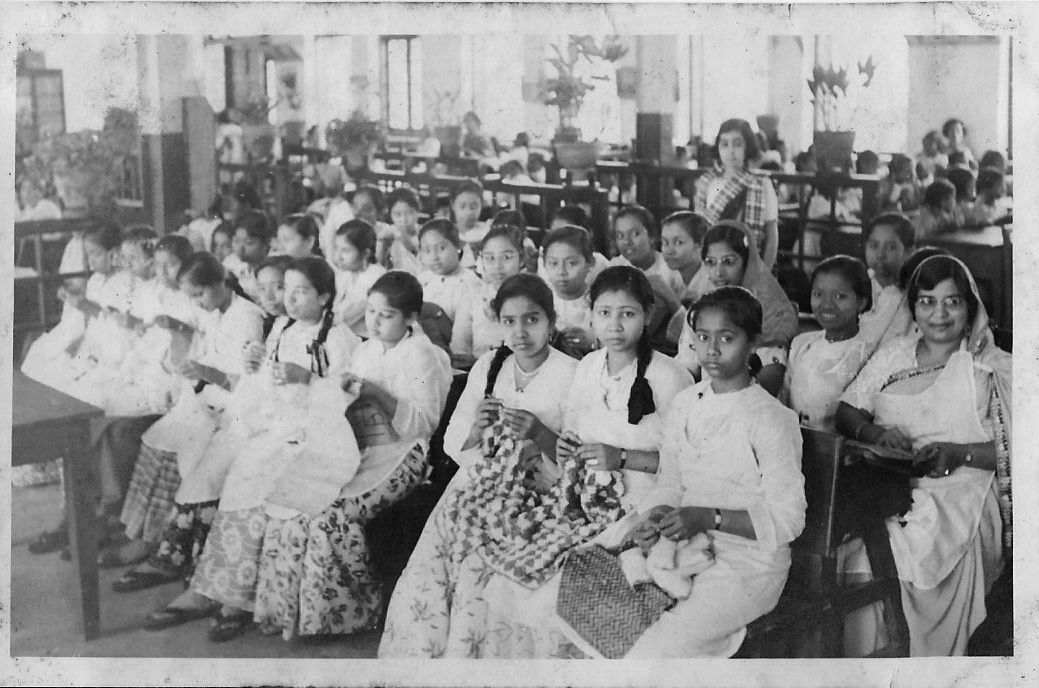

Abdul Rehman had been with us for almost 15 years, first as our house driver and later as Bus-Driver in Zeenat Islam Girls High School started by Mother of which she was the Hon. Headmistress.

It had developed from an initial 40 students (mostly Zerbadis[Indo-Burmese Muslims]) to almost 1,000 students by end 1941. Confirmed reports indicate that the School is still a going concern and flourishing under the dedicated guidance of its Old Girls trained under Mother’s strict supervision. However, poor Abdul Rehman was going down fast and the doctor told me that since there was little chance of recovery, it would not be possible for them to continue to accommodate him in the Hospital with a large number of emergency cases waiting for proper beds. I saw the point and with the DC’s permission shifted him to an out-house in his compound where the poor man met his end in peace. It was early morning, and I was able to see him through those last moments – born in a remote village in U.P., we buried him under a shady tree on the hill-side. I had buried many along the road from Mandalay but this hurt the most. He had not seen his family for almost 5 years and was so looking forward to joining them again with a tidy sum saved up. I took charge of his meagre possessions, requesting the DC arrange their delivery to the family due course. I know he honoured my request. The money I kept with me till I got to Calcutta and then arranged its actual handing over to his wife through the local DC’s office. I received an acknowledgement from the wife in due course and that brought this sad episode to a close.

We were well into June 1942 and the heavy rain (almost 200 inches) was beginning to create problems. Fortunately most of the Camps were empty as also the hospital and we arranged for the last few hundred refugees to be transported to Kohima-Dimapur by the 3rd week of June. At a last informal meeting with the DC and the Army representative (a Major), it was agreed that there was nothing left for me to do in Imphal and that I should leave in a convoy leaving for Dimapur the next morning. Having walked all the way from Mandalay and with no further responsibility on my shoulders from there on, my ego and perhaps the prospect of a leisurely trek through that beautiful country,

60 miles to Kohima and 40 miles from there to Dimapur, made me suggest to my friends somewhat diffidently that I would like to do the journey on foot, if they did not mind.

They did protesting loudly that it would be madness, quite unnecessary and the torrential rains in the area could make it somewhat unsafe. I tried to see the point without much success but in the end agreed to take a lift. Evidently the Gods were on my side.

As luck would have it, I was seated next to the Driver in the last truck, which developed trouble a few miles out of Imphal. The others broke convoy discipline and carried on which gave me no qualms whatsoever for I knew my chance had come. Eventually the truck came to a halt at a small hamlet, the bonnet was lifted and a few minutes later I was informed that there was not a hope of our proceeding further that day owing to a major breakdown. I lost no time in getting free of the Army, said my thanks and farewells as solemnly as I could manage and was on my way without a care. The pipe was pulling well, I had filled up with a couple cups of green tea and life was sheer bliss. Unfortunately I gave no thought whatsoever to the possible consequences of my escapade in so far as the people sitting in Calcutta and Bombay were concerned, waiting anxiously for some news of my whereabouts after leaving Imphal. A DR from Dimapur to Imphal with a message for me was sent back with the information that I had left Imphal in a convoy some 3 days back and should have reached Dimapur the same day or the next latest.

The DC at Dimapur seemed to have scoured the area for my whereabouts and also requested his counterpart in Kohima to do the same.

Since I had hopped off the convoy, they had no means of confirming how, where and why I had disappeared and so, in order to place everything on record, informed the Agent, Mr. Hutchings, that having scoured the countryside without luck, he greatly regretted having to suggest that I be listed ‘presumed missing if not dead’. Poor Mr. Hutchings. I believe he had been telling all and sundry (whenever the topic came up) that he just could not believe that anything would happen to me. In his view I possessed an uncanny instinct for self-preservation and that I would, without a doubt, turn up like the proverbial bad penny when least expected. Needless to say the telegram from Dimapur gave his optimism a bit of a jolt but worst still, what would he say to my Mother anxiously waiting for news from him. In the end he decided to play it straight and repeated the Dimapur telegram verbatim adding a few words to say that he expected everything to come out right in the end and not to worry. I shall come back to this a bit later.

Four days on the road to Kohima, spending nights in small hamlets and repaying their hospitality with the princely sum of one rupee which was invariably accepted with considerable enthusiasm. This included the evening meal and morning Tea! Three days to Dimapur and I was almost home and dry. Unfortunately, my sudden appearance in the DC’s office caused some consternation. The DC, a youngish man could not quite make up his mind whether to receive me like a long lost brother or to display the right temperature of coldness for having forced him to send off that unfortunate telegram.

I quickly sensed his embarrassment and lost no time in reassuring him that he was not to blame. If anything, this unfortunate situation had arisen entirely due to my own irresponsible action. He was not to worry! I would ensure that the Agent got the full story from me which would put the whole thing in the right perspective. This made him feel somewhat better and I was invited to go over to his bungalow and freshen up with a bath. He joined me for Tea later and since my train to Calcutta was not to leave till eight in the evening I thought I would run down to the Hospital where almost 75% of the patients were refugees. He decided to come too, and we strolled over after Tea. Going through the Men’s Wards, I noticed quite a few familiar faces, from Tamu and even earlier. Most of them were skin and bone but the doctor said they were all out of danger and would pick up fast. The mere fact of being a few days away from their homes was a tonic of sorts. We exchanged greetings and shook hands and these were the last tangible memories of our long association on the road from Mandalay to Dimapur.

Then we came to the Women’s Ward and as the Matron met us I told her about the two delivery cases on the road to Tamu. An English girl she listened to the story in a matter of fact sort of way obviously uncertain whether to accept it or let it be. I was a bit amused at her attitude and moved on towards the beds where a majority of the women had babies with them. As we moved up there was a slight commotion on the far side and looking round, I found one of the women waving her hand obviously trying to draw my attention. All I needed was a second look and was over-joyed to find my very first delivery case sitting up in bed with her youngster in her lap and telling everyone around her that I had been responsible for saving her child! Though delighted at this blatantly inflated recognition I thought the matter had to be put right and gave them all a highly coloured re-cap of the affair which brought peals of laughter from the other beds. By this time, my second patient, the mother of the baby girl, neighbour to my first, had also woken up and drawn my attention to the bouncing baby in her lap. I sat down and we had a long chat and it was good to see that the young British DC who spoke good Hindustani had also joined in the spirit of the occasion. However, the time came to say goodbye and as I was about to move on, the mother of the boy shyly asked me to write down my full name and address. She could read English and asked me what the ‘N.S.’ stood for. I wrote my name down in full and she asked me to underline my ‘christian’ name to be able to tell her husband.

In order to wind up this episode, I must record the fact that it was in September 1945 when I was doing a Course at the Staff College, Quetta, that I got a letter from the lady’s husband (a driver in the RIASC) recalling my part in the delivery of his son on the Kalewa-Tamu road and informing me that the family was well and happy by God’s Grace. The letter concluded with the information that they had named their son ‘Nadir’ in remembrance of the somewhat unusual circumstances of his birth. The letter was in Urdu and has been lost – its being written was an act of grace which has remained etched in my memory all these years.

Then it was time to leave and that was when I faced my moment of truth.

In saying goodbye to those women, I was in fact saying good bye to an adventure which had begun with the bombing of Rangoon, taken me to Mandalay and from then on, turned me into a refugee like any other of the twenty odd lakhs who had taken the road to India with its promise of safety, security and a new life. That circumstances had cast certain responsibilities on my shoulders in relation to the others was incidental to my basic status of refugee. There was, of course, one factor which made a difference. I have been a loner all my life and all my travelling whether on foot, bicycle, rail or steamer, on business or pleasure carried in my mind a certain element of adventure and excitement and this is exactly how I viewed my duties as Assistant to the Agent and my trek northwards. Walking was a pleasure and the ruck-sack on my back gave me a wonderful sense of being entirely on my own. My responsibilities added to it a sense of being needed which at 29 years of age is something to cherish. Leaving the Hospital I realised that I had finally come to the last link of my association with this massive operation; perhaps among the world’s biggest of its kind (involving a vast stream of humanity trudging over a distance of approx. 800 miles of rugged country living on rice and salt most of the time and leaving behind countless dead who would be mourned only when the journey ended. I was entering a world which I had almost forgotten. I knew I was in for some shocks and would have to come to terms with emerging realities in the hours and days ahead from total involvement to being just a refugee.

Interested in another perspective to the Exodus, for this blog? I can connect you to the grandson of a Tamil refugee from Burma who has a memoir translated from Tamil which is poignant because the man lost his family in the travails.

Thanks for publishing this absorbing account from a remarkable man. I’ve just read a book about the exodus. My father who was a medic based in old Delhi, had various aunts and uncles who apparently made this journey but I have no idea what happened to them.