Imphal, 1942

Roberts ran a Spartan household with just a bedroom and living/dining room in full commission apart from the Office complex. He had a Camp bed set up for me and I woke up at six feeling fresh and ready for the fray and the thought of another attack remained an unspoken dread and neither of us had to mention it at breakfast. I was fully conscious of the traumas the day held for me. The male component of the large group of women who had been delivered at the Camp the previous morning before the air raid, which had been held back on our instructions some 5 miles down the road due to accommodation problems would be reaching the Camp around 7.30 a.m. in a highly emotional frame of mind since the news of the raid and casualties had spread far and wide in the valley.

We discussed the matter and decided to request the Army maintain a discreet presence in the neighbourhood of the various camps in case matters tended to get out of control. I was at the Camp just after seven o’clock and the first batch of menfolk started trickling in around 7.30 as expected. They presented themselves at the Camp gate silent and ashen-faced, with dread in their eyes as they scanned the emptiness beyond. Only a few sobbing women and children waited at the gate to meet them and they were immediately surrounded by the men imploring them for news with baited breath. Apart from a few, most of the men seemed to have steeled themselves for the worst and wept in silence.

After a while I decided to intervene to inform them that there were a large number of women and children in the Camp too shaken to move out of their enclosures.

I suggested that the men should go round in an orderly fashion to meet their families or confirm their whereabouts. I also told them that we would offer all help to visit the various hospitals in order to contact their missing wives and children as and when they were ready. I had just moved away from the gate and was talking to the Matron when an obviously agitated Anglo-Burmese man (in his late thirties) wearing a loungyi and khaki shirt, carrying a bundle on his shoulders came to me and speaking in English told me in gasping sobs that he knew his wife had been killed in the raid but could I help him to identify the spot or area where she had been seen last.

The query sounded almost grotesquely incongruous but I kept a hold on myself and asked for details concerning her height, complexion etc., hair-style and clothes she had been wearing. His description of her physical characteristics was hardly helpful but it was when he came to describe her clothes that my memory took a sudden jolt. Even as late as 1942 the vast majority of Burmese women stuck to the traditional white ‘aingyi’ or waist length jacket and only a few, even among the younger generation, wore coloured aingyis – mostly pastel shades of yellow pink or blue. Even in that moment of stress I remember clearly his telling me with an element of pride that his wife must have worn a pink aingyi above a dark mauve loungyi since that was all she had with her. It just happened that as I had been returning to my basha from the bazaar after the siren had sounded, I had noticed, quite by chance, a small group of women under a large banyan tree some 150 yards from my basha and whereas the rest were in white aingyis, one of them was wearing pink and it had registered.

I had seen no one else in a coloured jacket that morning. I told him casually that I thought I had seen a pink jacket but since all the bodies had been removed and disposed of it may be impossible to confirm the location where she had been killed. He asked me to point out where I had last seen the pink jacket and I pointed to a large tree which had been split in half by the blast. I picked up a spade and we walked over to the large crater next to the tree. The area had been totally cleared of the previous day’s gruesome debris and as I tried to explain that there was little chance of finding anything buried in the crater since everything had been blown clear, he hardly seemed to take any notice of what I was saying. His eyes were fixed on the crater and he suddenly burst into almost maniacal action digging methodically from the rim downwards to the bottom, to a depth of 18”.

After about 30 minutes, as I was wandering looking absently for other souvenirs of the raid, I heard a loud shout from the crater and ran up to discover that my young friend was tugging at the shoulder-loop of a red Shan-bag which he managed to pull out, place it reverently at his feet and kneel down in the Buddhist ritual of prayer. Eyes closed with tears streaming down his face and body shaking convulsively, I found myself rooted to the spot finding it difficult to accept the reality of this near miracle. It just did not make sense and yet the evidence was right there. Having calmed down, he picked up the bag and spade and scrambled up; holding out the bag, he asked me to look inside. The lips had been closed with 2 safety pins and as I looked inside I discovered 3 or 4 bundles of currency notes lying at the bottom together with other bundles of currency note lying at the bottom together with other bundles of papers and bits of jewellery.

I handed the bag back to him with a reassuring smile and he then quickly emptied the contents on to the ground, checked through and confirmed that his life savings was intact! As we walked back, I learnt that he was an employee of the Burma Railways and being Anglo-Burmese he did not want to stay back in Burma under the Japanese but decided to take a chance in India. He had drawn all his dues from the Railways and Bank savings and handed them over to his wife for safe custody in case something happened to him. In the event it was a tragic reversal of fortunes. The shock-waves from the loss of his wife would hit him by and by but the loneliness would somewhat be tempered by the fact of her having assured his immediate future even as her life was taken from her. He took some water but refused all food that day and left for Kohima the next morning. I can still remember almost every detail of this episode, at times with a lump in my throat, and often wonder how things went for him from the time he left Imphal.

There was a slight silver-lining to the cloud of gloom over the camp in the news that almost 80% of the morning’s arrivals had found members of their families either in Camp or hospital and they were invited to stay on till their dependants were released from hospital. Many of the injured were to be shifted to the Hospital in Dimapur and wherever feasible we tried to ensure that the family remained together.

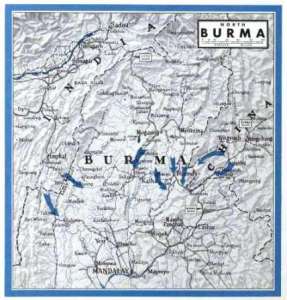

With increased military traffic on the Dimapur-Tamu road,

the Army was prepared to lift a far greater number of refugees on the return trip to Dimapur and hence, we had no difficulty accommodating almost 90% of the refugees in Army trucks on their way to Dimapur. We almost finalised this plan the day after the bombing with a few minor details remaining to be tied up.

Roberts dropped in round about 1230 hrs and I told him the story of the near miracle that morning. He was a highly rational young man with a family background steeped in scholarship. He looked at me for a while and asked quietly to be introduced to the young Burman still sitting passively outside my basha but. I took Roberts to him and after a quiet chat we strolled over to the crater where the phenomenon occurred. I had no film in my camera and Roberts did not possess one but we both agreed that a mere picture of the tree and crater would have no meaning. I had laid some emphasis on the manner in which the young man had seemed to be driven to start digging – almost a matter of inner compulsion. Talking it over we were both agreed that there was little point in taking the matter beyond the factual happenings. This we agreed, was the stuff life was made of.

One of the matters we talked about, at lunch time, concerned the two options which had emerged during my talk with the Agent and I asked him if Mr. Hutchings had spoken to him about it.

Evidently there had been no time since the Agent had been driven straight up to Dimapur without even a short halt at Imphal. We mulled over the issue for a while till realisation dawned upon us that the matter was no longer in our hands; the previous day’s bombing had settled the issue by driving the refugees back on to the road to Dimapur in ever increasing numbers starting from that morning.

As if on cue, a DR arrived with a cryptic message from one of the out-lying camps that it had almost been emptied of refugees within the matter of an hour as a result of a rumour that a second Japanese attack was imminent – either that afternoon or the next morning. I had experienced this situation earlier in Mandalay and knew that there was little one could do to stop the rot for the simple reason that neither we nor the Army were in a position to deny the possibility on any rational basis. All we could do was to intervene before things went much further and the ‘disease’ spread to the other camps as well.

The essential thing was to keep the road open and the Army readily agreed to put some of their trucks on the road to pick up as many refugees as feasible and drop them at Dimapur before the day’s end. The Army again did a splendid job and that evening the DC and I went round to all the Camps around Imphal to talk to the refugees and inform then that with low monsoon clouds over the whole of Burma it was unlikely that the Japanese would mount another attack just them. However, the Army convoys moving up to Dimapur would carry as many refugees as they could so there was no need for panic evacuation of the camps, in fact, we would keep them informed of the situation as it developed and arrange regular evacuation by Army convoys on a daily basis.

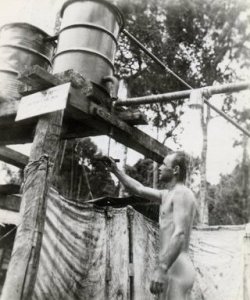

The daily showers were also beginning to make conditions difficult in the Camp.

Leaky roofs overhead and soggy ground conditions underfoot made life somewhat trying even for these refugees accustomed to the dampness of the Burmese monsoon. The growing influx of refugees had imposed tremendous pressure on the relatively meagre supplies of essential commodities including firewood, available in the Imphal market and though the Camps provided rice and salt in adequate quantity to each refugee family, there was obviously a need to supplement it with whatever else could be procured in the shape of lentils, vegetables and eggs but firewood remained the most important single commodity. Its non availability could create a serious problem as we discovered one evening when we came across a ‘gang’ of refugees pulling down some temporarily vacant ‘bashas’ for fuel leading to serious fights and quarrels. This was no time for half measures. We straightaway called the local wood contractor and arranged to set up a special fuel dump solely for refugees in one of the more centrally located camps at a rate to be fixed by the DC. He moved fast and we were astonished to find the fuel-wood depot at the designated camp in full operation the next morning.

These remained our major concerns on an hour-to-hour basis from morning till late at night we were both fully aware that with this large population of refugees living under a pall of tension, it would not take much to spark off a major ‘law and order’ situation literally on the drop of a coin. I was beginning to realise that I could not possibly leave Imphal before the refugees had been cleared from the town.