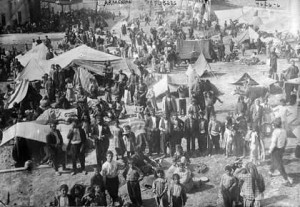

Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18 – 16

Aroundthe end of October 1918, when it was clear that Germany and its allies were facing defeat, the hospital in Ras al-‘Ain was abandoned by the German doctors who had been running it. The Indian POWs and Armenian refugees were left to subsist on the hospital’s remaining stores of food. (p.191)

British and Indian troops were known to be advancing northwards but there was still no sign of them. This created great confusion.

‘We run into our Armenian colleagues every day,’ writes Sisir. ‘They’re in despair. But what can we do for them? If the British arrive soon, they’ll be safe.’ (p.193)

At the beginning of November 1918, Sisir writes: ‘I’m overjoyed at the thought of going back home, but in the midst of that I am despondent at the thought of the [Armenian] mohajers and their fate. We’ve worked together for so many days; we’ve shared sorrow and joy.

They have become like our own. I wonder, even if the Turks don’t kill them, what will they find when they get home? Who will they return to? Who knows if they even have any homes left!’ (p.194)

On November 17th, all of a sudden, the POWs were informed that a train would come for them that night. Sisir and his companions went to the station well ahead of time because they were concerned about finding a covered wagon. Sisir explains that this was because Turkish trains ran on firewood, there being a shortage of coal in the country: the engines couldn’t work up much steam: ‘At the slightest incline the engine would wheeze as if it had run out breath, and flames would shoot out of the chimney burning everything nearby.’ (p.198)

This was a hazard in an open wagon, because cinders and flames would be blown back, and would often cause fires.

Sisir recounts that he was once traveling in an open wagon, with one of the Bengal Ambulance Corps’ camp followers, a sweeper by the name of Jumman. A flaming cinder happened to fall on Jumman’s turban and flames shot up from it. Between the two of them they managed to put out the fire, but Jumman said afterwards, ‘lucky that I’m not a Sikh or my hair would have been burnt.’