Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18 – 12.

The Indian POWs who were being treated at the Central Hospital in Aleppo, in 1916, discovered soon enough that they had many commonalities with their erstwhile ‘enemies’ – that is to say, the Turkish soldiers who were also being treated there. ‘We would talk,’ Sisir Sarbadhikari writes in his memoir Abhi Le Baghdad, ‘about our countries and about our own joys and sorrows. If we said that we have this or that in our country but you don’t have it here, they would say how can things improve in our country? All we do is fight, and that too with big and powerful countries. If you go into our country you’ll see, even the fields are lying fallow. Who’s to do the work? Everyone’s away fighting; only the women are at home.’ (p.158)

‘One thing they always said was this: What are you going to gain from this war? Why are we cutting each other’s throats?

You live in Hindustan, we live in Turkey, neither of us have ever met, we have no quarrel with each other, but at the behest of a couple of men we’ve become enemies overnight.’ Sisir pauses to ask: ‘Is this what’s in the heart of every soldier, in every country, at all times?’ (p.158)

Then he continues: ‘There was a man from Edirna-le or Adrianopolis who used to say, how will things improve? Sultan Abdul Hamid put a curse on our heads because of which we’ll have to be at war for a hundred years.Why he put such a curse on us I cannot say kardesh.’ (p.159)

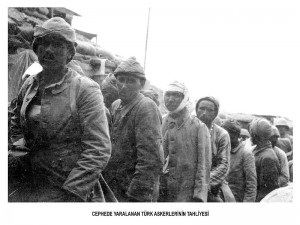

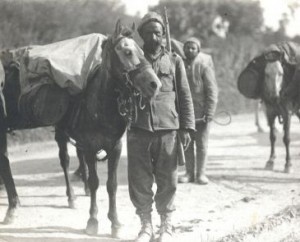

Sisir tells some touching stories about his kardeshes. For example: ‘An old Turkish soldier came to our ward to collect cigarette butts. He was bent over with age, but he happened to look up and he caught sight of a young Turk in one of the beds.

He gave a shout and then we saw that they were hugging each other with tears rolling down their faces. After they had calmed down a bit we learnt that they were father and son; for three years they had had no news of each other – and today this sudden meeting! … In Turkey this kind of thing is not unusual – fathers don’t hear from their sons; the sons don’t know where their fathers are; householders go off to fight and don’t know what’s going on at home. They get news when they go back, or when others from their area return from leave.’ (p.155)

He follows this with a story that graphically illustrates the conditions of soldiering at that time: ‘There was a Turkish soldier in our ward, about thirty years of age, he had been wounded in the fighting.

With him was a pretty young girl, of about five or six. Her name was Farida. She used to play with all of us. The soldier had no one at home to leave his daughter with, so he took her with him when he went to fight – he brought her to the hospital too.

During the fighting he would leave her in some safe place in the care of one of his comrades… (One day) I asked him: Kardesh, if you had been killed in the fighting what would have happened to your daughter? He smiled and said ‘Allah bilior’ – or ‘only Allah knows’… I never saw this kardesh looking gloomy. And the girl? She was always cheerful, busy playing.’ (pp. 155-6)