Shared Sorrows: Indians and Armenians in the prison camps of Ras al-‘Ain, 1916-18 – 4

In the first few months of the campaign, the British-Indian forces met with little resistance from the Ottoman army. The going was so smooth that the campaign was decribed as a ‘river picnic’.

But just south of Baghdad, at the ancient town of Ctesiphon,

General Townshend’s army ran into a large and well-entrenched Ottoman force. The British advance was blocked and the 6th Army was driven back to a small town called Kut al-Amara.

There, with just one month’s foodstocks in store,

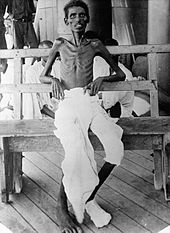

the British-Indian force endured a siege of five months, at appalling cost.

Many soldiers died of hunger and disease

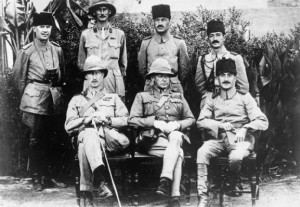

before General Townshend surrendered to Khalil Pasha, the Ottoman commander on April 29th , 1916.[i]

At the time this was thought to be the greatest defeat that the British had ever suffered in Asia.

On May 12 1916 Sisir Sarbadhikari

and the other prisoners of war were sent to Baghdad on a steamer.

Sisir remained there for a couple of months, and then,

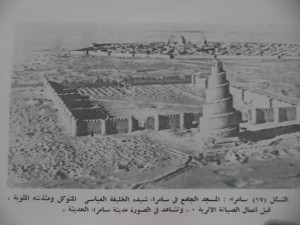

on July 19th he and some other prisoners were dispatched to Samarra, about 60 miles away, by train.

Then began a series of grueling marches, in the burning heat of the Mesopotamian summer: the prisoners were driven brutally northwards through inhospitable country with very little food and water. British accounts of the march speak of floggings, starvation and terrible cruelties: ‘troops (British or Indian) falling out of the line of march from sheer exhaustion were left to perish either of starvation or the probability of being murdered by the Arabs.’ [ii]

Cruelty and hardship figure in Sisir’s narrative too, but his tone is stoic, almost dispassionate, and he often pauses to reflect on history and comment on the beauty of the countryside. Of the horrors of the march, the recollection that was to remain most sharply etched into his memory was of the shouts with which the guards would wake the prisoners in the small hours of the night. (121)

In twenty-five days the prisoners marched from Samarra to to Mosul, by way of Tikrit, Sargat and Hammam Ali. It was after leaving Mosul that they began to see signs of the devastation that had been visited upon the Armenians of this region.

_________________________________________________

[i] The precise numbers remain undetermined but it is estimated that about 3,000 British and 10,000 Indian soldiers went into captivity after the surrender. Cf Heather Jones: Imperial Captivities: Colonial Prisoners of War in Germany and the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1918, in Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, CUP, 2011.