When we think of the technology of movable-type print it is always in a spirit of gratitude, which is only as it should be. Yet, for all its blessings, print was also responsible for deepening the divide between words and images.

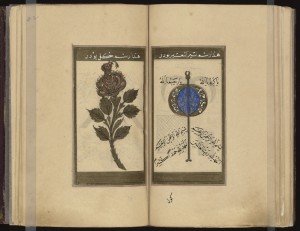

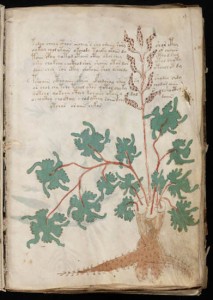

Before the invention of print words and images had usually been closely joined,

no matter whether in paper or papyrus, parchment or bark. Illuminated manuscripts joined letters and images so that each added to the other.

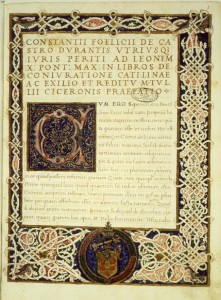

Such was the effectiveness of this that even after the invention of print, great efforts were made to recreate the look of earlier forms of the book. Not only did typefaces mimic calligraphy,

but many books continued to be illuminated by hand.

But hand-painted books were hugely expensive: ‘plates’ quickly became the printed book’s principal means of reproducing images. But the possibilities of the plate were also governed by considerations of cost, and this meant that one of the most vital characteristics of the image – colour – was quickly leached out of it.

Printing came of age in a Europe that was convulsed by puritanical fervour and iconoclastic zealotry:

a strain of hostility towards images was perhaps a part of its genetic make-up.

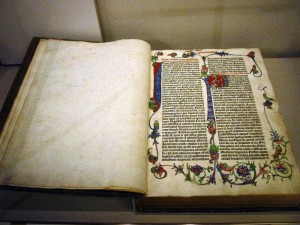

The Gutenberg Bible, printed in the 1450s,

was ornamented with richly coloured floral imagery;

but a century later, the Geneva Bible – ‘the Bible of the Puritans and Pilgrims‘ and Shakespeare –

featured neither colour nor imagery of any kind.

But despite that, for several centuries the image continued to command a place of respect in print. Even until the early 20th century the inclusion of plates was considered to be a virtue in a book. It was the mass-produced book that upended the criteria by which books had hitherto been judged. Affordability became the new index of a book’s appeal: everything that added to production costs came to be regarded as extravagant and unnecessary, even frivolous. This confirmed the prejudices of textual puritans who had long looked askance upon the admixture of images and text. By the mid-twentieth century the triumph of the text was complete.

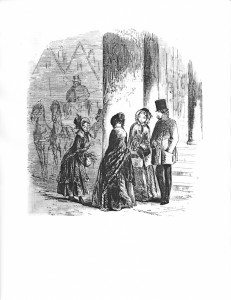

For Dickens,

it was normal for pictures to be included in a novel; for Joyce or Hemingway this would have been inconceivable.

‘Art’ and ‘Literature’ went their separate ways and all traffic between the two came to be seen as damaging. This relationship is perfectly summed up by the print media’s preferred word for images: illustration.

How very different are the connotations of the words

‘illuminate’ and ‘illumination’!

It is sobering to reflect on how these prejudices came to be absorbed by cultures around the world, and how powerfully they influenced ideas of knowledge and education. When I was a boy comic books were regarded as an indulgence that prevented the mind from developing fully. You could be punished for reading them. The thinking was that a mind that became accustomed to the figurative would be less able to cope with difficult or abstract ideas.

But why should this be the case?

Don’t mathematicians rely on symbols and figures?

Don’t the pictures of Caravaggio, or the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat,

have to be ‘read’ in ways that require a great deal of thought?

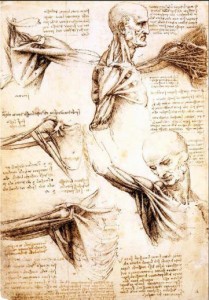

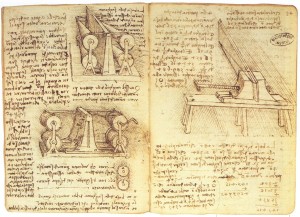

When we look at these pages

from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks it becomes evident

that for him text and imagery formed a single mode of thought.

Enjoyed reading this.

In episode 1 of the currently running BBC adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s novels about Thomas Cromwell (“Wolf Hall”), he is shown ( in the late 1520s?) with a beautifully illuminated book, William Tyndale’ s English translation of the New Testament, which he seems to have secretly acquired (possibly via a German merchant in the “Steelyard” district of the City of London?)

Would this have been likely to have been an illustrated/illuminated version of a printed book (c.f. The much earlier “Gutenberg Latin Bible from the previous century) and would it be likely to have been a “bespoke” copy (secretly) specially commissioned from Worms (?) by Thomas Cromwell, do you think? (c.f. the coloured copy of Tyndale’s NT in the British Library)

Ian Goodacre

email:

mail@goodacrehome.plus. com