On Nov 17 this year, the Burmese writer Ma Thida and I went to visit the offices of the Press Scrutiny Board in Yangon, the seat of the country’s once-feared censorship authority.

I was curious about the building because I had heard so much about it from Burmese writers,

including Ma Thida who has endured some terrible moments there.

She has spent many years in jail because of her writings, and her memoir of her prison experiences has just been published in Burmese (she is now collaborating on an English translation).

Ma Thida’s publisher, San Mon Aung, drove us to the Board’s office building.

Nobody stopped us or asked any questions as we drove up to the building.

At the entrance we ran into a team of journalists from al-Jazeera –

they too were touring the building, filming and interviewing people as they pleased.

Inside, many rooms were empty,

and the few censors who remained seemed embarrassed to be found doing whatever they were doing.

At the end of our visit a newly-appointed member of the Board, Myo Myint Maung, came running down to meet us –

I was told that he is himself a celebrated young poet (the censors of the past were junior army officers).

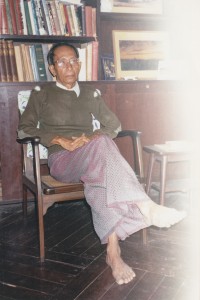

While walking around the building I recalled a meeting with one of Burma’s most revered 20th century writers:

the late Saya Mya Than Tint.

A friend of mine, U Tin Maung Than, a magazine editor, had taken me to his house in Yangon in 1996. When I was introduced Saya Mya Than Tint said: ‘I know your name – I’ve read something of yours.’

I was astonished. In those days Myanmar’s censorship regime was so draconian that very few foreign books or magazines percolated into the country: they were routinely confiscated at the airport. I found it hard to believe that something of mine had succeeded in slipping through the censors’ dragnet.

But Saya Mya Than Tint was sure of it. He told me to wait and went to his study. A few minutes later he came back with a copy of a magazine (I think it was an issue of Granta). Inside was an article that I had written.

I was dumbstruck. ‘Where did you get that?’ I said. ‘How did it get past the censors?’

He told me the story: in Yangon, as in India, there are many rubbish-buyers who go around the city buying up discarded household goods, including books and paper. Saya Mya Than Tint had befriended the buyers who serviced the city’s diplomats, some of whom received books and magazines through embassy couriers. In this way he had ensured that he always had a steady supply of foreign books and magazines!

Saya Mya Than Tint was then 67. He had been imprisoned for nine years under the Ne Win regime. Some of those years were spent on the infamous Coco Islands, where prisoners were made to forage for their food. Yet his intellectual hunger, and his thirst for books, remained undiminished – if anything they had been enhanced by his experiences. He took immense pride in staying abreast of what was being said, thought and published around the world.

When it was time for me to leave, Saya Mya Than Tint gave me the manuscript of a forthcoming English translation of one of his books: a series of vignettes, based on random encounters, it was then called Tales of Ordinary People. It was later published in English under the title On the Road to Mandalay. It is a deeply humane, revelatory book and everyone who is planning to travel to Burma should put it at the top of their reading list.

Saya Mya Than Tint died two years after my meeting with him. My encounter with him was to leave a lasting impression, not least because of his insights into the minds of censors. I often recall one of his observations: repression, he said, establishes a bizarrely paradoxical relationship between censorship and fantasy; the censor becomes the true fantasist; the writer becomes the realist. ‘In an authoritarian culture,’ he said, ‘people lead two-track lives. Intelligence is gathered constantly, everything is known, yet the rulers use their information only to produce lies. It is like log-rolling: one lie makes another lie and it goes on like that until everything is make-believe. The rulers retreat into a world of illusion where they cannot see reality.’

Even in Burma, where so many writers have suffered terribly at the hands of the junta’s censors, few endured such appalling privations as Saya Mya Than Tint. Yet, what was most instructive to me about his attitude towards the censors was that he did not see himself as a mere victim in relation to them. He saw the relationship between writers and the regime as a contest, a struggle in which the censors did not necessarily have the upper hand. Words are, after, all the battleground on which the war is waged, and the lay of this land favours the writer, not the censor. On this territory writers can always find ways of eluding their adversaries.

During our meeting Saya Mya Than Tint talked at great length about one of the strategies that Burma’s writers used to outflank the censors: it drew upon a custom with a long history. In the past the kings of Myanmar used to pay homage to writers and scholars on a certain day of the year. In modern times, this ‘day’ has come to be stretched into a period of several weeks, during which writers and artists make public appearances around the country, delivering talks and holding recitations and readings. These gatherings are organised locally, and funded by public contribution. The tradition is so deeply-rooted that the military regime was never able suppress it outright, although it did ban literary meetings from time to time. The writers and artists who spoke on these occasions were careful to avoid explicit mention of politics; they discussed political matters only through allusion, oblique references, satire and humor. ‘Because we are allowed to say so little in plain language,’ said Saya Mya Than Tint. ‘We have to find secret languages with which to communicate with our audience. And even though we never speak directly about the situation, the listeners understand exactly what we mean.’

It is certainly a fact that in spite of the terrible risks, Myanmar’s writers resisted the censors with astonishing fortitude and courage. Many defied the regime openly, disregarding the threat of jail sentences:

to this day people talk with awe of the intransigence of the legendary writer Luda Daw Amar (mother of Saya Ni Pu Lay and co-founder, with her husband, Ludu U Hla, of the hugely influential Ludu Press in Mandalay).

Other writers used Burma’s cultural traditions in resourceful ways to keep political debate alive. As a result, the ruling junta was never able to put a stop to political discussion, despite all its efforts. In the end, it was the infinite cunning of language itself that was the censor’s most potent adversary. Myanmar’s experience in that period is proof that the greatest enemy of the absolutist state is the complexity and inventiveness of the human imagination.

Now that those days are gone – forever, I hope – and Burma is suddenly the focus of the world’s attention, I find it saddening that the talk about the country is so much focused on politics, money and power rivalries. Myanmar’s writers, and all that they did to keep their compatriots’ spirits alive seem hardly to figure in the story, at least in the manner of its telling in the international media.

Would it be possible to speak of the end of the Soviet Union without mentioning Solzhenitsyn? Can we think of the fall of the Iron Curtain without thinking of Milan Kundera and a host of other writers?

The writers of Myanmar played just as significant a part in bringing about the changes that are now sweeping the country as their counterparts did in Eastern Europe and Russia. That this is so little recognized says a great deal about the world’s vision of culture in Asia.

Loved reading it. Afterwards we often tend to forget or fail to understand how terrible those days were, though in Myanmar, it is still too recent to be forgotten!