On November 14 this year, I returned to Burma/Myanmar after 15 years. During my time there I thought often of the opening sentence of L.P.Hartley’s novel The Go-Between: The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

I had last visited Burma in 1997 and the trip did not end pleasantly.

I had interviewed Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who was then under house arrest,

at her home on Yangon’s University Avenue.

This had brought me to the attention of the secret police, who followed everywhere from the moment I stepped out of the house. My greatest concern was for my notes and tapes, which I thought might be confiscated when I went to catch my flight out of the country, so I enlisted the help of a friendly diplomat who was kind enough to stay with me until I boarded the plane.

This had brought me to the attention of the secret police, who followed everywhere from the moment I stepped out of the house. My greatest concern was for my notes and tapes, which I thought might be confiscated when I went to catch my flight out of the country, so I enlisted the help of a friendly diplomat who was kind enough to stay with me until I boarded the plane.

A few months later my article, At Large in Burma, appeared in The New Yorker. After that it became public knowledge that I had done something that was perhaps even more offensive to the junta than interviewing Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. I had spent time on the Burma-Thai border,

with rebel students of the ’88 movement and a troop of armed insurgents, the Karenni, who were one of the many ethnic groups that were then fighting the Burmese army.

In the years that followed I did not bother to apply for a visa again. Even if it were granted I knew that I would be watched if I went to Burma. This meant that my friends and acquaintances might get into trouble if I tried to contact them. I could see little point in visiting the country if I could not meet the people I knew.

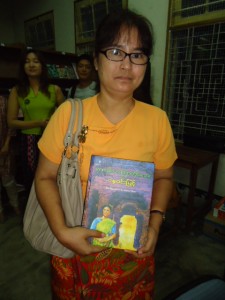

In the meantime, my novel The Glass Palace was published and in the succeeding years I heard that it had found many readers in Burma. In 2009, I learnt to my great surprise that the novel was actually being serialised, in translation, in a popular Yangon magazine, Shwe Amyutay, with illustrations by the artist Wa Thone. In August 2010, the novelist Robert Coover, organized a series of Burma-related events at Brown University, to which he invited the writer Ma Thida, and the publisher of Shwe Amyutay, Saya Myo Myint Nyein, and the translator of The Glass Palace, Saya Nay Win Myint .

It was in talking to them that I understood that Burma was changing rapidly under President Thein Sein.

I had of course heard that the regime had been easing up a little of late – but similar rumours had circulated many times before, and I had assumed that the changes would be largely cosmetic.

But after talking to Ma Thida, U and Saya Ne Win Myint I understood that something genuinely momentous was under way in Burma.

Then, earlier this year, I learnt that Saya Ne Win Myint’s translation of The Glass Palace had been awarded the Myanmar National Literature prize (see my post of February 25, 2012).

This was extraordinarily meaningful to me and it made me eager to return to Burma.

So on Nov 14 there I was again, at Yangon’s Mingaladon airport, on that same patch of tarmac that I had last crossed fifteen years before. And within moments of arriving it became clear that I had come to a different country.

What is this new country to be called, ‘Burma’ or ‘Myanmar’? In the past I had generally used the former, following Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s preferred usage. But it is now my feeling that the two names should be used interchangeably. This is my practice also in other instances of renaming – for example, with the city of my birth, Calcutta/Kolkata. In conversation, as in writing, I sometimes say ‘Calcutta’ and sometimes ‘Kolkata’. I did this even before the city’s official name was changed, and I don’t see any reason to alter that practice. After all most places have multiple names, and it makes sense that the official usage should sometimes change, to reflect political and cultural developments. But this does not mean that other names should be expunged from memory – on the contrary, I feel they should be actively recalled. As far as I am concerned the more names (and words) that there are in circulation, the better it is all around.

The new Burma abounded with signs of change – but the moment when the difference between the Myanmar I had known, and the country I had landed in, became most starkly apparent to me was when I visited the offices of the Press Scrutiny Board, the seat of the country’s censorship authority.

The mere fact that I could writed that the last sentence is itself an indication of the significance of the changes that are currently under way in Burma. Fifteen years ago I would no more have conceived of entering that office than I would have thought of breaking into Burma’s most notorious prison, the jail at Insein. The censor’s office was then a place of dread: people’s voices shook with fear when they spoke of it.

At that time the ruling military junta was known as SLORC – surely the most expressive acronym since Ian Fleming’s SMERSH ? – and the Press Scrutiny Board was the instrument through which it controlled the country’s media and publishing houses. The Board wasn’t the junta’s invention however – like many of Burma’s institutions of repression it was established by the British during the Second World War. But in the course of its evolution the Board had brought into being a regime of censorship that was, in a primitive and brutal way, one of the most intrusive and repressive programs ever devised to control thought and expression.

Under SLORC and its successors every word that was printed in Myanmar (or not, as the case may be) had to be filtered through the offices of the Press Scrutiny Board: twice in the case of journals and magazines; three times for books. Those who ran afoul of the censors were often sentenced without appeal: nowhere in the world were writers consigned to jail as frequently or with as little cause as in Myanmar. Many of Myanmar’s best-known contemporary writers, such as Ni Pu Lay, Nu Nu Yi and Ma Thida spent years in prison.

Politics was not the only forbidden subject for Burmese writers; the censors prohibited them from mentioning any aspect of life that could be interpreted as ‘negative’ – poverty, illness, corruption, destitution. So broadly were these rubrics interpreted that anything at all could be banned at the censors’ will. Stories about suicide, for example, were strictly prohibited, as were references to moonlighting, or the high price of medicines – or indeed, any of the minor difficulties of everyday life. But the censors’ decrees did not stop at content; they extended to literary form and even grammar. A well-known modernist writer who tried to experiment with the placement of verbs in his sentences once found himself denounced for ‘abusing the Burmese language’.

The subject to which the censors were most sensitive, was of course, that of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

U Tin Maung Than, a well-known Burmese writer and former editor of a Rangoon literary magazine told me this story fifteen years ago: once, at a loss for a inoffensive cover design, he had picked a picture that seemed to him to have no connection whatever with present day Burma: it was a photograph taken on the other side of the world and featured a penguin on an ice-floe.

But even this was banned – the solitude of the penguin was interpreted by the censors as an oblique reference to the plight of Aung San Suu Kyi.

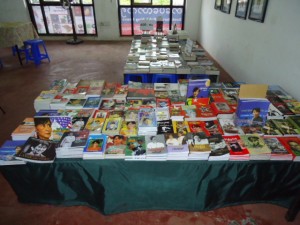

(Today bookshops have entire sections devoted to Aung San Suu Kyi.)

On my earlier visits I had discussed the Press Scrutiny Board at great length with Yangon’s writers, editors and publishers. Their stories haunted me: I became fascinated with the workings, as it were, of the censorial mind. It seemed to me that the concerns of the Press Scrutiny Board revealed a great deal about institutions that seek to control the thoughts and words of others (and of course, such institutions exist everywhere, in different guises).

My publisher friend, U Tin Maung Than, had spent many nerve-racking hours with the censors, waiting for them to pass judgement on the proofs of his magazine. One day, in January 1997, I persuaded him to point out the building where he and his colleagues endured these ordeals.

At considerable danger to himself he led me past the gates of the Press Scrutiny Board’s office building, and I surreptitiously took this picture.

It was only very recently that the censors were unseated. In August this year, on the heels of many other dramatic changes, came the announcement that private publications would no longer be censored: .

But the Press Scrutiny Board still exists, and is still housed in the same building, although it now performs only a few routine functions. When I learnt that it was now possible for visitors to look around the building, I knew at once that I would have to go.

Dear Amitav! It is nice to read from you. Not only the Glasspalace sequences, which bring us to Burma in its harder times but also this account written above are great t read. The most interesting thing perhaps is to be an eye witness to a country or region in a rapid social change which always follows the political change after years of drought. I have the same experiences for the East Germany context, which in terms of music and art had its most intense times after the break of the wall in the early 1990ies. The same for Soviet Union/ Uzbekistan, where I apparently came already a little late with my forst visit in 1994. I really eny your possebilites to be there in Burma now and then….